'Now, as in Dara's time, it is far more important that power and structures of governance do not fall into the hands of fundamentalists,' says Rajni Bakshi.

A key moment in Indian history, enacted by the National Theatre in London, may offer insights on how to get beyond the increasingly polarising global discourse on faith, reason and Islam.

Pakistani playwright Shahid Nadeem's Dara is about Dara Shikoh -- a syncretic religious scholar, philosopher and heir-apparent to the Mughal throne in the mid-17th century at the height of that empire.

Dara found himself at the losing end of a bitter family struggle, was put on trial for apostasy and executed in 1659 by his younger brother Aurangzeb -- who went on to become the last major Mughal emperor.

In the early 20th century, as India moved towards freedom and sought to define the parameters of its nationhood, Aurangzeb's victory over Dara came to be seen as a decisive moment in the sub-continent's history. Many scholars and a wide range of political activists have equated Dara's defeat as a blow to religious pluralism and a victory for a narrow interpretation of Islam.

This is clearly Nadeem's reason for writing the play, which was originally produced by the Ajoka Theatre in Pakistan. The playwright sees not just his country but the Indian subcontinent being held captive by history. Thus, even today Sufis and moderate Islam are under attack, while more radical versions of Islam are being glorified.

Media reports have quoted Nadeem as saying that this play is 'a humble contribution to show that Islam is not about hatred or prejudice but instead is about love and harmony.'

While this is the central thread of the adaptation by Tanya Ronder, which opened on the South Bank of the Thames on January 27, it would be a mistake to see this as a one-dimensional account of good Muslim versus bad Muslim.

Dara's publicity primarily projects it as the story of a dysfunctional family. 'There is no limit to what families do to one another,' says the play's brochure, 'so much crueller than they are to strangers.'

Aurangzeb's lust for power is presented as being rooted in humiliation he suffers as a less favoured child while his father, Emperor Shah Jahan, dots on Dara. Aurangzeb's loathing for the Sufi tradition is deemed to arise from a prediction made by a Sufi saint that Aurganzeb will be the one to bring down the Mughal empire.

It is Aurangzeb's unloved and insecure persona sliding inexorably towards religious and political intolerance that emerges as the central tragic figure of the drama.

By contrast Dara, whose childhood is shaped by a loving family, grows up to be an avid explorer of India's diverse spiritual traditions while remaining a devout Muslim. Though his trial on charges of apostasy is primarily a ploy in the war of succession the play Dara deploys it as a device to pose the question that is as alive now as it was in the 17th century.

If you are a true Muslim, the prosecution asks Dara, what business do you have delving into Hindu scriptures and translating them into Arabic? By replying that Islam is not the only truth and the Hindu scriptures are also true, Dara seals his fate.

Dara's extensive spiritual and intellectual legacy has survived -- as an inspiration for those who see the subcontinent as a celebration of religious inter-mingling and as a challenge even annoyance to fundamentalists of all hues who want to build firewalls between religions.

Post 9/11 Dara's story has become important to the whole world, Nadeem said in a recent interview to the Dawn newspaper in Pakistan. 'We want to especially tell the Western world that Muslim societies are not just 'mullahs'. They are far more complex than that and especially through theatre this message can be given quite strongly.'

But the most crucial element of Dara's legacy is not about the overlap of religious traditions. Instead it is the richness of cultural streams that did not separate faith and reason as post-Enlightenment Europe did.

As the play's depiction of Dara shows, the real conflict is not between faith and reason, but instead between a inner quest for multiple truths versus literal application of religious texts. The former fosters open minds and an open society; the latter feeds insecurities and gives rise to fundamentalism.

This is what has kept the Dara legacy alive in modern day India. In the first week of February, the government of Uttar Pradesh announced plans to restore the neglected red sandstone structure in Agra that once housed Dara's library. This happens at the behest of a local civic organisation known as the Braj Mandal Heritage Conservation Society.

'This structure does not boast of power or royalty, but symbolises the spirit of Sulah Kul (universal peace), Din-e-Ilahi (syncretic religion) and later day secularism,' Surendra Sharma, president of the Society, was quoted as saying in Business Standard.

Therein lies a haunting question. Was Dara defeated because he was more drawn to mysticism and abstract learning than to the energies and skills required to hold and manage an empire?

As fundamentalist forces get closer to the mainstream of politics in many parts of the world, those who are inspired by Dara's legacy will have to apply this question to themselves. It may be a fatal error to hope that the beauty of syncretic cultures is sufficient to ensure their survival or in some cases revival.

Now, as in Dara's time, it is far more important that power and structures of governance do not fall into the hands of fundamentalists.

Rajni Bakshi is the Gandhi Peace Fellow, Gateway House.

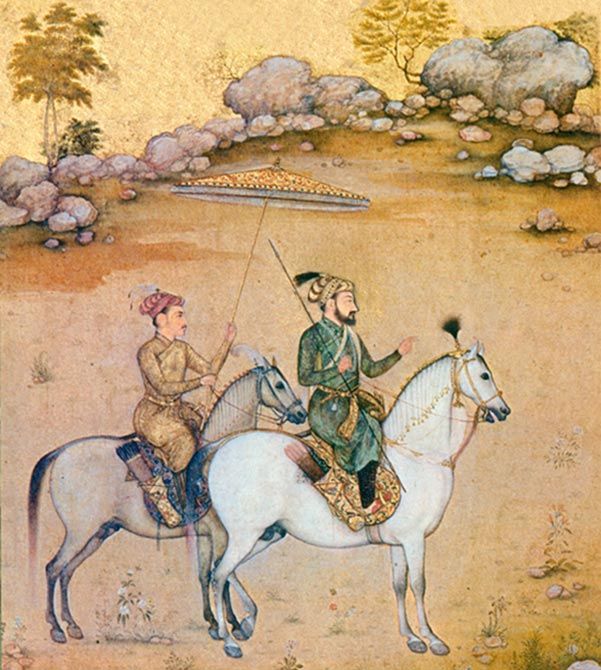

Image: Shah Jahan with Dara Shikoh. Painting by Govardhan. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.