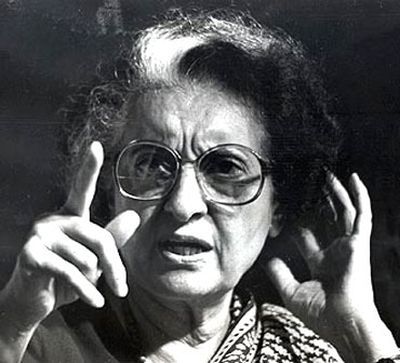

Forty years after the declaration of Emergency by Indira Gandhi, Sunanda K Datta-Ray recalls life when civil rights were suspended and press censorship was in force

Forty years after the declaration of Emergency by Indira Gandhi, Sunanda K Datta-Ray recalls life when civil rights were suspended and press censorship was in force

Silver-haired and baby-faced, Jayantilal Choteylal Shah couldn't contain his laughter. He rolled and giggled in the maroon velvet armchair that had been set for him on a stage in Patiala House. The packed room took its cue from the judge and laughed and clapped uproariously. The cause of merriment was a witness referring to a Delhi municipal official called Tamta as "Tamater sahib".

They were not laughing only at the feeble pun. The real target was Indira Gandhi whose Emergency diktats "Tamatersahib" had slavishly obeyed (like everyone else, one hastens to add). But he hadn't publicly recanted like so many others.

Whether we mourn or celebrate the proclamation of June 25, 1975, it cast aside the alien trappings of law and convention derived from Magna Carta whose 800th anniversary England is now celebrating, and exposed the reality of power in all its desi majesty. Dev Kanta Barooah was right. Indira is India, India is Indira. The India that shaped and sustained Gandhi and nurtured her finest thoughts and actions was also responsible for the vilest, for the victory in Bangladesh as much as Emergency. In turn, she reflected India's vices and virtues.

Not she alone. "The only difference between Indira Gandhi and Charan Singh is that she is a successful dictator and he isn't," a veteran Congressman and barrister Asoke Krishna Dutta murmured in those chaotic post-Emergency months when the Lion and the Unicorn fought for the crown. Senator Adlai Stevenson III wasn't splitting terminological hairs when he pounced on my mention of "representative government" at a Chicago seminar and distinguished it from democracy. Universal adult suffrage had given India representative government, he said. America had democracy. They weren't the same.

The crack that the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and Jaslok Sabha were the country's three power centres reminded everyone that Sanjay Gandhi wasn't the only extra-constitutional authority. The message regarding the fragility of democracy with Indian characteristics was further confirmed as the Shah Commission lumbered ahead like Arthur Miller's savage parody of the McCarthy era in The Crucible.

As I reported in the London Observer at the time, "an ostensibly fact-finding process appears suspiciously like a trial in absentia with a prearranged verdict." Evidence in Gandhi's favour was greeted with cries of "Shame!" Her critics were loudly cheered. The only ban was on smoking. But in mocking her - the ostensible destroyer of "democracy" - the Shah Commission also revealed how thinly the veneers of justice and propriety camouflage the exercise of power. It's a lesson to be remembered in the context of recent happenings involving Lalit Modi, Sushma Swaraj, Vasundhara Raje and other glitterati. Wealth and influence still matter more than institutions and processes.

The Commission's comic entertainment wasn't surprising considering Emergency meant a bonanza for ingenious operators, especially in the media. A newspaper executive frightened minority shareholders into selling their shares for a song to fictitious trusts he controlled. Another media manager became editor through a neat coup. Arguing that Gandhi would find it difficult to grab two publications, he separated the paper's two editions, replaced the one highly respected editor with two dummies and seized editorial control.

The media was up for grabs. A veteran journalist's arrest prompted unkind whispers about pulling strings to realise his ambition to write a book about life behind bars. A young reporter was plucked out and plonked down on the board of directors of a venerable news agency. One of Rajiv Gandhi's school chums was nominated editor-in-chief of a national daily. Lacking that cachet, a lowly assistant editor who merely handled his paper's correspondence columns grovelled before every Congress functionary he set eyes on until he, too, was exalted as editor-in-chief.

Read more stories on the Emergency here

The Patiala House sequel was hilarious. Mouse transformed into lion, he regaled the Commission with bloodcurdling tales of the dragons he had slain in the cause of freedom during those months of the dreaded midnight knock when 110,000 people were jailed. Thus might Captain Jenkins have held forth in Britain's House of Commons when he appeared with a bottle containing what he claimed was his ear that the Spaniards had chopped off. Asked "what his feelings were when he found himself in the hands of such barbarians", Jenkins responded piously, "I commended my soul to God, and my cause to my country!" It's doubtful if Jenkins lost an ear at all. If he did, it was probably in an English pillory for some petty crime. But his speech roused Britain to declare war on Spain in 1793.

