'Does the country risk being enclosed in a geographical cocoon if it spurns a multi-continent project for which everyone else has signed up,' asks T N Ninan.

China has started trains all the way to Duisburg on the Rhine, Tehran, and London where there was much excitement. These are the early evidence of what Beijing's One Belt One Road, OBOR, mega-plan is supposed to achieve in terms of transport networks and economic integration.

The Tehran service is reported to have reached eastern China in 14 days through some difficult terrain. But an average container ship could get from Bandar Abbas in the Persian Gulf to Shanghai in about the same time, and should cost less because sea travel is cheap.

The train from Duisburg in Germany will reach China faster than a ship, but here's the thing: These freight trains carry fewer than 50 containers each, whereas a container ship would carry 12,000.

Last year, China sent 1,700 trains to Europe. Equivalent freight would have fitted onto seven or eight container ships.

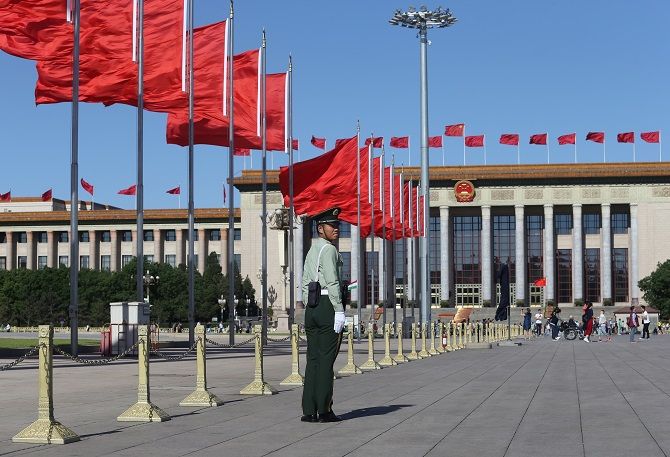

Still, the world is amazed by (while also wary of) the size, strategic ambition and speed of the OBOR project, with some 60 countries said to be taking part in creating six massive economic corridors radiating in all directions from China, and with maritime pivot points all the way to Europe, where it has bought Greece's second-largest port.

The logic offered is that China will relocate some of its low-value manufacturing to low-cost countries along the corridors, that it will use its spare production capacity of things such as steel, and that it will integrate much of the world with China so as to establish Chinese technical and engineering standards in the region, promote the use of the renminbi, set up showpiece bullet trains in half a dozen countries, and such.

That is all good for China, but what about the 60 countries?

Thailand has already said no to a high-speed train from China that was to reach all the way south to Singapore.

Sri Lanka felt it had taken on too much debt because of Chinese port and related projects, but China is back in the game there.

Many African and South American countries have come to regret past Chinese investments in extraction industries.

Even in a client State such as Pakistan, questions are being asked about the viability of some of the projects that are part of the $46 billion investment proposed for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Certainly, the proposed railway and pipeline from Gwadar up the spine of Pakistan and across the Karakoram to Sinkiang makes little sense, given the likely volume of traffic and cost.

Regardless, OBOR rolls on.

India is the last man standing when it comes to OBOR.

Russia is less than enthusiastic about Beijing's outreach, but needs Chinese investment and has signed on for a high-speed train link.

India alone is manifestly hostile to the whole project, partly, but not only, because of the sovereignty issue over Pakistan occupied Kashmir, through which the China-Pakistan corridor will run.

India is also noticeably unenthusiastic about a transport link from Kunming in south-west China through Myanmar and via India to Bangladesh where China would like to set up a deep-sea port, to complete India's maritime encirclement.

It is fine to watch out for one's interests, but the question is increasingly asked: Does the country risk being enclosed in a geographical cocoon if it spurns a multi-continent project for which everyone else has signed up?

It would help if India could get its own regional connectivity projects off the ground, but such diplomatic ambition is punctured by incompetence.

The Chabahar port in Iran that was to provide a route into Afghanistan and into Central Asia has made little headway.

Providing connectivity to the north-east through an Indian-built port at Sittwe in Myanmar and then up by river is half done but useless because the final road link into Mizoram is still awaited.

The long-talked-about road and rail lines through Myanmar to Thailand and deeper into south-east Asia are nowhere near reality.

If we don't want to be a splendidly isolated country that is at a disadvantage in key markets, perhaps we should ask the Chinese to build our connectivity projects for us.

DON'T MISS features in the RELATED LINKS BELOW...