The festering dispute over the accession of Jammu and Kashmir stands out as one of the world's most volatile fault lines that divides regions, countries, societies, communities and ethnic groups, notes Mohammad Sayeed Malik, the distinguished commentator on Kashmir affairs, on Sheikh Abdullah's 39th death anniversary.

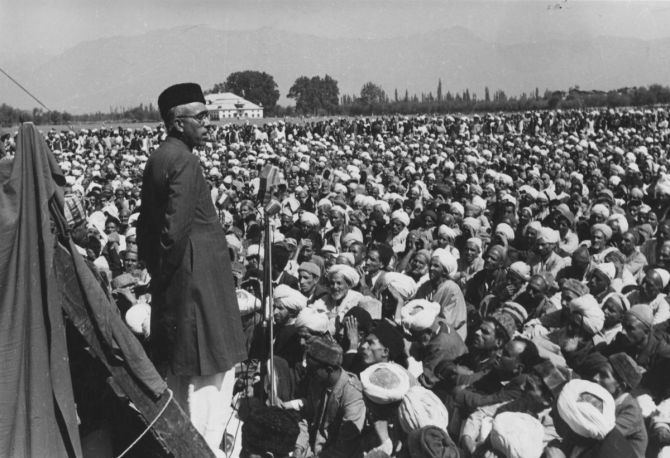

Measured by its cascading global geopolitical repercussions, the accession of Jammu and Kashmir with the Indian Union in 1947, against the run of events in the blood-soaked partition era, is undoubtedly the most visible milestone of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah's over half a century-long unparalleled stewardship.

The Sheikh's admirers revere him for his 'momentous achievement' while his critics revile him for his 'monumental blunder'.

The crux of the Sheikh's deeply embedded imprint, however, lies somewhere between these two extremes of conflicting perceptions.

On his 39th death anniversary, September 8, the festering dispute over the accession stands out as one of the world's most volatile fault lines that divides regions, countries, societies, communities and ethnic groups.

Between 1947 (when accession was the elixir of his roaring popularity) to this day in 2021 (when his grave needs armed protection against the threat of vandalism by anti-accession forces), the political landscape in and around Sher-e-Kashmir's motherland has drastically changed.

To be fair to the man, despite harsh turns and twists in his turbulent personal and public life, the Sheikh liked to flaunt his vindication in the accession battle. His autobiography acknowledges it in great detail.

However, recalling the Sheikh's accession saga which makes him a 'hero' and/or a 'villain' at the same time, inevitably leads to a parallel story from the opposite end.

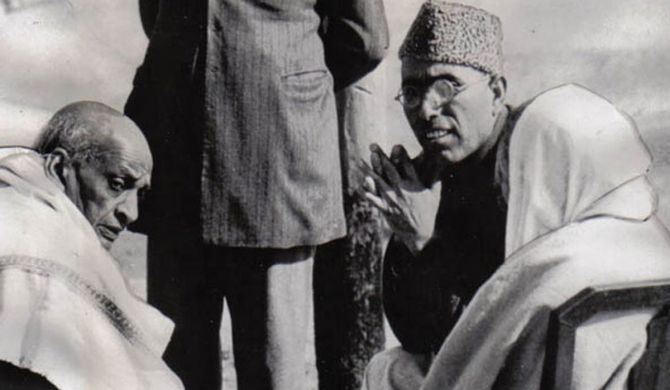

Sheikh Abdullah and Mohammad Ali Jinnah had so much uncommon between them that it is indeed impossible to visualise how the world around us would be today had there been anything common between the two, at all.

During the best part of his public life, the Sheikh despised Jinnah's politics and his ideology.

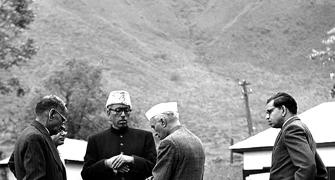

Yet the former's behaviour betrayed a hidden yearning in the Sheikh's psyche for emulating Jinnah's persona: Jinnah was 'Qaid-e-Azam' and 'Baba-e-qaum' to his own people, the Sheikh adopted both titles with unabashed relish; Jinnah's trademark Western style dress became Sheikh's choicest outdoor attire and even the 'Jinnah cap' tantalised him.

