The solution to the Kashmir problem does not lie in India speaking to Pakistan; it does not lie in the Indian government speaking to the separatists; it lies in the Kashmiris talking to their inner selves. They need to trace their history to include their rich cultural heritage of Hindu Saivism and Sufi mysticism. Only then will Kashmiris be at peace with themselves, says Vivek Gumaste.

The solution to the Kashmir problem does not lie in India speaking to Pakistan; it does not lie in the Indian government speaking to the separatists; it lies in the Kashmiris talking to their inner selves. They need to trace their history to include their rich cultural heritage of Hindu Saivism and Sufi mysticism. Only then will Kashmiris be at peace with themselves, says Vivek Gumaste.

The currents of history do not coalesce together logically or flow smoothly. They pursue an erratic capricious course with an uncanny knack of picking up nondescript incidents or seemingly minor indiscretions that appear paltry and banal at that moment and transforming them into sentinel events of enormous significance whose impact stretches out into posterity for generations.

So in the 1300s, when Devaswami, the head pontiff of Sharada Peeth (the great Kashmiri centre of Vedic learning) in a transient fit of arrogance rebuffed Rinchina’s (a prince of Ladakh and an usurper to the throne of Kashmir) request to be inducted into the Hindu fold, little did he realise the far-reaching consequences that his fateful pronouncement would have for the Hindu community of Kashmir.

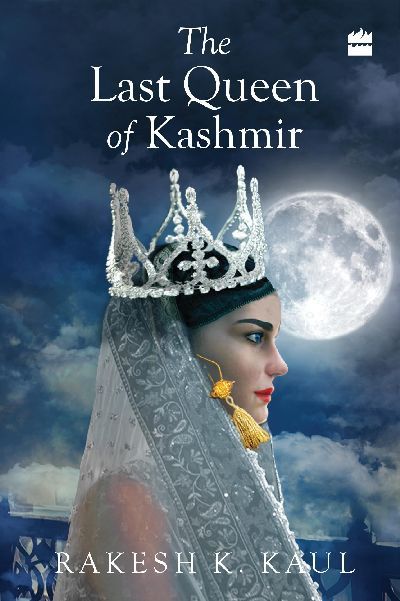

Rakesh Kaul recapitulates the poignant exchange between them in his magnificent historical novel, The Last Queen of Kashmir (2016. Harper Collins, India) which artfully reconstructs early 14th century Kashmir -- a contentious period rife with anarchy and chaos that facilitated the entry of Islam into the cradle of Vedic civilisation.

The book virtually transports one back in time: use of vernacular phrases, flowing references to Vedic shlokas, tongue-twisting Sanskrit terminology, and colourful descriptions of native people and their characteristic clothing infuse the novel with a medieval reality that is impressive and credible.

But more notable than the literary embellishments is the historical fidelity of the narration that is sustained throughout its entirety: the overall plot remains true to historical time lines and rarely deviates from reality.

This saga of 14th century Kashmir courses through a rich and complex plot of personal betrayal, political intrigue and subversive religious proselytisation culminating in a disastrous alteration of ideological demography: the guiding principle of Kashmir -- ‘truth, beauty and bliss through knowledge and consciousness’ -- is thrust aside to make way for a narrow, rigid and alien fanaticism.

Central to the theme is Kotarani, the young beautiful and pragmatic daughter of commander-in-chief turned leader Ramachandra; her life forms the fulcrum around which these events are narrated. When Ramachandra is murdered before her eyes by the turncoat Rinchina, a Tibetan Botha who had been given sanctuary by her father at her behest and with the assurance that ‘from now on you are a part of Kashmir where dharmic justice is the law of the land’, Kotarani lapses into a state of shock.

