His other big achievement -- of avoiding a partition of South Africa against a determined bid by Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi has not received much attention. He was thus a Mahatma Gandhi and Abraham Lincoln rolled into one. Preserving a united South Africa against western intrigues was indeed a signal achievement, says Colonel (retd) Anil Athale.

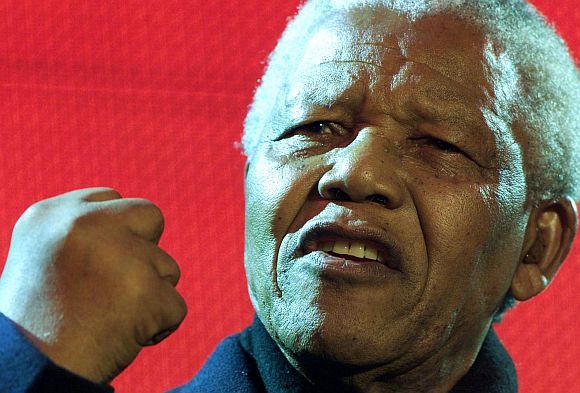

Historians will record Nelson Mandela, who passed away on Friday at the age of 95, as the greatest political leader of the 20th century. Much has been written about and will be written about his extraordinary feat in healing the racial breach in South Africa. It was indeed a historical achievement by any standard.

But in the view of this author his other big achievement, of avoiding a partition of South Africa against a determined bid by Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi has not received much attention. He was thus a Mahatma Gandhi and Abraham Lincoln rolled into one. Preserving a united South Africa against western intrigues was indeed a signal achievement.

He can also be called the father of South African democracy. He established the true democratic traditions by walking away from power in 1999 after just one term as President. These achievements make him undoubtedly the tallest leader of the last century.

It was in 1993 that this author met a distinguished South African professor of political science who was also an African National Congress’s rare white activist. In discussions we found tremendous parallels between partition of India in 1947 and situation in South Africa in 1990s. South Africa was at that time going through a very turbulent period. Mandela was released in February 1990 but instead of the promised peace, the nation was rocked with greater violence.

In the four years between 1990 and 1994 over 20,000 people died in violence between the IFP (Inkatha Freedom Party of the Zulus) and the largely Xhosa-dominated ANC. There was an uncanny resemblance between what was happening in South Africa in the 1990s and the happenings in India between 1945 and 1947. Chief Buthelezi was playing the role performed by Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Buthelezi launched the equivalent of Jinnah’s ‘direct action’ (mass killings/riots). Zulus, like Muslims in India, had memories of having ruled over the entire country, were more warlike than the majority Xhosas, were in greater number in the armed forces and formed a majority in the Natal province. Like Jinnah earlier, Buthelezi was also associated with ANC and the anti-apartheid struggle but later broke away and pursued a ‘separatist’ agenda.

The white regime and western powers clandestinely supported Zulu separatism as they did Jinnah’s Muslim League. Of course there were major differences in the two situations. The ANC unlike the Indian National Congress had an armed wing Umkhonto (MK) or the ‘Spear of the nation’ and gave it back as it got. The South African professor and this author came to the conclusion that there was a real possibility of South Africa following the Indian subcontinent and being partitioned with a separate Zulu land. An article written jointly by the two of us was published in leading South African newspaper at that time.

But then none had reckoned with the genius of Mandela.

One of the major demands of the Zulus was for regional autonomy and special status. By accepting the position of the Zulu Monarch, Mandela neutralised a large measure of support for Buthelezi. Forced by the public opinion as well as fear of violence from MK, Buthelezi’s IFP participated in the 1994 elections and won 10 percent of national vote and 51percent vote in the Zulu-majority Natal province.

On May 10, 1994 as Nelson Mandela was sworn in as the first black President in the history of South Africa, he made Buthelezi the country’s home minister, a post he continued in for the next 10 years. Mandela successfully tackled the real challenge of Zulu separatism unlike Jawaharlal Nehru and Gandhi in 1947.

Many African nations have faced constant violence due to strong tribal ties and a culture of inter-tribe wars. When he completed his term as President in 1999, Mandela walked away from power, showing great humility and also showing that he was not indispensible. This was also a very shrewd move as he guided the ANC government from outside with a carefully crafted succession policy of giving power to representatives of all the three major tribes in turn. The current President of South Africa is a Zulu. Inkatha and its separatist movement are a distant memory.

Many commentators in India have been calling Mandela South Africa’s Gandhi. This is unfair to both these great men. Mandela was not as rigid a follower of non-violence as Gandhi was. His use of MK in ending the separatist struggle of Zulus is well documented. Unlike Gandhi’s denunciation of revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh, Mandela never under estimated or belittled the value of violent struggle.

The famous ‘Rivonia Trials’ in 1963-64 were a watershed in the life of Mandela and South Africa. These trials were the outcome of a raid by the South African police on the farm, Lilliesleaf at Rivonia near Johannesburg, on July 11, 1963. The trial was the most famous in the history of South African political resistance. Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and others were sentenced to life imprisonment on June 12, 1964.

This marked the virtual end of the peaceful struggle waged by the majority black Africans and can be said to be the beginning of the armed struggle, not out of choice but out of compulsion. Much before the arrest in 1963, the ANC in its annual conference chalked out a plan to carryout underground violent struggle in case it was banned. Known as the M-Plan (Mandela Plan), ground work was laid to carry out underground struggle on the lines of Communist revolts in other parts of the world.

The formation of volunteer corps wearing uniforms and swearing an oath during the defiance campaign of the 1960s, were the first tentative steps towards formation of the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK for short) that meant ‘the spear of the nation’.

The MK was a hierarchical organisation with a clear ‘top-down’ character. In Mandela’s words, ‘The idea was to set up an organisational machinery that would allow the ANC to take decisions at the highest level which could then be swiftly transmitted to the organisation as a whole without calling a meeting.’

At the same time the plan had important features promoting local initiative and participation. The smallest unit was a cell, which in urban townships consisted of ten houses on a street. A steward was in charge of the cell. If the street had more than ten houses then there would be a cell steward and street steward. A group of streets formed a zone directed by a chief steward who was in turn responsible to the local branch of the ANC secretariat. Thus an elaborate and structured organisation came into being much before the ban on the ANC or the eventual armed struggle of 1976. One of the ironies of the M-Plan was that it was actually the racist regime and its plans for segregated townships that helped it form secure bases for the underground work.

There was very little underground or armed activity following the formation of MK as the local conditions meant that the force had to be trained outside the country. But what M-Plan did was to create the ‘sea’ in which the guerrillas could operate once they managed to enter.

Mandela is often compared with Nehru as nation builder and with Bishop Desmond Tutu as his Gandhi providing ideological support. But in two respects Mandela proved himself to be a cut above Nehru. He showed his total faith in democracy by quitting after just one term and despite having many progeny, never tried to create a Mandela dynasty.

On a research visit to South Africa in 2008, this author met many of his close associates but was unable to meet the great man himself -- his health was on a decline and getting to meet him was to punch well above my weight. However history will regard him as the greatest leader of the 20th century.

Colonel (retd) Anil Athale had visited South Africa in August 2008 as USI’s Shivaji Fellow to study the anti-Apartheid struggle.