While the state’s decision to take the road to Prohibition has been given a communal twist, there are several political imperatives of the move

If Biju Ramesh is worried, he does not show it. Seated behind a large desk in his spacious office in Thiruvananthapuram filled with pictures and statues of various Hindu deities, the president of the Kerala Bar Hotels Association sees a communal conspiracy behind the Kerala government’s move to close all bars in the state save those in five-star hotels in less than 15 days. The policy, ratified by the Kerala cabinet on Wednesday, also says 10 per cent of the retail liquor stores in the state would be closed every year till there is none left by 2023. It comes four months after the state government refused to renew 418 bar licences after the comptroller and auditor general found them substandard. “Of the bars which were denied renewal, at least 70 per cent belonged to Hindus. It was at the insistence of the Church that (Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee president V M) Sudheeran said those licences should not be renewed,” says Ramesh, a portly figure in a white striped shirt and a dab of sandalwood paste on his forehead.

If this sounds far-fetched and unsettling, that is the direction in which the discussion over the Oommen Chandy-led United Democratic Front government’s steps to introduce Prohibition is being steered by certain sections. The master of this spin is Vellappally Nateshan, the powerful general secretary of the Sri Narayana Dharma Paripalana Trust which has a significant following in the Ezhava community: he came on air soon after Chandy announced the new liquor policy to suggest if bars could not serve liquor, the Church should not be allowed to serve wine for the Holy Communion ritual.

Each of the two says he is speaking as a representative of his community or association. But they have personal stakes in it as well. Ramesh runs nine hotels in Thiruvananthapuram, which lost their bar licences in April. The new policy has dashed any hope Ramesh may have harboured of reopening the bars. He claims he has already lost Rs 40 lakh. Nateshan owns four bars. Many others had started building hotels without any inkling of this bolt from the blue, taking loans for their projects. Even the banks won’t be spared the blow.

Thus, while one can dismiss the conspiracy theories behind the decision, the proposed closure of the remaining 312 bars in the state and 10 per cent of the 384 retail liquor stores will have very real, far-reaching implications for a state which earns around 16.4 per cent of its revenue (2012-13) through the sale of alcohol. Alcohol retail stores in Kerala are run exclusively by state-owned Beverages Corporation and Consumerfed. In 2012-13, the two reported a turnover of Rs 8,818 crore, of which Rs 7,240 crore went to the exchequer. Apart from loss of revenue to the state and the jobs of those directly employed in the sector, the other big casualty could be the tourism sector, which generates an income of over Rs 20,000 crore and provides employment to a million people. Kerala has few other industries, apart from the services sector, and the state attracted over 15 million tourists last year and revenue of over Rs 20,000 crore in 2012-13. What, then, pushed Chandy to announce a slew of measures that would make the state liquor-free by 2023 and possibly turn away many tourists?

“Political drama” is what anybody will tell you, from the man on the street to even the hardened proponent of Prohibition. “There cannot be an argument that this decision is politically motivated,” says former chief secretary Babu Paul. The dramatic announcement was the climax of a feud in the faction-rid Congress in Kerala. On one side was Sudheeran, a well-known advocate of Prohibition, who took charge of the party unit in February.

He would like to be the undisputed leader of the state, perhaps through an interim election if it comes to that. Ranged against him was Chandy, the chief minister, who has been surviving on a wafer-thin margin and depends on the Indian Union Muslim League and Kerala Congress (Mani) for survival; so an early election is not too improbable a scenario.

Sudheeran reportedly insisted that the licences of the 418 bars found substandard by the CAG shouldn’t be renewed this year (renewal used to be a more or less automatic process for an annual payment of Rs 23 lakh). While the bar owners went to court, Sudheeran dug in his heels and found support from the Catholic Church and the Muslim League. Cornered, Chandy did one better: he put Kerala on the road to Prohibition by 2023. The first lot of retail stores will shut on October 2.

While the decision caused outrage in most quarters (and spawned a host of jokes and memes) and raised questions about the efficacy of Prohibition, there are many who welcome the decision. Various flex boards have popped up by the roads hailing Chandy, Sudheeran or both for their “boldness” and photographs of Chandy being feted by schoolchildren have appeared all over. Some of it could be plain propaganda, but there’s no denying that alcoholism has been on the rise in Kerala and has brought along issues such as increased domestic violence and road accidents.

“Where will he go now?” says Usha Devi (name changed on request), a giggle inadvertently escaping while wondering how her estranged husband will manage to get his mandatory “fix” of alcohol if the government does indeed implement Prohibition. It has taken a while for the slim, middle-aged postgraduate to get to this stage when she can laugh about this, having suffered abuse at the hands of her alcoholic husband for 15 years, till their two sons told her to escape from home. She finally sought refuge in Abhaya, a shelter for women in Thiruvananthapuram started by social activist and poet Sugatha Kumari, a renowned literary figure in the state and vocal campaigner against alcoholism. Women like Usha Devi and Kumari are among those who hail the government’s moves. “We have been asking the state government to control the consumption of alcohol for the past 40 years,” says Kumari.

