January 24, 1966 was the day Indira Gandhi was sworn in as India's third prime minister.

It was not an easy elevation to the office her father Jawaharlal Nehru had dominated for 17 long years.

Soon after Lal Bahadur Shastri's untimely death in Tashkent on January 11, 1966, the Congress party's old guard -- men like K Kamaraj, S K Patil and Atulya Ghosh -- backed Indira Gandhi against Morarji Desai, because they felt she would be more amenable to their demands and dictates than the stern and uncompromising Desai.

It was a judgement they would come to rue.

Just three years later, the woman, many in the old guard had once described as 'gungi gudiya' (dumb doll), would split the Congress, marginalising men like Kamaraj, Patil, Ghosh and Desai to the sidelines of Indian politics, as she cast the party in her own image.

Indira Gandhi was a leader like none other in India's post-independence history.

Usha Bhagat, who worked closely with her, recalls those heady days, when Indira Gandhi took charge, 40 years ago:

Shastriji's sudden death not only shocked the nation but also created uncertainty once again about the political future of the country less than two years after Panditji's death. This led to frantic political activity and a tussle for leadership, with Mrs Gandhi emerging as the prime minister. Regarding Mrs Gandhi's frailty, Katherine Frank writes: 'Though she often appeared frail and vulnerable, there was a hard and resilent core within her: she never collapsed.'

'Indira Gandhi was uncomfortable with educated people'

When Mrs Gandhi was elected prime minister, I went to congratulate her. I still remember that her face had a glow of an inner radiance. Perhaps for the first time she felt a sense of personal fulfillment. Most of her life she had done things for others or because of others, which had constrained or restricted her, without giving any fulfillment. Perhaps she suddenly felt free of those feelings.

In the first decade that I knew Mrs Gandhi, she was frequently moody, irritable, and often ailing. When she became the prime minister and faced challenges on her own, I feel this brought out her potential, creative energy, and inner reserves, and she gained in confidence and her sense of well-being was enhanced. As (biographer) Mary C Carras writes: 'It (the job) also offered her a degree of challenge that suited her personality and the opportunity to exercise skills and develop capabilities - thus satisfying (her) need for self-fulfillment. I remember the first speech she had to broadcast on All India Radio soon after becoming the prime minister. She had to go to the radio station to make a live presentation. The time had been fixed. The speech was still being finalised and was being translated into Hindi and typed. Mrs Gandhi left for AIR with some pages while I waited for the last pages to be typed and then rushed to the station afterwards. While the discussions were about literature and related matters, it was amusing to note that a number of these intellectuals seemed quite desirous of state patronage. It was refreshing to see rebel streaks in two young poets, but one of them, over a period of time, cultivated a person in the prime minister's personal office and eventually managed to become an member of Parliament. Excerpted from Indiraji: Through My Eyes by Usha Bhagat, Penguin Viking India, with the publishers' permission. Ms Bhagat was a kindergarten teacher in the little school where Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi came to study. She gave up her job to become Indira Gandhi's secretary and worked closely with her for about 31 years, attending to her personal and official matters. She witnessed Indira Gandhi's happiest and saddest moments and had a close, personal view of the life of India's only woman prime minister. She lives in the capital and has been associated with the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the Indian Council of Cultural Relations, Republic Day celebrations and more. Image: Reuben NV Images: India's Iron Lady

That Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit also had ambitions in this direction is revealed by her sister, Mrs Krishna Hutheesing. On learning of Shastriji's death she writes:

My sister cancelled her lecture tour and came tearing home from America. Having been Indian ambassador to Russia, the US and a high commissioner in London and world figure because of her presidency of the United Nations, I believe, she thought she had a chance. But

Mr Kamaraj (K Kamaraj, head of the Congress party at the time) had not even thought of her, because though she was popular abroad, she had been away from India too much

His (Kamaraj's) choice fell on Indira

He felt she was the one who would be the most acceptable to the Indian people and therefore would be a unifying influence.

Mrs Pandit's greeting to Mrs Gandhi was also tongue in cheek: 'Mrs Gandhi has the qualities. Now she needs experience. With a little experience she will make as fine a prime minister as we could wish for

She is in very frail health indeed. But with the help of her colleagues, she will manage.'

The Early Days

Mrs Gandhi as well as the rest of us took some time to adjust to the new work and responsibilities. There were new challenges, and confusion, yet excitement too. For the first couple of years, speech writing was quite a bugbear. Besides the material supplied by the office, a few friends were asked for their suggestions and ideas as well. Being fastidious and meticulous, Mrs Gandhi used to work long hours late into the night giving shape to the speeches.

Gradually, she became more confident both in handling her affairs as well as in writing her speeches. She would take less time and became more relaxed. Of course, when Mr (H Y) Sharada Prasad took over as the information advisor, he became the mainstay in this sphere and used to work diligently and unobtrusively in preparing the drafts.

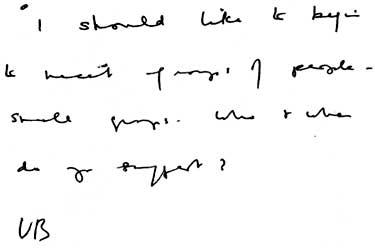

In the early years of her tenure as prime minister, when the burden of politics did not hang so heavily on her, Mrs Gandhi wished to meet interesting groups of people, to interact with them and to learn about their problems.

She added: 1. Bright young people -- mixed artists, students, 2. Social workers, 3. Lawyers, senior citizens, and 4. Architects.

When she met a group of Hindi writers, I was a little apprehensive. The spoken Hindustani of the Nehrus was excellent, but Mrs Gandhi had not done much reading in Hindi, unlike English. That is why, after becoming the prime minister, for some time she was not very fluent in reading speeches written in Hindi. (I was audacious enough to suggest that she scan Hindi newspapers as well.) However, the dialogue with the Hindi writers went off very well.

Photographs: India Abroad Archives and from Indiraji: Through My Eyes

Mrs Gandhi comes to power