For successive governments the Election Commission remains a ‘holy cow’, where unhealthy precedents are allowed to be nurtured since Independence, says N Sathiya Moorthy.

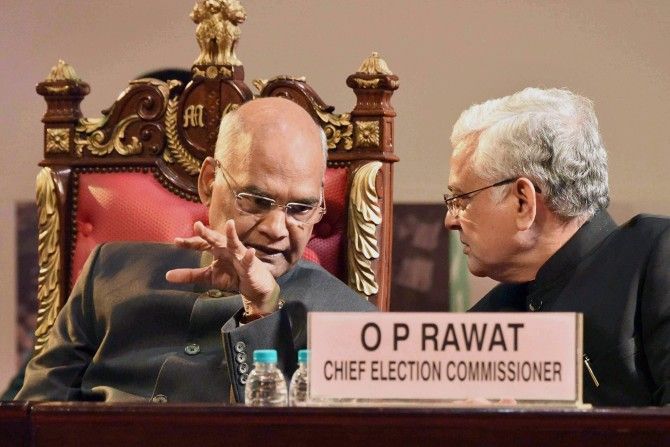

The appointment of Om Prakash Rawat as the chief election commissioner and another veteran civil servant, Ashok Lavasa, as election commissioner, has once again kick-started a muted discourse and animated accusations about the very process behind such appointments.

Stung by the disqualification of 20 of its MLAs, the Aam Aadmi Party has also turned the gun on the Election Commission.

As if this was not enough, Prime Minister Narendra Modi added a new dimension to all talks on electoral reforms by reviving an old suggestion for ‘simultaneous polls’ to Parliament and state assemblies, on the pleas of cost-cutting, time wastages and policy distractions.

He has since followed it up, asking his Bharatiya Janata Party chief ministers and others to kick-start a national debate on the subject. President Ram Nath Kovind too flagged the point in his ‘maiden address’ to Parliament, since.

Coming as it does from the incumbent government at the Centre, PM Modi’s suggestion needs to be debated on merit, and debated for merit, as there are minor aspects of electoral reforms that hit at the root of EC’s accountability and, more so, credibility. It relates to the very appointment of election commissioners and the chief election commissioner.

Truth be told, no party or leader wants to question the EC or the appointment or impartiality of commissioners in a nation where periodic elections in some state or the other has become the order of the day. The last time the EC and the government had a quarrel, Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao went on to expand the commission to make it a three-member affair from the existing one-member scheme since the nation became a Republic. Offended incumbent EC, T N Seshan, went to court, challenging this change, but even he did not contest the mode and norms of appointments per se, lest his appointment too would have been questioned, ab initio.

At a time when governments and prime ministers, especially incumbent Modi and immediate predecessor Manmohan Singh, were talking tall on ‘administrative reforms’ and also the possibilities of professionalising sector-wise administration of government departments and public corporations through the induction and/or elevation of domain experts and in-house technocrats, for successive governments the Election Commission alone remains a ‘holy cow’, where unhealthy precedents since Independence are allowed to be nurtured.

While the Election Commission is a constitutional body, with a permanent staffing pattern internally at higher levels, and massive part-time induction/diversion of public servants at all levels for election-time duties, starting with door-to-door enrolment of voters to the actual conduct of balloting, most Election Commissioners and Chief Election Commissioners have come invariably from the civil service. Of the 22 CECs (or one-man ECs before them) including incumbent Rawat, only three -- S P Sen Verma, R V S Peri Sastri and V S Remadevi – were/are not civil servants.

None of them have had much experience in Election Commission work, other than while serving as district magistrates/district collectors, or as the home secretary, among others, in their parent state. Invariably, accusations of ‘political appointments’ have flown thick and fast almost on every occasion. Neither the Janata Parivar (1977-80), nor the National Front (1989-90/91), or the later day United Front (1996-98), all of which swore to reform the nation’s administration, including electoral administration, did anything different from the ‘corrupt and corrupting influence’ of the Congress.

Two BJP prime ministers, Atal Bihari Vajpayee (1998-2004) and now Narendra Modi were happy talking reforms until coming to power, but have not followed up on their promises afterward -- when alone it matters.