The Church, too, has been active in condemning alcoholism and has leaned heavily on the government to be more active in taking steps to curtail supply, with some Catholic bishops even going so far as to say the government would fall if Prohibition was not introduced. “Families are disintegrating, atrocities against women and abuse of children are rising and the root cause of all this was found to be alcohol. We could not close our eyes to what was happening around us,” explains Father Varghese Vallikkatt, deputy secretary general of the powerful Kerala Catholic Bishops’ Council.

At 8.3 litres, the state has the highest per capita consumption of alcohol in the country. And even this figure, say activists, is outdated. More than that, there is growing evidence of alcoholism amongst school-going children. “Thirteen-year-olds have started walking into bars, stuffing their uniform in their school bag and downing pegs of hard liquor,” says Kumari. “The first use of alcohol has shifted to early adolescence and its use while in school has been increasing over the last five years. Many students go out during their break in groups to get a drink,” adds Nazeer E, social scientist at the department of psychology in Thiruvananthapuram Medical College. The hospital’s de-addiction and counselling centre where Nazeer works has conducted interventions at school level to spread awareness about the detrimental effects of alcoholism. The social acceptance that drinking has received is a key factor for this, he says, as is the easy availability of alcohol.

Johnson Edayaranmula, director of the Alcohol and Drug Information Centre and a member of the advisory group on non-communicable diseases, set up by the Indian government and the World Health Organisation, says the organisation’s research, too, has shown that the age of initiation has crashed to 13 and drinking among youth has jumped from 2 per cent in 1990 to 18 per cent now. Edayaranmula has been campaigning against alcoholism for some 40 years, from his days in college when he used to traverse the state giving speeches against alcoholism and spreading awareness among the youth. “One in four hospitalisations is now alcohol- or drug-related, as are 40 per cent of road accidents and 80 per cent of divorce cases,” says the bespectacled activist at his residence-cum-office in the state capital.

It is precisely because of all these factors and the widespread notion that alcoholism in Kerala is rising and needs to be tackled immediately that no political leader could speak out strongly against Chandy’s trump card. The Opposition Left Democratic Front had practically no choice but to welcome the move, whatever reservations it might have about the efficacy, feasibility and practicality of Prohibition. Chandy himself risked being perceived as being hand-in-glove with the “liquor lobby” if he did not come out with a strategy to counter Sudheeran’s hectoring against alcohol. This could also be why those with direct stakes in the game and crores to lose have to resort to stoking communalism in their attempt to persuade the government to roll back the decision.

Yet, Edayaranmula, like many others, expresses scepticism about the government’s announcement. “It is merely the culmination of a political melodrama. There has been no groundwork done to assess the extent of the problem, and there isn’t enough enforcement muscle to implement the decision,” he says. There are reasons for scepticism about the government’s sincerity, as Edayaranmula and many others point out, and as was underlined in announcements after the state Cabinet meeting on Wednesday. For one, while notices have been served to shut bars, there has been no word from the government about wine and beer licences. The consumption of beer has been steadily increasing in the state, from 7 million cases in 2008-09 to 10 million cases in 2012-13 (IMFL sold 24 million cases in 2012-13). Latest reports suggest some 400 hotels in the state are eligible for a beer licence, the fees of which was raised from Rs 4 lakh to Rs 5 lakh, and many hotel owners would be opting for it. The Cabinet is also yet to decide on the sale of alcohol in “elite clubs” and in the armed forces canteens (much of the alcohol sold here ends up in civilian bellies). The sale of toddy will also not be impacted.

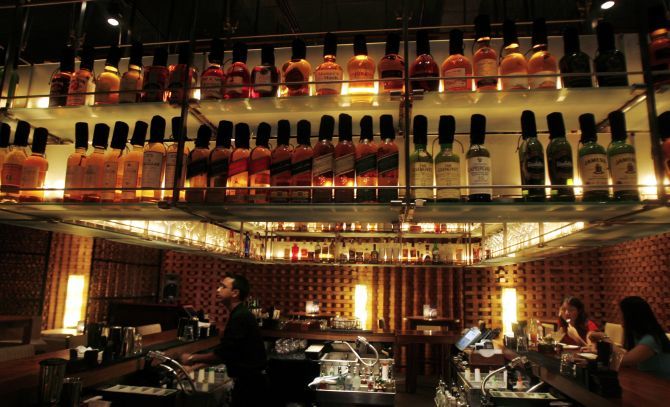

Most important, the shutting of the retail liquor outlets run by the state will be spread over a decade — not only would the current government have to stick to the policy, so will the next two governments voted to power. The same Chandy government which has now declared its intent to introduce Prohibition also initiated the opening of a swanky 4,000-square-foot retail liquor outlet in Ernakulam in June. It is well-lit and air-conditioned, with the alcohol (mostly premium brands) neatly arranged in shelves, as in a supermarket. The shop is worlds away from the average dingy Beverages Corporation outlet where one has to queue up for one’s poison of choice, but it also raises questions about the government’s commitment to the cause.

Images: Reuters