'Vijay Gokhale's appointment as foreign secretary can be regarded as a certain 'adjustment' that could make a difference to the poor climate of India-China relations,' says Ambassdor M K Bhadrakumar.

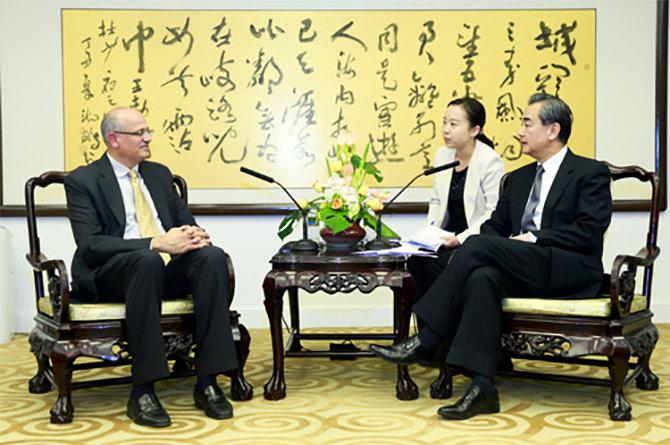

IMAGE: Vijay Gokhale, the outgoing Indian ambassador to China, pays a farewell call on Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, October 21, 2017. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China

The Indian media failed to take note that the Chinese foreign ministry Web site featured a rare account of the meeting between Foreign Minister Wang Yi and an 'outgoing' foreign envoy in Beijing last October.

The envoy happened to be the then Indian ambassador Vijay Gokhale who was being reassigned, and leaving China.

It is customary for departing envoys to pay farewell calls on the foreign minister of the host country before taking the voyage home. But it is unusual that Beijing selectively highlighted the meeting.

This was more so, since the meeting between Wang and Gokhale took place barely weeks after the denouement to the Doklam faceoff that had apparently brought the two countries to the brink of war.

The Chinese foreign ministry account flagged Beijing's high appreciation of Gokhale's assignment in China. Both Wang and Gokhale were 'forward-looking' in their remarks, stressing in particular the 'consensus reached by the leaders of two countries as guidance.'

Wang once again stressed the importance of strengthening 'mutual strategic trust'.

In sum, the exchange between China's top diplomat and the departing Indian envoy was anything but routine.

IMAGE: Vijay Gokhale presents a copy of his credentials as India's ambassador to China to China's director general of protocol. Photograph: Kind courtesy: MEA

Two months later, when the announcement came in the first week of January that Gokhale would be India's next foreign secretary, the Global Times newspaper devoted a full commentary to analyse the importance of the news.

The commentary was authored by a noted Chinese strategic analyst of Indian foreign policies and economy, Liu Zongyi.

Liu cast Gokhale as a 'hardliner' on China. Actually, no surprises here, because foreign service officers do fight like lions to defend India's national interests even if the style may vary from person to person.

However, what gave food for thought was the assessment by Liu that Gokhale's appointment 'demonstrates that his diplomatic skills appeal to Modi.'

'It also indicates that India will continue its hardline stance toward China, except slight adjustments in keeping with the international situation.'

That was a startling assessment, because it was predicated entirely on the notion that India's prime minister is the 'final arbiter of diplomatic policy' on Raisina Hill while three agencies cook up the policy options for him -- the prime minister's office, the national security advisor and the ministry of external affairs.

Of course, that is a simplistic notion of a complex situation that often borders on the absurd.

If things were that simple and straightforward, Manmohan Singh would have fulfilled his agenda to find an enduring solution to the Kashmir dispute latest by 2010; the Siachen region in those tangled mountains would have been 'demilitarised' long ago; and Delhi wouldn't have messed up its Nepal policies so badly.

In reality, foreign policymaking has become incredibly complex as India continued to grow and become more demanding. Interest groups have spawned and foreign policy ceased to be a esoteric subject best left to Nehru and Secretary-General N R Pillai ICS.

It is difficult to quarrel with an article in the National Herald newspaper last week that the Washington establishment finds it more convenient and productive to leverage its contacts in the RSS to get their job done in Delhi in recent years rather than waste time negotiating with the mandarins in the foreign policy establishment.

However, there is really no contradiction between Wang's appreciation on the one hand of Gokhale's contribution in promoting India-China relations during a particularly difficult period and Liu's assessment on the other hand that India's hardline China policies will remain on track without any significant shift under the new Indian foreign secretary, apart from some 'slight adjustment in keeping with the international situation'.

IMAGE: Vijay Gokhale with Xia Baolong, then Communist party secretary, Zhejiang. Photograph: Kind courtesy The Indian Consulate, Shanghai

But the point is, even 'slight adjustment' in diplomacy can make a world of difference. For a start, an ambassadorship in Beijing alone doesn't make a diplomat a China expert. A diplomat needs more than a single tenure to begin to understand countries as complex as China (or Russia).

And all accounts uniformly praise Gokhale as an authentic 'China hand'. Hopefully, therefore, there won't be such appalling blunders like the hoisting of the flag of 'independent Tibet' on China's border with India or consorting with the Taiwanese lobby. This is one thing.

Secondly, the only good thing while surveying the wasteland of India-China relations today, it is that the past three years' diplomatic track pursued by the government took India to ground zero.

IMAGE: Vijay Gokhale, then India's ambassador to China, with Han Zheng, then Communist party secretary, Shanghai, now a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, China's highest decision-making body. Photograph: Kind Courtesy: The Indian Consulate, Shanghai

Now that the 'hardline' proved futile (and even counterproductive), a different approach is needed.

In the meanwhile, the international situation has also phenomenally changed, necessitating 'adjustment' in our policies.

Arguably, Gokhale's appointment as foreign secretary itself can be regarded as a certain 'adjustment' that could make a difference to the poor climate of India-China relations.