This intriguing unacknowledged co-relation between the two inveterate foes begs the question: Did Jinnah's arrogantly 'correct' style evoke some kind of envious admiration in the Sheikh's mind and impel an urge to be seen like him?

Retrospective profuse admiration for Jinnah in the Sheikh's autobiography Atish-e-chinar supports such a conclusion.

After over seven decades of the 1947 accession its historical discourse remains alive and kicking.

The issue continues to be revisited even across the border in Pakistan.

Closer scrutiny of Jinnah's role is a notable feature of the emerging narrative.

History's unanswered questions are being revived to find the missing pieces of the jigsaw puzzle.

How was it that Jinnah lost Kashmir from, what he used to claim, 'in my pocket'?

How did Jawaharlal Nehru manage to turn the (communal) logic of Partition on its head and snatch a Muslim-majority state next door to Pakistan?

Regarding the first, there are two mutually conflicting accounts:

1. Jinnah was kept in the dark while others around him planned and launched the tribal invasion on Kashmir in October 1947 and

2. Jinnah was very much in the loop, but his overconfidence proved fatal for his cause mainly because he miscalculated the 'Sheikh Abdullah factor'.

By the time Jinnah realised his blunder it was too late.

The British commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army refused to obey Jinnah's orders to commit regular troops along the Kashmir front in support of the retreating tribal invaders.

More importantly, the wisdom behind launching of the tribal invasion is now being questioned in Pakistan more openly than before.

A significant section of political analysts as well as military strategists argue that the 'equilibrium' that prevailed from August 15 to October 22, 1947, primarily because of Maharaja Hari Singh's indecisiveness, provided crucial space for Pakistan to keep the vacillating ruler engaged and work on the Kashmiri popular leadership.

The Sheikh's autobiographical version is that emissaries from Pakistan came with closed mind and were not open to argument. They threatened to use 'other means' to annex Kashmir.

Also, the Sheikh's emissary, G M Sadiq was still engaged in talks with Pakistani leaders in Lahore when the tribal raiders stormed into Muzaffarabad.

As the course of war changed with the hurried conclusion of the accession and consequent arrival of Indian troops in Kashmir, Jinnah ordered General Douglas Gracey, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army, to invade Kashmir, but he invoked the rider dictated by London against involvement of British army personnel in any war between the newly created dominions of India and Pakistan.

The fact of the accession backed by popular support had materially changed the international status of Jammu and Kashmir from an independent Maharaja-ruled entity to technically an integral part of the Indian Union.

The tribal invasion had the immediate effect of Sheikh Abdullah's total disengagement from Pakistan and unreserved alignment with India.

Soon after the dust began to settle down, the Sheikh encountered unforeseeable 'betrayal' from his rear, but in the end he managed to re-emerge with a political profile that was vague enough to allow him to be again seen on the right side of the accession.

Recorded historical evidence brought to light recently reveals that Nehru had been tipped by Lord Louis Mountbatten about preparations in Pakistan for a tribal invasion on Kashmir.

Military and intelligence agencies in both countries at that time were effectively controlled by the British.

Both Nehru and Sardar Patel had emphatically told Mountbatten that Kashmir was critical to India's security.

