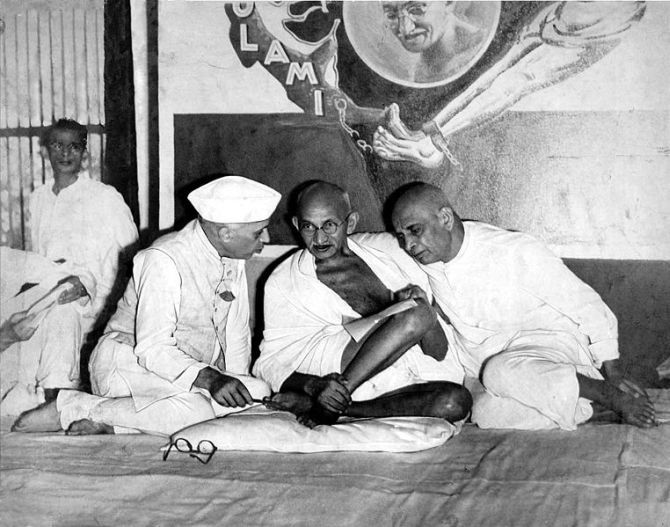

When Nehru came in active contact with Gandhi 100 years ago, he was a Westernised rationalist while Gandhi was deeply soaked in the Indian ethos and spirituality, notes Rasheed Kidwai.

Temperamentally and culturally, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru had little in common, but the Father of the Nation had 'spiritualised' the country's first prime minister.

When Nehru came in active contact with Gandhi 100 years ago at the time of the anti-Rowlett Act agitation followed by the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre in 1919, he was a Westernised rationalist while Gandhi was deeply soaked in the Indian ethos and spirituality.

Throughout most part of the freedom struggle, Gandhi differed with Nehru on the village economy, non-violence, religion and economic thinking.

D G Tendulkar in Mahatma (Volume VI, page 43, Times of India Press, Bombay) has quoted Gandhi as saying, 'Somebody suggested that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and I were estranged. It will require much more than differences of opinion to estrange us. We had differences the moment we became co-workers, and I have said for some years and say now that not Rajaji but Jawaharlal will be my successor.'

This was in 1942 and Gandhi again spoke in Nehru's favour before the installation of an interim government in September that year.

It was clear to all that the designated vice president of the interim government would be the prime minister once the country attained Independence.

Nehru spoke about Gandhi to visiting French journalist Tibor Mende almost a decade after Gandhi's assassination, admiring his mentor, 'He (Gandhi) always referred to Ram Rajya. To a person like me this sounded like going back to some primitive state, but that was a phrase which was understood by every villager... The point is that Gandhi was always thinking of the masses and the mind of India and he was trying to lift in the right direction' (page 36, Conversations with Mr Nehru, Secker and Warburg 1956).

Elaborating further, Nehru told Mende, '...In spite of my differences with Gandhi; more and more I come to believe in him as a tremendous revolutionary force in the right direction.'

Nehru also admitted candidly that Gandhi spiritualised him, 'This (spirituality) is the kind of influence Gandhi had on a vast number of people. It changed the whole manner of living.'

In his autobiography too, Nehru had paid handsome tribute to Gandhi, 'Always we had a feeling that while we might have been more logical, Gandhiji knew India far better than we did, and a man who could command such tremendous devotion and loyalty must have something in him that corresponded to the needs and aspirations of the masses.'

Gandhi paid Nehru a huge compliment on October 3, 1929, when he spoke about the young Congress president, 'In bravery, he is not to be surpassed. Who can excel him in the love of country? He is rash and impetuous, say some -- and if he has the dash and rashness of a warrior, he also has the prudence of a statesman -- he is pure as a crystal, he is truthful beyond suspicion. He is a knight sans peur, sans reproche -- the nation is safe in his hands' (page 185, The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi: 1 September, 1929 - 20 November, 1929, Volume 47 Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1994).

Gandhi also admitted his differences with Nehru. Tendulkar has quoted him as saying, 'He says he does not understand my language, that he speaks a language foreign to me. This may or may not be true. But language is no bar to union of hearts. And I know this -- that when I am gone he will speak my language' (page 43; Tendulkar D G's Mahatma, Volume VI, Times of India Press, Bombay).

Nehru was 20 years younger and a self-confessed disciple of Gandhi. But on some issues, their disagreement continued offering two shades of opinion for the Congress party which claims to follow their footsteps.

Gandhi was a traditionalist whose political perspective had a strong dose of faith, more precisely the Hindu religion.

Nehru, on the other hand, was a rationalist, a product of the Western liberal tradition. For him, reason was key to understanding and action and he was opposed to the idea of mixing religion with politics.

Gandhi, throughout his political life, relied on instinct, intuition and mystical insight to reach his conclusions.

Gandhi did not approve of the Nehruvian thrust on socialism or planning for the growth of a backward economy. Barely hiding his disapproval, he wrote to Agatha Harrison on April 30, 1936 stating, 'But Jawaharlal's way is not my way. I accept his ideas about land etc. But I do not accept practically any of his methods' (cited in Jawaharlal Nehru's A Bunch of Old Letters, Asia Publication House) and added, 'In my opinion, his planning is a waste of effort. But he cannot be satisfied with anything that is not big.'

For Gandhi, non-violence was a weapon of the strong and a non-negotiable political expression that had to be practised under all circumstances. 'Liberty and democracy become unholy when their hands are dyed red with innocent blood' (page 70, New Directions Publishing).

But his political heir had a different take. Nehru wrote, 'Violence is the very lifeblood of the modern State and social system. Without the coercive apparatus of the State, taxes would not be realised, landlords would not get their rents and property would disappear' (page 540, An Autobiography by Jawaharlal Nehru, Oxford University Press).

Nehru also had no qualms in telling Gandhi how 'Democracy indeed means the coercion of the minority by the majority' (the expression majority and minority was in the context of numerical strength rather than religious identity of communities).

In the Gandhian scheme of things, no man could live without religion. Gandhi wrote in his An Autobiography -- The Story of My Experiments With Truth (page 69), 'There are some who in the egotism of their reason declare that they have nothing to do with religion... My devotion to truth has drawn me into the field of politics... those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.'

Nehru did not relent and went on to argue, 'Often in history we see that religion, which was meant to raise us and make us better and nobler, has made people heave likes beasts. Instead of bringing enlightenment to them, it has often tried to keep them in the dark; instead of broadening their minds, it has frequently made them narrow-minded and intolerant to others' (Page 37, Selected Writings of Jawaharlal Nehru, 1916-1950, Edited by J S Bright, Indian Printing Works, New Delhi).

Rasheed Kidwai, author and journalist, is a visiting fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.