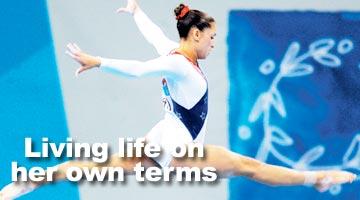

Even before the Olympic trials of 1996, Mohini Bhardwaj started living on her terms, and for much of her teenage years, on her own. When 13, she moved out of her parents home in Cincinnati, to Florida, where she trained under and temporarily lived with ace coach Rita Brown. When 16, Brown sent her to Houston, where she trained under Alexander Alexandrov, former head coach of the Soviet gymnastics school, and started staying in her own apartment. The freedom was a little more than she could handle. She started having parties and letting people crash on the floor. She drank frequently, and smoked a lot.

By her senior year of high school, Mohini had a bit of a reputation, but she was so gifted an athlete, and her grades continued to be so good, she got by, making the national team for the sixth year in a row and finishing third in the US Championships. But her run ended at the 1996 Olympic trials, when she placed 10th.

"In her mind, I don't think Mohini thought she could make the team," said Brown. "She had the talent. She had the skills. But I don't think she had the belief in herself. She wasn't confident. Her self image was 'I'm good, I'm great, and I made it here.' That's what her final goal was. At that point in time, I had coached three athletes to the Olympics. You can see in their eyes, before they compete, the desire to be on the team. I didn't see the desire in the eyes that I saw this time [at the 2004 Olympic trials] in California."

That could have put an end to her Olympic aspirations, but it put them on hold. Although somewhat burned out from 1996, Mohini joined UCLA, whose gymnastics program is led by head coach Valerie Kondos Field.

Field confronted Mohini about her reputation as a partier, which Mohini admitted to, but nothing changed in her freshman year.

Mohini gained 10 pounds (she's 92 pounds now) and often stayed out all night. Finally, when she lied to avoid an end-of-semester practice -- she was too hungover from the night before -- Kondos Field found out and threatened to kick her out of the team if she did not change her ways.

From that point on, everything changed. She set multiple records at UCLA while leading the Bruins to successive NCAA titles. She received a Honda Award for athletic and academic distinction. Although the transition from elite, or international level, gymnastics to the collegiate level is considered a dropoff for many gymnasts, Mohini did not treat it that way.

From that point on, everything changed. She set multiple records at UCLA while leading the Bruins to successive NCAA titles. She received a Honda Award for athletic and academic distinction. Although the transition from elite, or international level, gymnastics to the collegiate level is considered a dropoff for many gymnasts, Mohini did not treat it that way.

"You'll find a lot of people water down routines once they transfer from elite to NCAA. But Mohini was one gymnast who continued to train and perform at a high level," said Korotky. "She performed a Yurchenko Double Full in college, which is one of the most difficult moves, even today, and it's the same vault she performed at this year's Olympics. Mohini continued to go above and beyond what was called for, which is one reason she had a big following during her career."

Although she opted out of competing for the 2000 Olympics, she decided in 2001 that she would give Athens a shot. For someone in the NCAA it's not a small decision, as formats and levels of intensity are different. But in 2002, at her first serious competition, she fell and dislocated her elbow.

The injury proved serious. Soon after that, she announced retirement.

"I worked at a bar for a while, delivered pizzas," said Mohini. "Not really happy. Kind of bored. It felt good to make a little money, but hanging out isn't as much fun as it seems. I didn't feel I was accomplishing something every day. With gymnastics you are used to accomplishing something constantly."

In 2003, with less than a year to go for the Olympics, she decided to give it another shot. Her announcement was met with skepticism.

"Many people wrote her off after 2002," said Korotky. "Even after she first came back, many people doubted her -- not because of who she was, but because for anyone to take time off and return in that final stretch is extremely hard."

He paused.

"It really is remarkable. She did an amazing job. Fans realize that. They knew the struggle she had gone through, and what she had to fight back for."

But the struggle was still underway when Mohini realized she could not make ends meet without additional funding. Her father Dr Kaushal Bhardwaj supported her for many years, but Mohini says she didn't want that to continue. She held down several jobs at the same time, while attempting to train -- an impossible juggling act for an Olympic candidate, not least for one playing catchup.

Her friends at the gym decided to organize a raffle on her behalf. One friend decided to drop by the home of actress Pamela 'Baywatch' Anderson.

Anderson, a onetime gymnast, listened to the story and visited the gym while Mohini was training. The two chatted and bonded over vegetarianism (Anderson is a spokesperson for PETA). At the end, Anderson promised Mohini $25,000 in funding.

That made the difference. With a strong performance at the US National Championships, Mohini was invited to Anaheim for the trials. By then, the story of her fight to return was assuming mythic proportions. She was cheered every step of the way as she competed to qualify. Anderson famously sat ringside, holding up a 'GO, MO!' sign.

When the US Olympic team was officially announced, hers was the sixth and final name.

THERE are hundreds of active gymnastics clubs across the country, in places like Fruitland, Idaho and Prattville, Alabama. Every year, a generation of pre-schoolers, some as young as two, get enrolled into beginners classes, their parents keen to channel their child's boundless energy and elasticity and hoping that they have a little Mary Lou Retton or Bart Conner on their hands.

However, gymnastics is also an overwhelmingly white culture, something that could be witnessed firsthand during the T J Maxx tour, at least in the stands. Four performers on the floor were people of color: Mohini, Raj, Annia Hatch and Shenea Booth. But the fact that two Indian Americans made it to the Olympics is inexplicable, given that so few people from the Indian community pursue the sport, compared to, say, tennis.

"There are really not that many Indians in gymnastics," said Sonya Nair, a student at the University of Texas who left the sport in her early teens. "I can't remember one that I ever saw at competition."

Although Raj Bhavsar wasn't alone in his early forays into gymnastics -- his brother before him and his cousins had also participated -- his mother could recall only one other Indian American who became competitive.

"We don't think about sports," said Surekha Bhavsar, Raj's mother. "We only think about how we can excel in education. Simple things like when we hear other parents say, 'My son's going into journalism,' and others say, 'What's he going to do with journalism?' I don't' think it should be like that. They should explore whatever they want to. We have so much opportunity here, besides being doctors and lawyers and engineers."

Gymnastics is an exceedingly demanding activity, one that can consume almost every hour outside the classroom and sometimes classroom hours as well. For several years, Nair said, she spent four hours every day after school in training, and woke up at 5 am on weekends to prepare for competitions, many of them out of town.

When 8, she became Texas state champion, climbing up the rungs of competition until she was a Level 9. When she was in 8th grade, she started training for Level 10, the last level before a gymnast attains Elite, or international level, competition.

But the hours were wearing her down. When she injured her wrist, she decided she would discontinue gymnastics and try her hand at easier activities like cheerleading and dancing. Her decision wasn't taken easily by her parents, particularly her father, Bas Nair, a marathon runner and onetime member of the Indian national cricket team who felt his daughter's greatest successes were around the corner.

"But it really was a relief," said Sonya. "I was reaching the point in time when friends were going to movies or hanging out after school, so I was excited."

Part III: 'She can't have a tattoo'

Pictures: India Abroad Person of the Year 2004

Read about:

India Abroad Person of the Year 2003

A community honours one of its own

Photographs: Getty Images

Image: Rahil Shaikh