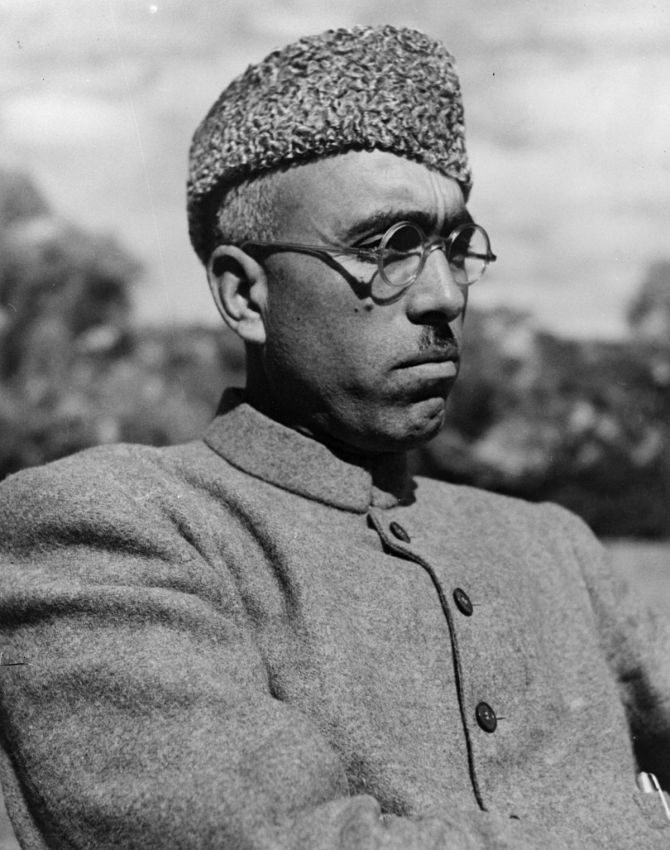

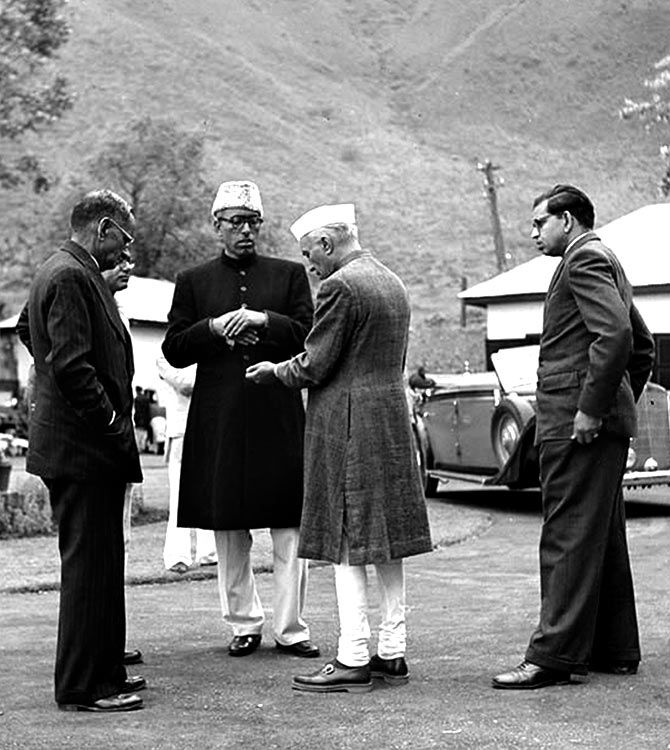

Nehru is said to have sensed well in time the need for enlisting Sheikh Abdullah's active participation in future proceedings in order to safeguard India's interests in Kashmir vis-a-vis Pakistan.

A beleaguered Maharaja Hari Singh, even with Indian military support, was considered to be no match to the challenge.

That is why Nehru remained adamant on securing the Sheikh's endorsement fo the mkaharaja's request for military intervention, following the accession formality.

Eventually, Nehru did not have to exert too hard to secure the Sheikh's backing as he found Barkis is willing.

Accession remains the live-wire of Kashmir politics in all its forms and at all levels. It still is the ultimate dividing line in the arena.

Long before George W Bush voiced his infamous dictum, 'If you are not with us you are against us', accession politics given birth to this thumb rule for identification of 'friend' and 'foe' in this part of the world.

