The vituperative campaign against the BJP by the Shiv Sena does not make for an easy post-poll tie-up should either of the two be forced to come together to cobble the numbers. Either must get a clear 145 seats to avoid a forced remarriage to the same political spouse. Any one going with Congress or the NCP only means the platter serves up a goulash, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

The vituperative campaign against the BJP by the Shiv Sena does not make for an easy post-poll tie-up should either of the two be forced to come together to cobble the numbers. Either must get a clear 145 seats to avoid a forced remarriage to the same political spouse. Any one going with Congress or the NCP only means the platter serves up a goulash, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

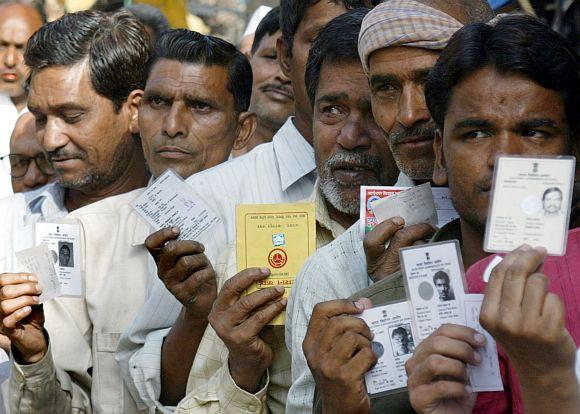

A day after the public campaign for Maharashtra assembly polls ended -- the traditional surreptitious money, liquor, gifts brought into play soon after -- and a day before voting, it can be said the Bharatiya Janata Party is frontrunner, the Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party on the margin vying for the third, fourth and fifth places competing with the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena.

This line up juggled into any order would amount to nothing much unless the voters decide to bring in a single-party rule failing which two distinct possibilities are possible: opportunistic post-poll alliances with old and friends turned bitter foes. The need for a single party rule to regardless of which party heads it would go for a toss.

The state needs single party majority so that the party will not have to make policy compromises to the detriment of the state and explain it away as a coalition dharma. That dharma is actually putting politics ahead of governance, opportunism over principles. But we have stopped expecting principles as part of politics anymore.

The break-ups in the two alliances, the BJP-Sena and Congress-NCP have given the state a chance to break away from the era of coalition politics which has been the mainstay for a quarter century. Compromises have included winking at the other’s corruption, vesting the state’s governance model with a debilitating feature. The state has paid, even as it when the Sena-BJP ruled as partners.

However, the five parties fiercely competing against the others may have only seen the end of electoral coalitions in that former partners did not go together on a joint platform. If the possibility of a single-party majority rule is dumped by the voters, the state enters the phase of post-poll arrangements which can be worse being only tenuous.

The vituperative campaign against the BJP by the Shiv Sena does not make for an easy post-poll tie-up should either of the two be forced to come together to cobble the numbers. Either must get a clear 145 seats to avoid a forced remarriage to the same political spouse. Any one going with Congress or the NCP only means the platter serves up a goulash.

For the first time since the saffron alliance came to be in 1989, the core voters and the floating voters have been asked to opt for either of the two. Hitherto, in alliance, one party was a proxy for the other in the constituencies. To those who batted for a Hindutva thrust in politics, the alliance, not its constituents mattered.

So it was the case between the Congress and the NCP, at times having a myriad set of smaller parties on the bandwagon. The voter’s dilemma of having to reconcile to a substitute from a party not directly favoured by the voter was strong but fated to live with it. But clearer options have also meant witnessing the bitterest campaign.

Civility in the immediate aftermath of political spouses parting is not to be expected. But when these ‘single again’ eye the same fickle suitor -- the voter and power -- it has to be fireworks. Allegations against the partners only a fortnight ago made for a tragicomedy. It was a free-for-all, each marshalling every ounce of effort available, except the Congress.

Bickering emerged as full-fledged war regardless of arsenal, as in the case of Congress and NCP. Their earlier common rivals, BJP and Shiv Sena seemed to take a lower priority. These two also kept going at each other’s throat, except that the former was subdued, leaving room for an opportunistic reconciliation.

In the past, the late Bal Thackeray used to refer to Sharad Pawar as “that bag of potatoes” and in subtle retaliation, be called “Shrimant”, a reference to the Peshwas who ultimately ruined Maratha rule started by Shivaji, given that Sena claimed a legacy of that warrior-emperor. It was clever suggestion that claims of that kind was plain hokum.

Into this quadrangle fight entered the MMS, also retaining its Sena -- or Bal Thackeray pedigree -- as the engaging fifth angle, interestingly postulating an idea. None of the two former alliances, now broken up, either ruled well, or fared as a good opposition, leaving the citizens and the state in a mess of misgovernance.

When the Congress was seen dispirited, with even the national leadership lukewarm to the need to campaign when others were literally on the trot, all anti-BJP parties -- NCP, Sena and the MNS -- took to the idea of Maharashtra versus Delhi. The BJP, as a ruling behemoth in Lok Sabha, epitomised the Big Brother to which status with regional pride shouldn’t bow to.

The communal factor had more or less died down, especially in the elections, with none of the majors inclined to even refer to 2002 in the face of Narendra Modi’s blitzkrieg. But the Majlis Ittehadul Musalmeen fielded 24 candidates to flog the communal angle, its vitriol was worse, or more, than Sena’s and the Sangh Parivar’s had in the past. Its impact would surface sooner or later.

This brought up the Hindu vs the non-Hindus, minorities left out cold by the secular claimants to being their protectors. The Sena and the MNS harped on Maharashtrians vs the non-Maharashtrians, to the extent that Raj Thackeray has to explain to the Election Commission his “no-entry” boards he planned at the state’s borders and turning back outsiders from the railway stations itself.

Sena vented spleen, making Afzal Khan’s army a metaphor for the Delhiwallahs represented by the BJP. MNS wanted autonomy, not having to depend on the Centre to decide how much a traffic violator should be fined. The NCP, apparently on its last legs, wanted an opportunity to rule with at least a simple majority, unhindered by a coalition partner like the Congress.

Having said all this, though the social media, the persistent, high-octane advertising -- TV and print media must be chuckling their way to their banks -- and live telecast of campaign speeches took the element of elections as a tamasha or a festival which is the usual description off the streets, it did render the battlefield fascinating. Fascinating mainly because who the warriors are.