Most of the punditry is wrong. There is no one lesson from the Delhi election, only what the three parties choose to believe -- but what will they choose, asks Mihir Sharma.

Most of the punditry is wrong. There is no one lesson from the Delhi election, only what the three parties choose to believe -- but what will they choose, asks Mihir Sharma.

Vast amounts of nonsense is already being written and said about the Aam Aadmi Party's epic come-from-behind sweep of Delhi's assembly elections.

Some writing panders towards the Voter Decides School, in which genius pundits somehow manage to analyse a complicated electorate as if it were actually one rather stupid and predictable person.

Another set of writing veers towards the I Told You So School, in which even a seven-eighths majority or whatever the AAP just won in Delhi can't change anyone's mind, and it just reinforces the point that they had been making for ages -- that the government needs to reform more, or reform less; or Rahul needs to step up, or Rahul needs to quit; or that voters want Growth, or that they want Governance, or that they want Freebies.

The truth is that the AAP's victory, like all successes, had many, many fathers. Let's take them one by one.

First, the Congress. The math is stark: the Congress's vote-share collapsed, and the AAP mopped up every single precious percentage point. Good candidates lost, people respected in their neighbourhoods, people with name recognition and track records.

They lost because the Gandhi Congress is now a massive liability. Party posters on the street had already made that clear: they had the tricolour, the candidate's face -- but you really had to squint to see Rahul and Sonia Gandhi up in a corner.

What does the Gandhi Congress do for any politician? It doesn't give them enough money to fight an election. It doesn't bring them ideological coherence. It doesn't assure them of committed volunteers. If the leadership are toxic vote-losers as well, why would anyone stay in the party?

Doubly so, when all that the Gandhi Congress has to offer its leaders is lonely humiliation, the opportunity to be martyrs for the greater glory of the Gandhi name.

The sight of Ajay Maken standing up on stage taking responsibility for mistakes that weren't his will unquestionably have convinced dozens of Congressmen to jump ship at the first available opportunity.

No organisation survives without accountability for decision-makers. No political party should take such a string of defeats without the people at the top making public recompense.

No organisation survives without accountability for decision-makers. No political party should take such a string of defeats without the people at the top making public recompense.

But in the Gandhi Congress is no public stock-taking, no contrition. On the day of the elections, as polls were closing, when Amit Shah was with his workers, and Kejriwal was with his workers, Rahul Gandhi was, very visibly, out with friends in a Vasant Kunj mall.

Anger at the Gandhi Congress will not vanish until its leadership -- Rahul, this means you -- are visibly seen as chastened. Anger will not vanish -- the Gandhi Congress will vanish instead.

In Delhi, its credibility as a political force has been destroyed in a few months, leading old Congress voters to hold their noses and vote instead for those they think are anarchists. To destroy a party more than a century old will be a truly magnificent achievement. Does Rahul Gandhi really want that on his conscience?

Second, the BJP. The hilarious sycophancy of its spokespeople, parading themselves arrogantly around television channels in an effort to insulate their High Command from one of the most disastrous electoral defeats in Indian political history, is a salutary reminder that in most of the ways that count, the BJP is the new Congress.

The scale of the 2014 Lok Sabha victory seems to have done two things: It had convinced the BJP that nothing other than Narendra Modi was necessary to win an election; and it led them to assume that the end of the Congress was necessarily good news for them.

The prime minister has promised a 'Congress-free India' -- my apologies, a Congress-mukht Bharat, I forgot that we live in the era of Hindi supremacy.

In Delhi, the BJP sees for the first time what a Congress-free India might really look like; and it is not good news for the BJP. Its votaries mocked those who pointed out, in May 2014, that the party had won a majority with only 31 per cent of the vote.

But those who live by arithmetic will die by arithmetic; and the numbers that were favourable to a BJP sweep when the Congress was a diminished force suddenly turn massively unfavourable to the BJP when the Congress is a negligible force. The biggest backer of the Gandhi Congress's future should now be the inhabitant of 7, Race Course Road.

The tragedy for the BJP is that it, in Delhi, was unable to pick up the vote that left the Gandhi Congress. This cannot be blamed on Kiran Bedi, or dissension in the local party.

The fact that it all went to the AAP suggest that the BJP simply wasn't able to convince Delhi voters that it was the best representative of the values that the median voter in Delhi desired of its government. If May 2014 is to be repeated or expanded upon, it will need the BJP to change that impression.

And don't tell me that Delhi is not India – that's a trite and pointless statement. Delhi is far more India's future than any other town; it is a place where the old set-in-stone politics of kinship has already almost entirely given way to a new agenda-based politics -- if one that is no less communitarian, no less 'populist'.

Those who imagined that Modi's appeal would not go beyond India's urban constituencies were wrong. It would be amusing if, in turn, the BJP made an identical mistake when evaluating Kejriwal's appeal.

Those who imagined that Modi's appeal would not go beyond India's urban constituencies were wrong. It would be amusing if, in turn, the BJP made an identical mistake when evaluating Kejriwal's appeal.

The question is: Has the BJP reached its electoral high tide? Is it the case that enough of India despises the blatant communal polarisation that is the party's raison d'etre, and that May 2014 was just because people had been fooled into believing that the BJP would defy its DNA?

Frankly, I think that is unrealistic. India's centre of gravity has indeed shifted right. The reason Modi swept UP was that his message -- the message that social inclusion, or 'appeasement', would come at the cost of prosperity, or 'governance' -- resonated with enough Indians to win, and more than ever before.

And this is fundamentally a right-wing message, and the AAP's success does not take away from that.

What the AAP's success does suggest, however, is that this is not yet completely Modi's country. He, and his party, have more convincing to do.