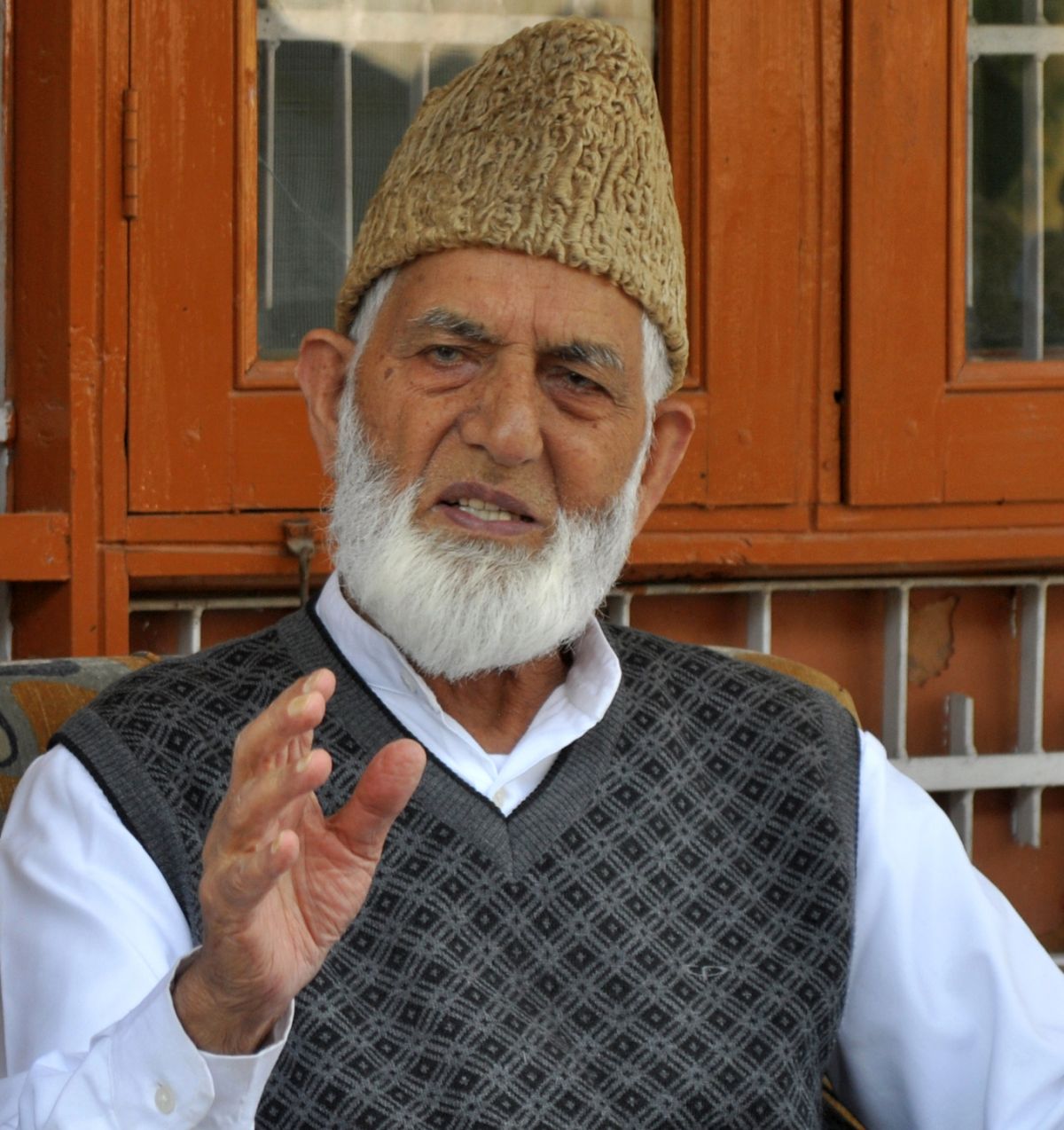

Coincidentally, Syed Ali Shah Geelani, who died on September 1, 2021, symbolised the 'other extreme' of the accession polarity.

Like everyone else, Geelani, though gradually gaining prominence within the anti-accession camp, could never measure up to the Sheikh's public or physical stature.

Geelani, like a few others across the board, gained prominence only after the Sheikh's demise in 1982.

His quest for occupying the top irreversibly pushed him to the extreme political line in Kashmir politics.

Meanwhile, the accession saga survives as an evergreen part of the Sheikh's otherwise fading legacy.

R I P Sheikh Saheb!

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com