Heading G20 will give India a foreign affairs year like it has never had in history.

You can trust Narendra Modi to exploit this to India's benefit.

And, of course, to his own in his election year, explains Shekhar Gupta.

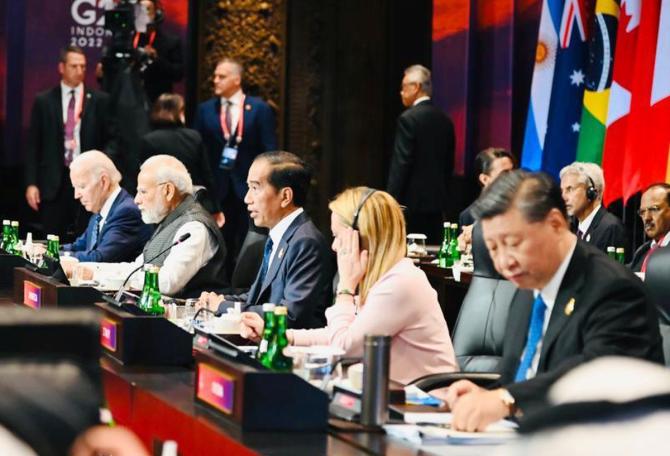

Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi at the G20 Summit in Bali, November 15, 2022. Photograph: Mast Irham/Pool/Reuters

The big G-20 summit in Bali that made more headlines with what happened on its sidelines -- like that Trudeau-Xi encounter -- is over.

The baton has passed from Indonesia's Joko Widodo to India's Narendra Modi. It sets the stage for a never-before foreign affairs year for India.

Especially as India will be hosting so much of the world -- accounting for 80 per cent of global GDP and 75 per cent of world trade -- under a leader who so revels in grand spectacle.

L K Advani spoke brave words once, calling Mr Modi a good event manager, and has been paying for it since.

Every birthday of his becomes an event only when Mr Modi arrives and cameras find that one visual they want.

This year-long spectacle will be no ordinary event. It will set up Mr Modi's 2024 campaign brilliantly for him.

It will bring the most prominent faces from the world to India, they will all perforce be heaping high praise on its leader.

During the year, nearly a hundred meetings will be held, culminating in a summit.

Meetings will be taken to cities across the country. There will be much hugging, laughter and the glitziest packing of the 'Vishwaguru'.

This so neatly dovetails into the general election campaign that it will be tempting to dismiss it as another tamasha mostly directed at domestic politics.

There are many good reasons, however, why we should avoid that temptation, take off our political goggles and put them away for a bit.

We might then be able to appreciate how vital a foreign and strategic affairs opportunity this is for India.

Three decades after the vaporisation of the Soviet empire created a couple of years of instability in the global balance of power, another such flux has arrived thanks largely to Vladimir Putin but partly also to Xi Jinping.

The post-Soviet world settled into a new unipolar arrangement that lasted a quarter of a century. Until a rising China began to challenge it.

This change was helped along by the notion of declining American power.

First with Barack Obama's idea of 'leading from behind', then with Donald Trump's retreat from globalisation, and finally the humiliating Biden withdrawal from Afghanistan.

If the world had remained frozen like this, as it was, say, until the beginning of 2022, this G-20 wouldn't have had a fraction of the oomph it has today. Let's list some dramatic changes:

*Far from continuing to decline, American power has made a turnaround. It is rising again.

Its economy, although beset with inflation and other challenges, is healthier than the rest of the developed world's and is recovering.

Its often-bumbling leader has turned in a surprising (for friend or foe) performance in midterm elections. And just a year after losing out a war of tribal insurgency to the Taliban, it is winning a real one.

In Ukraine, and in this case, the enemy is a former superpower that is also the most valuable ally of the aspiring new superpower, China.

Most importantly, it's winning without having to employ any military personnel directly.

Which might indeed be the reason it is winning. See the history of America's, or any bigger power's wars overseas.

