Why are far right Hindu organisations growing in strength?

Why is there a rising subscription in Neo-Wahabism, the Saudi Arabian version of contemporary Islam?

Mohammad Sajjad takes a closer look at the factors driving communal polarisation in Bihar.

HYV offices have started appearing in some villages of Siwan and Gopalganj districts, north Bihar.

Unemployed youth, with bikes and cellphones, are ready recruits to such organisations.

Photograph: Cathal McNaughton/Reuters

Why are far right Hindu organisations like the Bajrang Dal growing from strength to strength in Bihar?

In the recent incidents of communal violence in Muzaffarpur (January 2015), Vaishali (November 2015), and Saran (August 2016), Bajrang Dal youth were alleged to have indulged in the violence.

The Bajrang Dal -- joined by the community of Mallahs (fishermen) -- is becoming more visible and assertive, specifically in Bihar's Saran, Tirhut and Mithila.

There is a stereotype about the Mallahs. In colonial records, they were identified as 'criminal tribes'. And cutting across religious and caste barriers, the local population have always expressed a certain degree of fear about the community.

In recent times, the Mallahs in Bihar (as well as in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh and other parts) have made efforts towards political organisation and assertion.

The Nishad Samanway Samiti is an umbrella organisation of different sub-castes identifying with the Mallahs, and one of its constituents -- the Ved Vyas Parishad -- was in negotiation with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar in September 2015 before went to the polls.

Their political assertion is aided by the fact that while large swathes of the men of the peasant communities have migrated for their livelihood and children's education, the rate of migration among Mallah males is the lowest.

In migrating, many peasants of the chaurs (low lying waterlogged lands across north and east Bihar) have left their land abandoned.

The soil from these abandoned pieces of land is used by brick makers, and thereby emerge baolis (ponds and pond-lets) within the chaurs.

The Mallahs use these baolis as fisheries without paying anything to the landowners. The chaurs also attract birds. The Mallahs sell their fish and birds, fetching good income.

This economy has its implications.

The preponderant physical presence of the Mallah males in the villages makes them emerge as local toughs.

Their defiance against the absentee landowners (not landlords, as most of them are marginal and middle peasants) by exploiting the chaur lands make them a cohesive group, which has started yielding a political-electoral advantage to them.

Geographically, the commissioner's division of Saran (Bihar) and the Gorakhpur division (Uttar Pradesh) are contiguous, with better road and rail connectivity. The rail contractors and the mafia of Saran-Tirhut and Gorakhpur have been in close contact with each other for decades.

Gorakhpur is also the base of operations of two far right affiliates -- the Hindu Yuva Vahini (HYV, whose chief Yogi Adityanath is now UP chief minister), and the Gita Press.

Now, HYV offices have started appearing in some villages in Siwan and Gopalganj districts, north Bihar, particularly among the Rajputs, as Yogi belongs to the Rajput community.

Unemployed youth, with bikes and cellphones, are ready recruits to such organisations.

Demographically, it appears that a huge proportion of people falling into such groups are from the 18 to 40 age range.

There is a huge mass of youth looking for purpose or fun, and eve-teasers, cow-protectors, and lynch mobs often comprise such age groups.

Communalisation of Muslims

Communal sentiments are also rising among Muslims living in these districts.

The rising subscription to Neo-Wahabism, the Saudi Arabian version of contemporary Islam, poses a problem not only for Hindu-Muslim harmony, but also for intra-Muslim sectarian harmony.

Among Sunni Muslims, the instances of Barelvi-Deobandi/Neo-Wahabi conflicts are becoming more frequent, and quite often these conflicts degenerate into riots.

The age-old practice of marriage ceremonies being attended by members of both communities, Hindus and Muslims, has been undermined.

With rising Neo-Wahabism, a section of pesh imams -- the prayer leaders of village mosques -- have started prohibiting participation of Hindu friends in Muslim marriages.

In some cases, brazenly setting aside courtesy and hospitality (mehmaan-nawazi), Hindu friends of the groom sitting on the stage for the nikaah ceremony have been driven out by maulvis (Muslim clergy) performing the ritual.

In many villages -- under the garb of fighting what they insist on calling shirk and bidat (innovations) of the Barelvi majority -- the Neo-Wahabis are pursuing the politics of one-upmanship and hegemony.

The Barelvis have also come out with a new practice -- processions marking the birth anniversary of Prophet Muhammad. This procession comprising sword-wielding Muslims shouting slogans -- traditionally, such practices were only associated with Muharram -- are led by green flags.

This is often mistaken by Hindus as a Pakistani flag. This is increasingly turning these Muslim villages into a seething cauldron of maslaki (sub-sectarian) conflicts.

In a number of cases, the nexus between the village rangdaars (musclemen extorting money, also called 'frontline functionaries of the state'; in West Bengal, they are called mastans) and the pesh imams is obvious.

Almost invariably, the masjid fund is controlled and regulated by the village hoodlums who also determine the recruitment and dismissal of the pesh imams.

