The ordinary life lived in Pakistan is now a part of the Indian imagination thanks to the popularity of Pakistani television serials in India, says Mohammad Asim Siddiqui.

Pakistani television dramas first reached Indian households in the mid-eighties.

It was through video cassettes played on VCRs that dramas like Ankahi (1982) and Dhoop Kinare (1985) captured the imagination of many Indian families.

However, the appeal of these television serials remained limited to a particular section of Indian society, mostly middle class Muslims. Indian audiences would have to wait for many decades before a premier Indian channel would air Pakistani television content.

The dramas shown on Zindagi, the television channel launched by Zee Entertainment Enterprises in June last year, have become very popular in India. In the last few months, their viewership has increased significantly.

The commercial breaks in the serials are becoming longer and longer and more and more people are exchanging their notes on these programmes.

Some of the serials which have drawn the attention of Indian viewers include Humsafar, Zindagi Gulzar Hai, Piya Re, Khwahishein, Yeh Galiyan Yeh Chaubaara and Khel Kismat Ka.

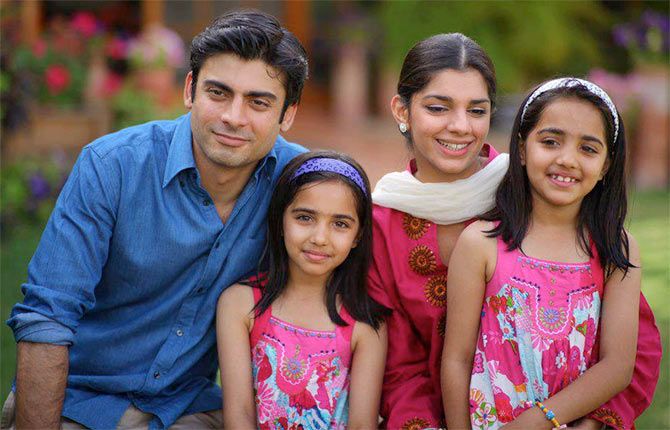

If it can be said that the ultimate destination of television stars is Bollywood -- more so of Pakistani artistes as Pakistan's film industry struggles to gain recognition -- then Humsafar stars Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan have already become a part of Bollywood.

Fawad Khan bagged the Filmfare Award for his debut performance in Shashanka Ghosh's Khoobsurat and Mahira Khan has been paired with Shah Rukh Khan in his next film Raees, to be directed by Rahul Dholakia.

One should not be surprised, if sooner or later, other actors appearing in these serials bag roles in Indian films.

Unlike regular soaps, these serials maintain an even pace and move towards a definite resolution within 20 to 25 episodes. With the exception of some serials like Khwahishein, most have avoided the endless recycling of situations.

The serials use easy-to-understand, conversational Urdu.

Words like dastbardar, sairab, bezar, taqaddus, khwar or wajood are definitely Urdu words but Indian audiences have always been exposed to the use of Urdu words through Hindi films, especially Hindi lyrics. One does not need to reiterate how well the Urdu-laden lyrics from the musical hit, Aashiqui 2, were received in India.

In some serials, a glossary of Urdu words appears helpfully on the television screen.

Except for the Urdu words imbued with religious imagery, most words are easily understood by even those who do not claim Urdu as their mother tongue but are exposed to Urdu in their daily life.

In fact, the language used in these dramas is close to Hindustani. It gives lie to the certainty that Hindi and Urdu languages have different identities.

Moreover, despite the apathy shown by different governments towards Urdu, the language is loved by the common people who are always eager to learn it. The language used in these serials poses no special problem of understanding for the Indian audience.

In recent years, Pakistan appears to have only a political and religious presence in popular imagination.

The image of Pakistan has been reduced to some dominant impressions which centre round the Taliban dressed in shalwar-kameezes with Kalashnikovs hanging on their shoulders or well-dressed diplomats and mustached army officers passionately expressing Pakistan's view on matters of strategy and polity.

At other times, an occasional Pakistani singer or chef makes an appearance on the Indian television screen.

Of course, Pakistani cricketers and cricketers-turned commentators remain the most familiar faces in India.

What is largely lacking is what American philosopher Richard Rorty calls the 'cosmopolitan conversation of human kind'. The ordinary life lived in Pakistan is rarely a part of the Indian imagination. In fact, the imagined life of the people living on the other side of the border is made up of these television images and political narratives.

The value of popular culture lies in foregrounding the ordinary and the commonplace. It puts the spotlight on the normative behavior, the everyday existence and the common worries and aspirations of people.

Sometimes the normative is brought out through its contrast with what is considered the idiosyncratic.

Until recently, novels and stories have served to familiarise people with far off places.

Our knowledge of the lesser-known parts of the world owed something to our reading of stories. People knew about Latin America from a reading of the novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Czechoslovakia from the work of Milan Kundera.

Those who did not read did not know anything about these places.

In today's image-centred world, television and the internet do the job of bringing the unfamiliar into our homes.