It loses when it sends its troops to fight someone else's wars. Vietnam, Iraq, elsewhere in the Middle East and Afghanistan the second time.

Closer home, India lost to mere armed irregulars in Sri Lanka. But America won the first time in Afghanistan because the natives were fighting, as is the situation in Ukraine.

You are on the winning side when the people you are backing are willing to fight for their nations.

Which is precisely why India liberated Bangladesh in 13 days.

For Joe Biden and the US, Volodymyr Zelensky's Ukrainians have erased the blot of Kabul, if by employing weaponry gifted by the Western power.

Russia is losing militarily, diplomatically and politically.

I am sobered by the vast popular support for Mr Putin in India and the deep, residual nostalgia for the Soviet Union which translates into a self-created mythology that Russia is just the new name of old USSR, the virtuous side in the contest.

But hard luck if, after nine months of fighting, your side is retreating on an entire 800-km front, against an enemy a fraction your size. Your side is losing.

Whatever the internal politics in Moscow, this will leave a much weaker Russia and Putin.

It will be good for India. Because like Russia becoming a China ally and flirting with Pakistan, India has also been widening its strategic choices.

A systematic decoupling started on armaments some five years ago and is now irreversible, albeit slow, given the vast arsenal of legacy systems.

We in India tend to plonk ourselves philosophically and -- funnily -- also morally on the losing side in distant wars where we have zero leverage or ability to influence the outcome.

In the first Afghan jihad, we wanted the Soviets to win, but they lost.

In the second, we were cheering for the Americans and they were defeated.

Now, in the more vocal public opinion, media, foreign policy commentariat and strategic community, there is this touching belief that the Russians are unbeatable.

Of course, they haven't used their best weapons. Of course, they will eventually win. Here's the truth: We will end up on the losing side again.

While the immediate risk to us is that we will look silly, the Chinese see it differently.

Mr Putin's blunder has dealt a body blow to China's rising power. It needed Russia as an ally and a permanent source of cheap energy.

A weakening Russia caught in a losing war punctures China's balloon.

To begin with, it's a huge blow to the Belt and Road Initiative. With repeated nuclear threats now, it is also an embarrassment.

Look at it like this. All three of China's closest strategic allies, North Korea, Pakistan and Russia, are the only nations in the world that like flaunting nuclear threats. There is great revulsion for this everywhere else.

Until about five years ago, conventional wisdom was that a rising China would overtake a declining America by 2030. This has failed the test of time.

It is today China that's struggling for growth.

Its working age population is declining, growth stalling, debt burden is at crippling levels and the big tech/fintech sector in a crisis.

It is worsened by the fact that Xi Jinping has gone systematically after its biggest tech-finance success stories mostly to consolidate his own total power if not out of envy of their superstar founders.

He's brought back emphasis on State-owned enterprises or what we might call as public-sector units in India. These are steps backwards.

Until recently, so many experts were saying that China's GDP would surpass that of the US by the end of this decade.

Now they are hiding or searching for excuses as new calculations show this not happening until 2060. Likely, never.

It's forcing the rest of the world to diversify their supply chains, decouple from China.

A desperate warning on this was a part of Mr Xi's sermon to Mr Biden in Bali as revealed in the Chinese foreign ministry readout. But he can be sure that nobody would listen.

His arrogance has damaged the China story.

Maybe not as badly as Mr Putin ruined Russia's, but then he had an enormously bigger Gross National Power to play with.

To say that China is weakening will be an overstatement. But that it isn't strengthening any more, is enough to change the global balance of power.

If this set of changes drives the G-20 year when India is in the chair, it is a lot of newly-opened strategic space for Narendra Modi to play in.

He's so far handled this deftly, balancing India's economic and strategic interests, playing US and Russia and keeping China off his back.

You can trust him to exploit this year-long opening to India's benefit. And, of course, to his own in his election year. You can't grudge a politician that.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025