'Mahesh Bhavana is a young man who is beaten up in the town's marketplace and who consequently pledges that he won't wear his slippers again, till he avenges the beating.'

'But Mahesh can't get his revenge that easily -- his punisher is off to a distant land. So what does Mahesh do? He waits. And the town waits with him. And we wait with him.'

'Maheshinte Prathikaram is one of those movies where I didn't know what hit me. I don't remember another movie -- at least in recent times -- that I surrendered to with such happiness,' says Sreehari Nair.

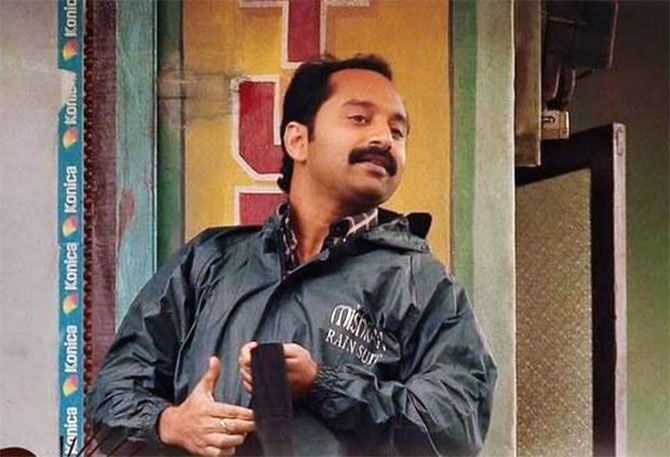

Is Fahadh Faasil India's finest young actor?

When he's waltzing through a role, Fahadh seems to be in complete possession of a luxury that only the screen's greatest icons and cricket's greatest batsmen have: That extra bit of time. For, when he is in his elements, nothing about Fahadh looks rushed or hasty. He buys that extra time from us. And we give it to him almost readily.

That's quite unfair, one might argue. So to make matters more 'balanced' perhaps, the universe unleashed another trick: It took away a part of Fahadh's hairline. A near-balding Fahadh could not be that interesting to look at, right? But Mother God, how wrong we were.

For, his steadily-thinning hairline only made Fahadh's eyes more prominent. And they are wonderful eyes; not just when they are angry or stunned or verily sentimental; but even when they are unsure or forlorn or merely surveying a room. Ghoulish eyes.

The prominent eyes are what truly give Fahadh Faasil his stride, and when in his stride with all that extra time he buys from us, Fahadh scorches the screen down. Very slowly.

However, this screen-scorching Fahadh is not the actor we meet in Dileesh Pothan's Maheshinte Prathikaram (The Revenge of Mahesh). As Mahesh, here, Fahadh doesn't need to bring himself to the forefront.

Instead he merges into the other elements in the frames: Into those around him, the furniture, the rustic backgrounds, the rituals, the deaths and his natural environment -- with the forests, the grime, and the mud.

Maheshinte Prathikaram is one of those movies where I didn't know what hit me and how certain scenes got their effects. But I also don't remember another movie -- at least in recent times -- that I surrendered to with such happiness; smiling through the entire length of its run.

In its core plot, Maheshinte Prathikaram may contain all the key qualities of a great short story. But in its rhythm, in the way it effortlessly and almost lazily leaps from one episode to another and from one character to the other, the movie is closer to the 'Creative Non-Fiction' style that Esquire magazine's writers of the '60s pioneered.

So imagine a star Esquire writer like Tom Wolfe getting to cover an assignment set not in the American South, but the Indian South -- specifically in Idukki, Kerala. Imagine the subject of his piece to be someone really plain and in his plainness, someone who is also great tabloid material: Mahesh Bhavana, a young man who is beaten up in the town's marketplace and who consequently pledges that he won't wear his slippers again, till he avenges the beating.

But Mahesh can't get his revenge that easily -- his punisher is off to a distant land. So what does Mahesh do? He waits. And the town waits with him. And we wait with him.

This is really NOT the story of Mahesh's revenge as much as it is the story of his waiting. And it is this wait that the director and his writer Shyam Pushkaran -- very much in the fashion of Esquire writers such as Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese -- turn into a sensitive portrait and a microcosm of small-town life.

Like those Esquire pieces, the movie alternates between the 'general' and the 'specific' -- one moment offering a vivid, dense view of the world that the piece is set in and in the very next moment condensing its essence to a set of motley characters.

The movie plays around with its central conflict and adds so many overlapping patterns that by the end, it subverts the conflict.

Debutant director Dileesh Pothan maybe that rarity in cinema: He is a poet of the commonplace. Pothan stages long takes with minimum fuss and mixes those with impressionistic, small edits. And the movie derives its basic pulse from that Domino Effect of a small confusion setting off a chain of bigger confusions, ruckus and even mayhem.

Incidental characters and happenstances at one point in the story turn into major characters and course-changing events, at a later point. And what might have come across as gimmicks in the hands of a showier director become pieces of breathless lyricism here.

Mahesh's pledge itself has mythical undercurrents: The kind that can only be taken in a really small nondescript town -- where people keep track of each other's affairs, remind each other of their schedules and need that 'rush' every now and then.

It's the kind of pledge that distances Mahesh from his natural gentleness and brings out the natural warlord side in him, makes him more focused, affects his psyche, and creates a premonition of apocalyptic spectacle in those who surround him.