My trips to many villages in north Bihar have revealed that quite a large number of Muslim youth are in a state of denial about the growing influence of Neo-Wahabi radicalism among a section of their co-religionists.

This intolerance, creating obnoxious walls of divide, needs to be fought by those standing for plural values.

The political empowerment of Muslims, and in some cases their affluence, have made it easier for the Sangh Parivar to convince the Dalits and Other Backward Classes, as also the poor among the upper castes, that the 'secular raj' has only benefitted Muslims.

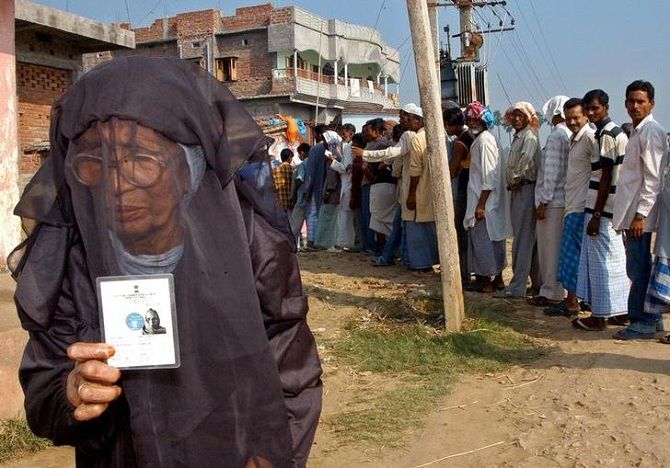

Photograph: Krishna Murari Kishan/Reuters

Widening divide

Meanwhile, the implementation of reservations (soon after Nitish Kumar took over as chief minister in November 2005) in Panchayati Raj institutions for the Ati-Pichhrha -- 28 of the 41 Muslim communities fall in this category; nine in Pichhra and the rest belong to the upper castes -- a number of Muslims find themselves politically empowered.

This too has deepened the conflict between the Hindu and Muslim communities, particularly when it comes to electing the Panchayat Samiti pramukh (chief) and the Zilla Parishad adhyaksh (chairman).

In the elections for these positions, quite often, money and muscle power prevail.

This has resulted in identity-based rivalries as has the display of wealth earned in West Asian countries by neo-rich Muslims.

In Muslim neighbourhoods, each village has some people working in the Gulf countries. With remittances coming in, these neighbourhoods have become more affluent, a fact that has not gone unnoticed.

In recent decades, old mosques have been renovated and expanded, and tall minars (minarets) have been constructed.

The high-rise minars and gumbads (domes) are a conspicuous assertion of Muslim identity, and have become eyesores in Hindu neighbourhoods as Hindu temples are often not built as tall as the minars.

Remittances from the Gulf countries have also been invested in local trading and real estate.

This phenomenon is visible, in varying degrees, in the districts of Gopalganj, Siwan Champaran and Darbhanga.

In these places, some Muslim MLAs and MPs have also been elected in the last two decades.

This conspicuous affluence and political empowerment of Muslims have made it easier for the Sangh Parivar to convince the Dalits and Other Backward Classes, as also the poor among the upper castes, that the 'secular raj' has benefitted only the Muslims.

That such a dispensation needs to be replaced with a party that can protect 'Hindu' interests.

This is a commonly admitted fact among the people of this area -- that the BJP will do dharm-raksha, if not anything else.

Re-assuring steps awaited

Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Lalu Prasad Yadav's elder son Tej Pratap Yadav, who is the MLA from Mahua (Vaishali) and Bihar's health minister, has launched the Dharmnirpeksha Sevak Sangh to fight the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its affiliates.

But he has not articulated the details of the saffronisation of Bihar.

Does he have adequate information about the mushrooming of such organisations across rural Bihar?

Has he diagnosed the socio-economic factors behind such challenges?

Will the DSS be able to take up these challenges?

Does he have the cadre to confront communal forces?

Do he and his cadres have adequate conviction and capabilities?

Many cadres could opportunistically stick to Tej Pratap only so long as he is in power.

Relatively speaking, in the people's estimation, Lalu's younger son, Tejashwi, the deputy chief minister, is supposed to be a more promising leader than Tej Pratap.

But Tejashwi is now under the scanner on corruption charges, which might further weaken the Mahagathbandhan, and brighten the BJP's prospects.

Whether with the RJD or the BJP, Nitish Kumar may continue as Bihar's chief minister, but the real question is how does he wish to go down in history.

As an aide to the far right majoritarian chauvinism, a regime now identified more with lynching? Or as a protector of vulnerable groups at a very frightening moment for them?

It is also possible that given the BJP's fast-expanding social base, both Nitish and Lalu may end up spoiling each other's electoral fate, pushing Bihar into the hellish fire of hate-mongers.

Professor Mohammad Sajjad is with the Centre of Advanced Study in History of Aligarh Muslim University and has published two books -- Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge, 2014), and, Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur since 1857 (Primus, 2014).