My orders were simple. The editor gave each of us a copy of the official guidelines with strict instructions to obey them. He didn't want the censor telephoning at night when he was partying. Press freedom came second to his lively social life. But I did get some fun out of our weekly quotations column. I'd send them to the censor all jumbled up, then, after he had cleared the lot, sort them out in planned sequence. Thus, Gandhi's praise for Sanjay might be followed by a line about some African politician's son being convicted of theft. The censor didn't demand the final layout.

I had to deal with him also on account of my foreign papers. I couldn't telex London but The Observer telephoned regularly and took down my uncensored dictated reports. If anyone asked - no one did - I had a terse letter from Harry D'Penha, the chief censor in Delhi, that everything didn't have to be submitted for clearance. To keep the censor happy, every so often I showed him my weekly column in Australia's Canberra Times. Once it was an interview with a Bihari politician who aspired to oust Jagjivan Ram as a Chamar leader. The censor didn't object to the politicking. His Bengali bhadralok sensibilities quailed only at my mention of the caste. "You're calling an Hon'ble MLA a Chamar!" he exclaimed outraged. "I am not," I explained. "He himself is. And he's stating a fact!" Eventually with many pained cluckings, he agreed unhappily to clear my article.

I was less successful higher up Delhi's official scale. The Germans invited me to visit their country and, as was the rule under Gandhi, sent the letter to South Block to be forwarded to me. The external affairs ministry summoned the embassy's press officer and returned the letter. In the ministry's opinion, I wasn't a fit and proper person to be the German government's guest for ten days.

Sri Lanka followed. When I couldn't oblige one of South Block's Kashmiri pandit mafia who demanded that The Observer should publish a long, convoluted and accusatory speech by Gandhi, he vetoed my covering the 1976 Non-aligned summit in Colombo. The editor buckled in. But to everyone's chagrin, I went all the same despite a forest of hurdles. My passport wasn't valid for Sri Lanka. I didn't have a Sri Lanka visa. I would not be included in the Indian press corps. David Astor, The Observer editor, took care of everything. His secretary telephoned from London to say if I applied the next afternoon my passport would be endorsed for Sri Lanka. She telephoned again to say I would get a visa on arrival. As for exclusion from the Indian press corps, the identity card they gave me in Colombo read embarrassingly "Country: United Kingdom."

Priya Ranjan Dasmunsi, who was in the political wilderness then, described the three faces of Gandhi. "The masses see her as a goddess," he said. "Intellectuals find her an enigma. But those of us who have worked with her know she is stark terror!" The British Labour politician, Michael Foot, praised her Emergency as "a smack of firm government" but chatting at his house in Hampstead 28 years later, he exploded, "Where you got that from I don't know. I said no such thing!" A fallen idol is an object of contempt. Even the taxi driver taking me to 12 Willingdon Crescent (where Gandhi gloated that Europeans visited India to see the Taj Mahal, Qutb Minar and her) thought I was wasting my time.

Emergency was especially degrading because it encouraged posturing at every stage. Gandhi never stopped playing Joan of Arc. "I was perpetually being burned at the stake" she said of her childhood fantasies. The death in 1973 of Chile's Salvador Allende was ominous proof of "the foreign hand." There were wicked rumours when Lalit Narayan Mishra was murdered in 1975 that the "hand" was far from foreign. So persistent were they that Gandhi told a condolence meeting for the dead railway minister, "Even if I were to be killed they would say I myself had got it done." Seven months later she claimed the fate planned for her had befallen Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

She wouldn't have been surprised at a hirsute Ramdev discarding the scarlet robes of godliness and trying frantically to hide the bushy jungle of his beard in a dupatta as he fled the Ramlila Maidan. Caught despite the disguise, the yoga performer delivered a surprising piece of bombast. "It was not a sign of weakness to be in a woman's dress," he declared. "A mother gives birth to a man!" Narendra Modi and Subramanian Swamy must proudly have flexed their Khalsa warrior muscles when they disguised themselves as Sikhs during Emergency.

Of course, Rahul Gandhi's charge that Modi is desperate to stamp out any "institution that is constitutional, that people have faith in" and replace it with personalised power is partisan hyperbole. But revelations about the other Modi confirm that the underlying rationale of Emergency - that laws protect the lawless - has not changed much in these 40 years. Adlai Stevenson might have added that the mechanism of democracy foisted on an impressionable electorate steeped in traditional values creates an elective monarchy. Narendra Modi, also in effect a directly elected prime minister, also demonstrates that such a monarchy need not enjoy an absolute mandate to exercise absolute power. Less than 44 per cent of voters supported Congress at the peak of Mrs Gandhi's triumph; Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party claims only 31 per cent.

Before me as I write is a yellowing single-page special edition of a newspaper published on June 26, 1975. "Internal Security in Danger" it says above the bold headline "PRESIDENT PROCLAIMS EMERGENCY". It's my souvenir of the apogee of absolutism whose spectre will continue to haunt India until India's representative government matures into the kind of democracy Americans enjoy.