But we shouldn't assume that the lesson the BJP will draw from this is that they must retreat from the Hindutva that has not appealed to half of Delhi's voters. The lesson they could draw is that they need to preach more. They are a party of preachers, of pracharaks.

They may well imagine they need to convert more people, become more active Hindutva evangelists, underline the link they see between strong, religious nationhood and effective governance and prosperity.

Recognise, please that such a response is far more in their DNA than is a retreat from the values that drew them all to politics.

Either way, the BJP will have to come to terms with a monumental defeat. Modi has squandered his honeymoon on atmospherics, on photo-ops and foreign trips and fancy clothes. He had no opposition; the scale of May 2014 gave him unparalleled authority. That is now challenged. He is constrained.

Can he summon the strength to make bold economic reform of the sort he has avoided so far? Or will he instead draw the lesson from Kejriwal's success that a little light populism can go a long way? The Budget suddenly becomes an even more politically salient document than it was so far.

And finally, the AAP. A party that, without any institutional bench strength, without a long history, nevertheless picks itself up from a devastating loss, from being mocked across India, and comes back in this manner deserves respect.

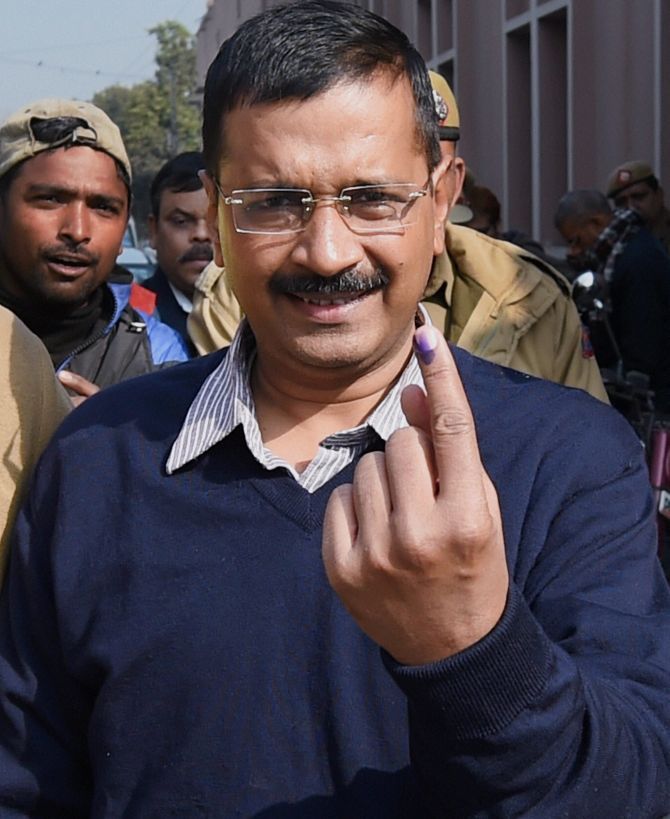

Arvind Kejriwal did that rare thing for an Indian politician: He publicly apologised. More: He said, persuasively, that he had learned from his mistake. That, more than anything else, convinced Delhi.

Kejriwal spent days and nights meeting people, going from seat to seat, even when his party was down and out. (Just read that and compare it to Rahul Gandhi, sitting in splendid isolation, apparently unable to change his mind or political approach.)

The AAP has a template for success now. It can take over the Congress-plus space. It can move into areas where the BJP currently dominates, but the Gandhi Congress is not an easy or palatable alternative.

Further, the Delhi success is bad news in places like West Bengal for the BJP, which has positioned itself there and in Telangana and in Tamil Nadu as the honest new outsider -- the local AAP slot, in other words.

Note that, quietly, Kejriwal has dropped his opposition to bringing in local-level political leaders with dodgy pasts. He has dropped his contempt for politics-as-usual. That will help his party expand through cannibalising the Gandhi Congress's increasingly disaffected local units -- exactly what the Bahujan Samaj Party, for example, did in UP and the Trinamool in West Bengal.

In UP last year, before the elections, I did see how Kejriwal had remarkable name recognition. But his name, then, was met with contempt. He had run from the battlefield, I was told; a man with no respect for power did not deserve it. He has been granted power again.

All of Delhi's vast hinterland -- Punjab and Haryana, but also, crucially, Bihar and eternally up-for-grabs Eastern UP -- will look to see how he uses it.

Only Kejriwal can screw this up for himself now. If he is actually patient, if he tries genuinely to fix Delhi's problems, then he can be India's Jokowi. Indonesia's new president parlayed a stint cleaning up the country's capital into national power.

This will mean compromise with power companies, compromise with the Centre, and an appearance of being a problem-solver. This is the last and most important way in which Kejriwal and his party have to transform themselves.

It is pointless to try and work out what the Delhi Voter 'wanted.' One can only note the facts: Many voters, plural, stopped voting for the Congress, and voted instead for the AAP. The important question really is: What lessons will the parties in question draw from this?

The Congress, I expect, will learn nothing. It will continue its smug decline, an arrogantly silent leadership still mystifyingly convinced that it is India's default party. Clearly, it no longer is.

The BJP: You can't be sure. It may become more truly itself, a party of social conservatism. It may become more inclusive, thinking Sakshi Maharaj and company are political liabilities. It may become more populist; it may take more risks.

It is not easy to work out which, because too much depends on the thinking of one man, and that too a man who has never before tasted defeat, let alone a defeat of this humiliating magnitude.

Finally, the attitude of AAP must be the most interesting. Have they learned? Can they keep the 15 good years of Dikshit's Delhi going -- and perhaps extend the acchhe din to the slums that kept their faith with the AAP in the darkest days of 2014?

If so, then we may have to redraw the electoral map of 2019.

REDIFF RECOMMENDS