'Which movie has been about love between castes?'

'In Ek Duje Ke Liye, the divide was between a non-vegetarian north Indian family and a vegetarian south Indian one; in Amitabh Bachchan's films, he's poor and the heroine's rich.'

'But which caste do the hero and heroine belong to? No director has dared talk about that.'

Jyoti Punwani examines the relevance of Sairat, the hit Marathi film everyone is talking about, in today's times.

Sachin Lokhande, 35, a Buddhist, married his Muslim girlfriend earlier this month. He had waited 12 years for both families to agree. The girl's mother came around when she saw him study engineering and take up a job. But it took Nagaraj Manjule's movie, Sairat, to convince Sachin's parents.

This is the third case of a change of heart brought about by Sairat, the recent Marathi film about inter-caste love in a Maharashtra village.

The other two cases have passed into folklore already: The auto driver who had been hunting for his sister in order to kill her for marrying out of caste but, after seeing the movie, wants to check on her to see if she needs anything; the Maratha parents who want to bring home their estranged daughter who had eloped with her Matang boyfriend.

These stories are related by a group of men and women in Ramabai Nagar, the Dalit colony in Mumbai, which sprang into the limelight in 1997 when police opened fire outside it on Dalits protesting the desecration of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar's statue. Eleven people died in this tragedy.

The firing is not mentioned in the long discussion about Sairat. But identification with the unmentioned but all-pervasive caste equations depicted in the movie comes through clearly.

Be it the village Patil's well where the rest of the villagers may swim only at the Patil family's pleasure; the Patil's privileged kids with their bikes and their birthday bashes where the entire village is invited; and, last but not the least, the hero's home in the 'lower caste' basti far from the main village -- implicit in these locales and scenes, Dalits in Ramabai Nagar tell you, is the power structure that exists in villages even today.

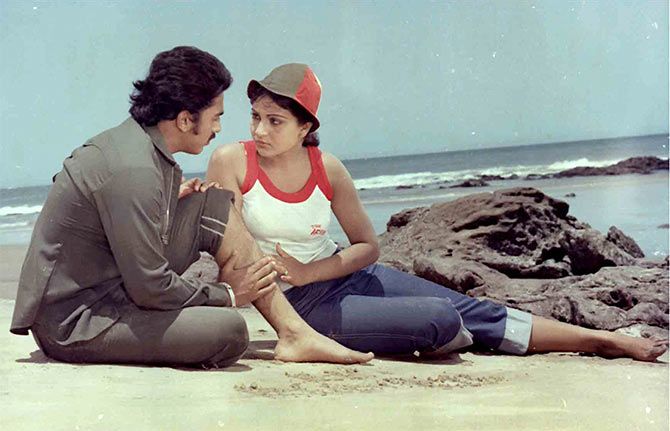

This structure was depicted starkly in Manjule's debut film, Fandry (2014). But, in Sairat, caste equations are woven into a love story, something that has rarely been done before.

"Which movie has been about love between castes? In (the Kamal Hassan-Rati Agnihotri starrer) Ek Duje Ke Liye, the divide was between a non-vegetarian north Indian family and a vegetarian south Indian one; in Amitabh Bachchan's films, he's poor and the heroine is rich," points out Yogesh Kamble of Muktyaan, a Leftist cultural organisation. "But which caste do the hero and heroine belong to? No director has dared talk about that."

The recently released Masaan, which was centred around caste, was appreciated by the critics but it wasn't a hit.

Bimal Roy's classic, Sujata, dealt with the caste divide upfront, but today's generation aren't familiar with the 1959 tale of a Dalit girl who attracts the affection of a Brahmin boy.

Even in Sujata, it was only the heroine's act of donating blood and saving the life of her Brahmin adoptive mother that made the latter shed her prejudice and allowed Sujata to marry her Brahmin admirer.

In Sairat, there is no such dramatic deus ex machina to redeem the inter-caste union. The couple do so on their own.

