Election manifestos may have lost their earlier importance. But a closer look at them does reveal a lot about a political party’s own assessment of where it went wrong and what its future policy directions will look like, says A K Bhattacharya.

Election manifestos may have lost their earlier importance. But a closer look at them does reveal a lot about a political party’s own assessment of where it went wrong and what its future policy directions will look like, says A K Bhattacharya.

How relevant are election manifestos? Going by the casual manner in which some political parties have been treating their manifestos and the scant attention the media has so far paid to what they promise to the voters, such scepticism is understandable.

The major Left parties have released their manifestos focusing on the need to launch a more effective attack on poverty. Some regional parties too have unveiled their manifestos highlighting the need for decentralised governance. The Congress party has released a detailed manifesto, which is claimed to be the longest ever and produced out of a series of meetings with people at grass-roots level to understand their concerns as well as aspirations.

Significantly, the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, which claims to be the strongest contender to form or lead the next government at the Centre, is yet to bring out its manifesto even though the first phase of the 2014 general elections is less than a week away.

While the BJP’s apathy towards declaring what it stands for and what it wishes to promise to the voters is a disturbing sign for any democracy, the virtual absence of public debate over even the few promises that different political parties have made in their manifestos is a cause for deeper concern.

One reason for the lack of seriousness about election manifestos is the nature of governments that have been formed at the Centre since 1996. Each of them has been a coalition government with support and participation of at least half a dozen political parties.

In a coalition government, the role and importance of individual party manifestos get diluted, if not completely devalued. Indeed, in some coalition governments of the past, the pre-poll manifestos of individual parties gave way to a post-poll common minimum programme.

And in some coalition governments, even a common minimum programme was given a go-by and governance followed neither the manifestos of the coalition partners nor any mutually agreed action plan.

The next government after May 2014 is also likely to be led by a coalition of parties. That perhaps explains why both political parties and even the voters have turned indifferent -- even agnostic -- towards the promises made in manifestos.

The Congress manifesto, however, is a little different and needs to be judged by another yardstick. This is because an election manifesto from a ruling party is not just a statement of intent. More importantly, it becomes an opportunity for the party to make amends where it believes its past policies went wrong and to press ahead with those initiatives that yielded positive results.

Thus, on the question of reviving economic growth, which had decelerated in the last few years of the Congress-led government, the party’s manifesto is categorical about a host of progressive measures such as those on a flexible labour policy (there is even talk of bringing all labour laws under one comprehensive umbrella legislation); expeditious introduction of the goods and services tax and the simplified direct taxes code, both of which should enhance the economy’s efficiency; and giving a push to the manufacturing sector by allowing easier foreign direct investment flows and by committing an investment of over Rs 60 lakh crore in infrastructure in the next decade.

There is also a clear admission of how a few of its taxation laws created problems for industry and the investment climate. While the Congress manifesto has not ruled out retrospective amendment to tax laws, it has advocated caution that risks associated with such laws should be avoided. This is a clear sign that the Congress is trying to learn from its mistakes.

Even on the question of reservation of jobs in the private sector, the Congress manifesto has adopted a tentative approach. It has talked about its commitment to creating national consensus on affirmative action for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in the private sector. The choice of words here is significant. There is no talk of job reservation. Instead, what you get is a promise of creating consensus for affirmative action.

It is true that even the suggestion of such affirmative action has worried industry leaders. But note that the Congress has made a major compromise here. From the earlier stand of reserving jobs in the private sector or asking corporate leaders to put limits on their salaries, all that the party’s manifesto now says is about affirmative action for jobs.

All this is an outcome of the Congress’s recognition of its past mistakes of how its actions and inaction have contributed to an adverse business environment.

In sharp contrast, the Congress manifesto has extended the logic of its policies that seemed to have worked for the party to new areas. The rights-based entitlement programmes -- for food, work and education -- are now proposed to be extended to housing and health care for all. The extension of such entitlement programmes may dent the government’s finances further, but the Congress clearly knows what works for the poor people of this country and what can earn them electoral dividends.

Election manifestos may have lost their earlier importance. But a closer look at them does reveal a lot about a political party’s own assessment of where it went wrong and what its future policy directions will look like.

The Congress manifesto shows that quite explicitly. That is why we should eagerly wait for the BJP’s manifesto.

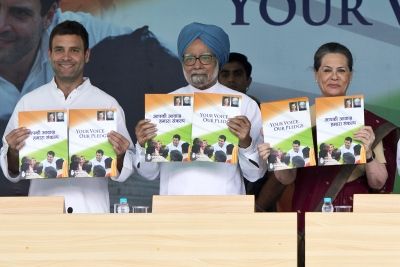

Image: Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, Congress president Sonia Gandhi and vice president Rahul Gandhi present the party's manifesto in New Delhi on March 26, 2014. Photo courtesy: INC website