The value of Pakistani serials lies in making the unfamiliar appear so familiar.

Or, to put it the other way, the unfamiliar in this case was never really unfamiliar as India and Pakistan have a shared history and culture. The iconography in the serials appears very familiar.

Though there may occasionally be a serial about a sensitive subject like a child of rape (Piya Re), most of these serials centre round intrigues, revenge and those perennial themes of marriage and love.

As marriage between cousins is permitted in Islam, more often the serials show marital alliances between cousins. The familial relations and the extended families shown in the serials also do not appear to be very different to Indian audiences.

There is the inevitable presence of a scheming mother-in-law and prying relatives in these serials.

Interestingly, with the exception of Waqt Ne Kiya Haseen Sitam, a serial based on the events of Partition, most of the family dramas are silent on politics. There are no references to political leaders or the political problems Pakistan faces at present.

In one rare instance in Piya Re, the name Osama is mentioned to bring in a political reference. During a name-hunting session for a new-born child, when it is suggested that the child be named Osama, the grandfather of the child nonchalantly dismisses the suggestion saying, 'Osama cannot live anywhere except in Pakistan.'

The serials are set in an overall context where a religious worldview lurks only in the background.

Characters are not overtly religious though there may be an occasional religious character, like the father in Khwahishein. Though Pakistan has often been plagued by sectarian strife, the serials stay clear of the sectarian differences between the followers of Islam when it comes to the depiction of religion.

More than religion, it is the presence of feudal values is reflected in many of the serials.

The serials depicting the Westernised life style of middle class professionals introduce conflicts in an essentially modern set-up. Characters are identified by their Western clothing, Western manners and liberal use of the English language.

However, this Westernised lifestyle is supported by feudal values and the world of these characters is incomplete without their servants and maids doing the household chores in a routine manner.

Big and spacious houses with expensive furniture are very neatly cleaned by the domestic help, who are marked by their invisibility in the mental landscape of the feudal class.

There has always been an unholy alliance between patriarchy and feudalism.

The force of feudal and patriarchal values is most visible in Yeh Galiyan Yeh Chaubaara.

The family in this serial consists of a man who has a very devoted but frightened wife and two daughters. Both the daughters, especially the younger one, are also extremely scared of their father.

Rashdi, the central character in this drama, is always scolding his wife for not having a son, often threatening her with his power to pronounce talaq and not letting her speak.

Rashdi's actions -- insulting his wife and daughters all the time, getting his daughter married off to his servant as a sort of punishment for her, never showing affection for anyone -- show the ruthless and cruel face of patriarchy. He also does not find it strange to marry her daughter off to his 12-year-old nephew.

He wants to see his wife totally voiceless.

This serial, longer than most, is about authority and the lack of sufficient channels in patriarchy for its subversion. In fact, patriarchy comes under attack through the depiction of his character.

The device of showing rather than telling becomes important in developing an antipathy towards the authority wielded by the patriarch in the family.

The ironic end of the serial -- the birth of third-gender twins from his second wife and his becoming penniless -- appears forced, a kind of dues ex machina, in its attack on patriarchal-feudal values where property and sons are all important.

Patriarchal values are also very dominant in Khwahishein which shows the world of a poor family.

In this serial Ajiya, the central female character, aspires of leading an affluent life. In her desperation to move past her poor background, she spurns offers of marriage from two families of modest means and is duped into a relationship with an unscrupulous rich young man.

After running away from his clutches, she is a changed person. Now she offers her prayers regularly, does the household chores willingly, and also realises her mistake in not seeing the sincerity of the young men she rejected.

The good female Samaritan who escorts her safely to her home remarks: 'A woman should never forget her cloak and her four walls (the more alliterative Urdu expression chadar and chardiwari)' and that, among the men folk, 'a woman should trust only her father and brother'.

In another instance, Ajiya's younger sister also offers her a regressive advice: 'We girls are like birds, safe only in our nests.'

In fact, it is the central character's comeuppance that is the most disturbing feature of the serial. In her case, she blames her imagined offence for her punishment.

The serials define what can and cannot have a presence in the public domain. In other words they present the limits of expressibility in Pakistani society, especially in relation to the male-female relationship.

The dramas present a particular discourse of femininity where a woman has to be docile and obedient. Male authority has to be accepted.

Different institutions supporting patriarchal norms like family, religion and feudalism are present in a very definite manner, but the discourse mounting a challenge to this authority is muted and threatened with punishment. It is made to look bizarre and troublesome.

It causes an inconvenience to the order and stability imposed by the triad of patriarchal-feudal-religious discourse.

In this set-up, a serial like Piya Re -- which also shows male feminists -- comes as a breath of fresh air.

Regressive though the discourse may be in most serials, the quality of acting, the dialogue delivery of the actors and movement of story in time exercises an anesthetic grip on the audience's interest.

Has Pakistan's soft power entered Indian households unnoticed?

Mohammad Asim Siddiqui teaches English at Aligarh Muslim University.