The Patil girl and the fisherman's son, on the run from her father, have to deal with the ugly reality of life in a new city with no money and no friends. The city may provide them with safe anonymity, but it also makes relentless demands.

That they finally succeed is a testimony to the potential such marriages have, says Nilesh Ahiwale, The film shows that those who decry inter-caste marriages are wrong. Such marriages can work, and must be accepted.

This interesting new angle on the doomed union of Sairat's inter-caste couple was shared by all the Dalits Rediff.com interviewed. Tata Institute of Social Sciences student Pawan Salwe puts it well: "Love alone can destroy caste, and it is only by destroying lovers that caste can triumph."

Not everyone agrees. A student pursuing a PhD at IIT-Bombay, who does not want to be named, says gloomily, "It's not so easy to wipe out caste. If casteist feelings persist in a highly educated environment like IIT, it will take 100 years for casteism to disappear from the larger society."

But the rest would have none of his pessimism. "See how much has changed since Independence, in just 60 years," counters Kishore Kardak, who married out of caste against his parents' wishes. He has seen Sairat five times already.

"There has been exponential change with regard to caste and this will continue. Sairat itself is part of that (change). Would such a film be so popular if people's mindsets weren't changing?" Kardak asks.

If Ramabai Nagar's Dalits found the ending full of hope, members of Vidyarthi Bharati, a student organisation that works on issues of caste and gender, liked it for its realism. "What other ending could there have been? Like 'they lived happily ever after'," asks Vijay Singh, son of a Punjabi father and a Gujarati mother, incredulously.

"The young couple had worked hard at their relationship. They finally stabilised it and managed to get everything going for them. Where was the problem with their marriage?" asks Rahul Gharat, a student at the J J School of Art. "It was just caste. This film will make opponents of inter-caste marriage question themselves: What kind of casteism is this? The silence, especially at the end, gives viewers space to think."

"A happy ending wouldn't have been realistic," says Smita Salunkhe, who has just graduated from TISS. "What would we have got out of it? We'd have left the theatre thinking all is right with the world. It would have strengthened the false belief of those people who say caste discrimination no longer exists. It is the ending that makes us question the power of caste that makes people blind to their own child's happiness and even to her right to live. This happens all the time."

This happens, it is real, and it is about us.

This feeling of identification that the film has created among viewers could be the main reason for Sairat being the all-time hit it has become, grossing Rs 55 crores (Rs 550 million) in the 18 days since its release, a record for Marathi films.

The identification is at various levels.

There is the rural setting. For Marathi-speaking Mumbaikars, their village is their second home. They connect instantly to the film's typical village scenes: The cricket match with its garrulous commentator and the politician who graces it; the use of rustic language and words such as 'zingat' (to go berserk, but in a positive way; the reference here is to one of the popular songs in the movie, Zing zing zingat). "My grandfather used to use it," recalls Sumit Kasare.

There is a rather 'human' hero, the kind who gets bashed up all the time, who remembers to remove his watch and wallet even as he rushes to dive into the well where his dream girl is swimming.

But ultimately, the identification comes from the feeling of recognition that this is our story finally being told. Says Pawan Salwe, "I can't put my finger on it, but never before has there been such a realistic depiction of the yearnings of young people. In urban areas, whether they hail from villages or from the city, youth are constantly seeking themselves. They can identify totally with this film."

These record-breaking collections could not have come from Dalit viewers alone. Non-Dalits, even middle-aged cinema goers, have felt compelled to see Sairat. Sunil Borkar, who works in the sugar cooperatives federation, could immediately connect with the film, even though he felt that the village Patil is not as powerful today as the film makes him out to be.

IT professional and AAP member Dhananjay Shinde, who rarely sees films, compares Sairat to the ideal Marathi meal, one that contains the panch pakwan -- all the necessary tastes. "It has all the raasas (emotions)," he says, "from ecstasy to sorrow, from entertainment to realism."

The film has the 40-year-old Shinde reflecting: "Had I, as an 'upper caste' man, dared to do what the Patil heroine does, I'd have been punished too on a scale of one to 10, with 10 being 'honour killing'."