In pursuit of her vendetta, Kotarani accepts the offer of marriage from a partially repentant Rinchina in order to safeguard the interest of Kashmir. However, Rinchina soon realises that despite his betrothal to the rightful queen of Kashmir, his outsider status persists. He approaches Devaswami for acceptance into Hinduism. When Devaswami demurs, the hurt Rinchina succumbs to the machinations of the wily Shah Mir (another key player in this drama) who manipulates him into embracing Islam -- he thus becomes the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir.

Fortunately for Kashmir, Rinchina’s religious mentor proves to be a benevolent Sufi mystic named Bulbul Qalandar whom the Kashmiri respect and honour: 'The Kashmiris honored Bulbul for his divine insights and in return they were the beneficiaries of his grace. It did not matter what faith you were: Bulbul’s heart was the universal receptor, and the Kashmiris marveled that Islam had produced such a luminous being.'

Nevertheless, this turn of history paves the way for Islam to find a prominent place in the Valley. Shah Mir, an immigrant from Swadgabar who had sought asylum in Kashmir in 1313 with his band of followers and relatives, is a man who harbours mounting political ambitions and is smitten with religious fervour. His religious confidant is a foil to Bulbul Qalandar: an extremist fakir who propounds an aggressive brand of Islam at odds with the pluralistic milieu of Kashmir.

Together, the fakir and Shah Mir plan on a strategy.

Coincidentally, fear of invasion by barbaric and fanatic religious raiders like Dulucha and his Ghazi warriors who demand zan, zamin and zenana (gold, land and women) along with religious submission hangs heavy over the kingdom of Kashmir.

Thus, internal and external forces collude to undermine the native philosophy of Kashmir.

Meanwhile, Shah Mir with fake humility and cunning ingratiates himself to the system rising to be the commander in chief of the kingdom, all along coveting the throne of Kashmir. Once firmly ensconced in a position of authority he resorts to outright political murders, stages dissent and corners Kotarani into submission.

In response to his precondition for marriage Kotarani kills herself on July 17, 1339, and Shah Mir establishes the first Muslim dynasty of Kashmir, a dynasty that would ring the death knell of Hinduism in Kashmir through its descendants like the notorious Sikander Butshikan (1389-1413), the iconoclast during whose reign forced proselytisation reached a peak.

In barely 100 years, by the end of Sikandar’s regime, the demography had been irreversibly altered to leave a lasting impact on Kashmir.

The striking parallels between those times and modern-day happenings in Kashmir is hard to ignore: history does not go away, it repeats itself.

On January 19, 1990 (known as the Kristallnacht of Kashmiri Pandits), the ghosts of Dulucha and Sikandar once again returned to Kashmir. On that cold wintery night as the frightened Pandit community cowered behind closed doors, mosques in Kashmir blared out a warning as all law and order collapsed: “Kashmir mei agar rehna hai, Allah-O-Akbar kehna hai” (“If you want to stay in Kashmir, you have to say Allah-O-Akbar”); “Yahan kya chalega, Nizam-e-Mustafa” (“What do we want here? Rule of Shariat”); “Asi gachchi Pakistan, Batao roas te Batanev san” (“We want Pakistan along with Hindu women but without their men”).

ALSO READ: 19/01/90: When Kashmiri Pandits fled Islamic terror.

The spirit of Sharadapeeth and Baba Qalandar still lingers on in the Valley albeit in a muted form but so do the likes of Shah Mir and the fanatic fakir.

The solution to the Kashmir problem does not lie in India speaking to Pakistan; it does not lie in the Indian government speaking to the separatists; it lies in the Kashmiris talking to their inner selves and coming to terms with their whole identity -- their past and their present.

They need to trace their history from the beginning of time to include their rich cultural heritage of Hindu Saivism and Sufi mysticism. Nobody is asking them to negate their Muslim persona but to be true to themselves and their ancestors they must accept their Hindu past that stretches back 5,000 years. Only then will Kashmiris be at peace with themselves.

The Last Queen of Kashmir is a tour de force that is informative, entertaining as well as edifying.