The Election Commission is not the only institution that is crying for reforms at the very induction stage of the Election Commissioners and the elevation of one among them (thus far) as CEC. The Comptroller and Auditor-General is another constitutional office, which has a huge network of officials auditing the accounts of every paisa spent from the Consolidated Fund of India and the rest, and yet incumbents are all ad-hoc appointees, giving room for flexibility and possible partiality in the choice, accompanied by avoidable controversies. At least since the Bofors scam and HWD submarine deal expose by T N Chaturvedi, the CAG has been in the news more than ever. At present, the 2G scam has continued to keep the media and national focus on then CAG, Vinod Rai.

Thankfully, barring ex-telecom minister A Raja, no one has pointed an accusing finger at Rai. But Chaturvedi’s ‘political colours’ got ‘exposed’ when the Opposition BJP made him a Rajya Sabha member on retirement and the Vajpayee government elevated him further as the governor of Opposition-ruled Karnataka. Post-retirement, M S Gill went on to become a minister of state in UPA-I and II regimes of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Navin Chawla, another UPA appointee, first as EC and later CEC, set off a controversy even when he was in office.

While Seshan made the nation and the world sit up and take note of his reforming the election processes across the country, his quarrels with then Prime Minister Rao were equally well-known, though thankfully less remembered and even less frequently recalled in comparison to the good work he had done/initiated. He blotted his copy-book even more by first contesting the presidential polls, and later against the BJP’s L K Advani from Gandhinagar Lok Sabha constituency in Gujarat -- and on a Congress party ticket.

The democratic dictum, ‘Caesar’s wife should be above suspicion’, does not seem to apply to political parties, leaders and governments at the Centre. Coming at a time when the government is tied down in a never-ending battle with the judiciary over the appointment of judges, questions about the need for ‘reformation’ in one unaffected area of democratic governance while the executive wants to bring others under its ‘control’, smacks of controversy and worse.

When state governments are being blamed for ‘over-politicising’ their State Election Commissions, created under the Constitution 74th and 75th Amendments pertaining to panchayati raj, the Centre alone does not seem to want to either create an independent mechanism, or accommodate the existing EC structure in the choice of election commissioners and chief election commissioners.

A concept has thus allowed to germinate and fester that all that is done by the Union is right and correct, and whatever initiatives taken by state governments (especially those run by ‘Opposition’ parties to the one in power at the Centre) cannot be anything but wrong, improper and inadequate. Such an approach, which is coming to pervade other areas of governmental policy-making, including education and healthcare, for instance, intelligence-sharing and terrorism investigation, all have a tendency to weaken the nation’s democratic structure, and thus the much-maligned ‘unity in diversity’ of the Indian nation and State, which has remained the bedrock of our national and nation-State experiment and experience.

It is another interesting aspect of Indian democracy that whenever a single political leader is seen to stand taller than all the rest put together, his party starts talking about a ‘presidential form’ of government through ‘direct elections’. The Emergency era options that the ruling Congress explored for Indira Gandhi’s permanency in power are too well known for repetition.

When Vajpayee was in power, the BJP was talking about the ‘presidential form of governance’. Now, PM Modi, possibly seeking to cover up for the inadequacies of his regional satraps and their ability to deliver at Election 2019, even when the political Opposition continues to be weak and divided, is talking about simultaneous polls, which means the BJP-NDA could continue to count on his personal popularity to win assembly polls, without having to fight another poll battle of the nerve-racking ‘Gujarat kind’ in every other state, whether his BJP is in power there or not.

Likewise, it is yet another irony of Indian democracy that political parties that blame the rulers of the day for misusing and abusing constitutional offices such as the judiciary and the Election Commission, the CAG and now the CVC, have done precious little to de-politicise the appointments, elevations and transfers. Individual MPs who take time off to present ‘private member’s bill’ on a host other issues and concerns, knowing full well that they would not pass muster, have never ever attempted one on reforming the EC in particular -- even if it pertained only to future appointments of ECs and the CEC.

N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist and political analyst, is director, Observer Research Foundation, Chennai chapter.