Mahesh Bhavana, however, wasn't made for all of this. He is just an average photographer -- someone whose idea of 'clicking pictures' is essentially going through a series of fixed physical rituals: Chin up, chin down, eyes wide, shoulders down and all that jargon jazz.

If it's a really important photograph that you want him to click, he will draw open the curtains behind you -- in the manner of a self-styled wizard -- and reveal a set of corny wall-motifs. However, at a certain point Mahesh realises that the trick of photography was always around him, and yet he just didn't seem to take notice.

His father -- an old, worldly-wide man -- is the one who appraises him about this fact, just like he had once appraised Mahesh that it's not a 'Shop' that he works at, but a 'Studio.' In the course of the movie, this is not the only the discovery that's thrust upon Mahesh -- he also comes in contact with his feral side and Fahadh, here, carefully calibrates both those discoveries, not letting one eat into the other.

Fahadh's performance and his character Mahesh reminds you of that particular breed of men who might never raise their voice or their eyes, but if you wound them, will remember little details of that unfinished deal even when they are putting dog-food on the puppy plate.

Even as the men in the movie hold deadly grudges, get into petty fights and share cold handshakes without looking into each other's eyes, it's the women who turn on the heat very calmly.

Anusree who plays Soumya -- Mahesh's first love -- has such a radiant presence and a great camera face that she gives off two varying eccentrics with easy grace: You see her differently when she is by herself and then through Mahesh's eyes. She is naturally sensual and looks bewitchingly good when performing mundane tasks, like when she is just scrubbing the clothes on the stone.

And Aparna Balamurali as Jimsy -- the other woman who nurses Mahesh's sore heart -- has a terrific ping about her; a girl-woman who matches Fahadh gaze-for-gaze. She starts off on a rattle, stops to check if he's listening and after she has confirmed that he is indeed listening, picks up the beat again.

Also wonderful are all those nameless women characters who drift in and out of the scenarios, but all of whom come with their personal tricks and small strategies. Like Soumya's mother, who publicly states that her daughter will decide for herself who she wants to marry, and then privately at night in the bedroom, tightens the mental screws on her.

Maheshinte Prathikaram is actually a film about the inner strength in women that often masks the grand follies of men; a point that is driven home not through overt declarations but with glancing touches such as suggesting Idukki itself as a metaphor for 'The smart, shrewd woman' -- a rendering of that class of women who give their men the pleasure of barking orders from their armchairs while silently deciding for themselves what is 'correct' even as they peel the tapioca away.

It's not that the men in this movie are any less aware, it's just they are 'charged' by elements, different. There are two classic turns here. Alancier Lay as Mahesh's dear-old Babychettan is wonderful in the role of a man who maybe graying at the temples, but still has time for his antiquated theories about masculinity.

And Soubin Shahir as Crispin is proving to be the find of this decade; a Buster Keaton-like performer who manages to be funny while just being genuine and heartfelt. These men, like everyone else in the movie, go through their own lives while being the ideal foil for Mahesh as he tries to pull off his galoshes of pain.

The performers seem to 'perfectly understand' the short story-journalistic tone of the movie and approach their parts suitably, but Dileesh Pothan makes this a movie celebration -- he has different movie-stations running within one movie, activating each at his own pleasure. And he teams up with cinematographer Shyju Khalid to deepen the meaning of the scenes -- a little sleight of hand trick, always works for him.

Nature -- with its thick forests and streams and terrains -- is not captured here for its beauty alone, but as a silent chronicler of lives lived in a certain volume of harshness. To Pothan and his cinematographer, nature could be unjust, lulling, scary and surprising, all at once. When the men fight in dark-brown dirt, the camera tilts upwards slightly and you get the feeling that the lofty hills, like the Gods above, are maybe watching the showdown.

The medium may seem absent for most parts of the movie, but when it becomes self-consciously alive, it intensifies the effect of what you are watching on screen. Like, when Fahadh as Mahesh climbs the steps to his photo studio in a fit of joy, the camera is placed marginally overhead. It's a minor angle, but something that captures Mahesh's Cheshire Cat-like elation brilliantly well.

Dileesh Pothan and Shyam Pushkaran draw from their own experiences and memories of growing up in Kerala's small towns but they also pull back enough -- like seasoned journalists -- to ensure that the rhapsody doesn't get to them and their nostalgia is not scandalised.

So nothing seems half-done and nothing seems overstated: It is simply a magical union of out-of-breath reporting and imaginative storytelling where the titration is perfect and the scaling, just right.

Most importantly, however, the writer and director band don't see their characters as 'little people' who can be dumbed-down or played out for a few, cheap gags. The people in Maheshinte Prathikaram are all real people and they are smart and cunning and they all have their personal defence mechanisms, their staunch definitions of what is right and wrong, their individual take on big city trends, their party talents and their own tactics for survival.

You will be tempted to call Maheshinte Prathikaram 'a sweet and simple film' because it doesn't have big story-arcs or discernible character-growth patterns. But the movie is more than just that.

In its frankness, its directness and almost cliche-free flourishes, Maheshinte Prathikaram becomes a rare movie experience that is also incredibly generous -- both to the world it is set in and to the world it is made for.