Manjule's taut, stark and understated Fandry won five national and international awards but was not seen by even half the numbers thronging Sairat. The many songs and romantic scenes that dominate Sairat's first half, seen by some as a concession to commercialism, are possibly another reason for its mass appeal.

But most viewers see it as integral to the film. Says engineering student Ashish Gaekwad, who plans to show the film to his parents on his laptop when he goes back to his village which has no theatre, "The heights of love depicted in the first half were necessary, else the sharp fall into harsh reality in the second half wouldn't have had such an impact."

Sairat was marketed like any blockbuster, with a promo that left viewers eager for more, songs being released before the movie, continuous publicity on television and a simultaneous release in 800 theatres.

Would it have had the same impact without the songs and all this blitz?

Other movies released with as much fanfare haven't fared half as well. Could it be because the stories of handsome rich city heroes and heroines, unlike Sairat's hero and heroine, have little to do with viewers' lives?

While the hero and his two friends (all of whom, typically for poor village youth, share one mobile), are immediately likeable, it is Sairat's heroine, Archie -- "bold without losing her femininity," as one fan described her -- who is the star here. A Class 9 school girl who has never acted before, she scored 80 per cent in her exams even after acting in the film, you are told. "Like the film, her personal life also proves elders wrong -- extracurricular activities do not affect your academics if you are determined to do well," says Sachin.

The Akhil Bharatiya Maratha Mahasangh, annoyed at the negative portrayal of Patils in the film, is even more annoyed at the way the daughter of a powerful Patil has been depicted.

As Yogesh Kamble points out, the routine portrayal of the village Patil as a villain has never bothered them. "They are upset because a Patil girl is shown defying marriage norms."

But these Patil stalwarts are way out of sync with the thinking of their own youngsters. 'If you must have hobbies, be like Archie: Swim, ride a motorbike. Otherwise, 99 per cent of girls have just two hobbies: Make-up and break up,' goes one WhatsApp message from a young Patil.

Smita Salunkhe feels Archie is a role model for girls, given the way she takes the initiative every time without waiting for the boy to do so. So does Sarita Kardak, mother of two. "She is actually the hero, she loves the boy more than he loves her."

One of the objections to the film has been that it glorifies teenage love. Surprisingly, Ramabai Nagar's elders do not disapprove of this. "Love happens at the age of 17-18; in Mumbai, even sooner," says Dadasaehb Yadav.

After having listened to a two-hour long discussion on the film in which every angle was discussed -- down to the tee shirt worn by the toddler in the last scene -- Vishwas Kamble breaks his silence.

"Why are people criticising this film?" asks this grandfather. "Sunny Deol in Gadar goes into enemy country and braves all kinds of attacks for his girlfriend, though she is a Muslim! A Muslim, mind you! Why didn't people object then?"

"Here, just because a Patil's daughter is seen falling in love with a fisherman's son and fighting with her family for him, people are getting upset," says Kamble. "These two have the himmat (courage) to earn Rs 40,000 between them. Is that not admirable? But people's caste feelings won't ever end."

Kamble himself had taken his daughter away from Mumbai to the village to separate her from her boyfriend, who belonged to another caste. "But I found her phoning him from there all the time, so I had no option but to bring her back and let her marry him."

"This film won't spoil youngsters, it will reform them," adds a spirited grandmother. "They will realise what true love is, what setting up a home means. The girl is an example to follow. She knows nothing about running a house; but in the end, she manages house and office."

Tragic stories of doomed love have always been popular in literature and cinema. But in India, jaati (caste) has never been mentioned. Class has always been the culprit.

However, as the newspapers will tell you everyday, it is love across castes that remains forbidden and provokes the most bestial retributions and murders.

Sairat breaks this taboo, without blaming anyone, without preaching, without even mentioning the word. Could Nagraj Manjule have given birth to what one viewer described as 'the Sairat shaili (style) of film-making?'