'If enough people defy the law and insist on flouting fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution in the name of religion and custom, does that endow a bigoted, unjust demand with merit?', asks Shuma Raha.

Social justice and progressive social reforms are never a walk in the park.

They are hard-fought battles because they go against the grain -- against orthodoxy, dogma, prejudice and discrimination.

A civilised society is one that sets up institutions, which, if need be, can bring about these changes through legal fiats in line with the principles which are supposed to govern that society.

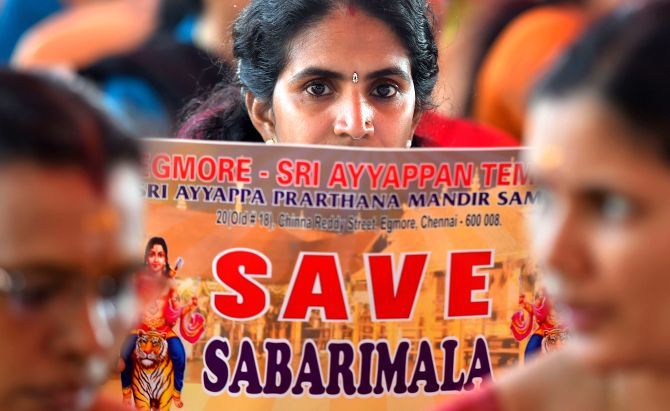

Last year, India's Supreme Court, an institution which has delivered many wise and progressive judgments, came out with another landmark ruling: It lifted the ban on the entry of women between ages 10 and 50 into Kerala's Sabarimala temple.

The court held the practice discriminatory and unconstitutional and said that women's right to equality before the law gave them the right to pray at the shrine of Lord Ayyappa.

That there would be virulent protests against the verdict was a given. That patriarchy and apologists for anti-women practices, which masquerade as sacred religious customs, would be out in force against it was expected.

That political parties would try to add fuel to fire to get maximum mileage out of the issue was no surprise.

Indeed, such has been the mob frenzy against the ruling that only two women have so far managed to enter the temple, leading to it being shut down at once for 'purification' rites.

Even so, Indians who put their faith in Article 14 of the Constitution that gives every citizen the right to equality and hence the right not to be discriminated against on the basis of religion, caste, gender, among others, had hoped that good sense would prevail and the protests would lose steam.

They had hoped that Sabarimala's drummer boys of misogyny and medievalism would have to stand down before the decree of the country's highest court.

But on Thursday, November 14, the Supreme Court itself dealt a blow to such a hope. By a 3-2 verdict, it agreed to hear a clutch of review petitions against its 2018 judgment and referred them to a larger bench of seven judges.

While the court did not stay the earlier verdict, the Sabarimala issue is once again split wide open.

What's more, by linking it to regressive practices in other religions, the matter has been complicated further.

Those who insist that they are privy to the will of Lord Ayyappa, those who seem to have made misogyny the cornerstone of their faith in the deity, are jubilant.

They are already smelling victory, or, at least, an indefinite impasse which will amount to the same thing.

Critics of the Sabarimala verdict had every right to file review petitions. That remedy is available to Indian citizens who are dissatisfied with a ruling by the top court.

However, it is up to the court to decide whether to admit or dismiss a review petition.

On the same day that it admitted the pleas against the Sabarimala verdict, the Supreme Court threw out the review petitions against its December 2018 judgment, rejecting a criminal probe into the Rafale jet deal. The petitions lacked merit, the court said.

Which brings us to the baffling question as to what merit the honourable judges found in the pleas to review its decision to allow women between 10 and 50 (potentially of menstruating age and hence deemed 'unclean') into Sabarimala.

If enough people defy the law and insist on flouting fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution in the name of religion and custom, does that endow a bigoted, unjust demand with merit?

There would have never been any social reforms if blind faith and custom were held inviolable.

Not the abolition of sati, not widow remarriage, not the education of girls, not the striking down of instant triple talaq... No matter when they were done -- in the 19th century or the 21st -- they were bitterly opposed at first. But we progressed because that which is right did not genuflect before that which is wrong.

In its verdict on the Sabarimala case last year, the Supreme Court said, 'Where a man can enter, a woman can also go. What applies to a man, applies to a woman.'

What possible review can there be of the essential rightness of this statement?

Or are we now entering an astonishing realm where it may be all right to perpetuate a wrong as long as you add a minor footnote that it is, in fact, wrong?

Shuma Raha is a columnist for Business Standard newspaper. @ShumaRaha