Amit Mistry was a wicked actor, someone who could chance a broken arm, who could take deep dives, who could ram his head into walls, all without bothering about the outcome.

And, as with that closing bit, we would never know where he might have arrived at eventually, notes Sreehari Nair, paying tribute to an unusual performer who passed into the ages on April 23.

Judging by the media coverage it generated, Amit Mistry's death on April 23 was a rather colourless affair.

No long obituaries were published, no articles with titles like 10 definitive films of Amit Mistry, no academic pieces dissecting his craft.

Alive on the 22nd of April, gone the next day, was how most of us in this profession took to the news.

The stoicism, I have to confess, wasn't entirely unearned.

After all, even those who were bowled over by his turn as Moneylender Kuber, in Raj and DK's 99, would be correct in pointing out that that act of controlled mania was now more than a decade in the past.

Serious film journalists, who are frequently required to double as professional mourners, were confronted with the problem of how to eulogise a genuine talent with an almost non-existent legacy. Cannot be accomplished.

And yet, there are times when a solitary performance can become the lens for inquiring into an acting life cut tragically short; for a glorious one-off provides the inquisitor with a chance to silently underscore the parts that were never adequate, the potential that was never fulfilled, the career that never was.

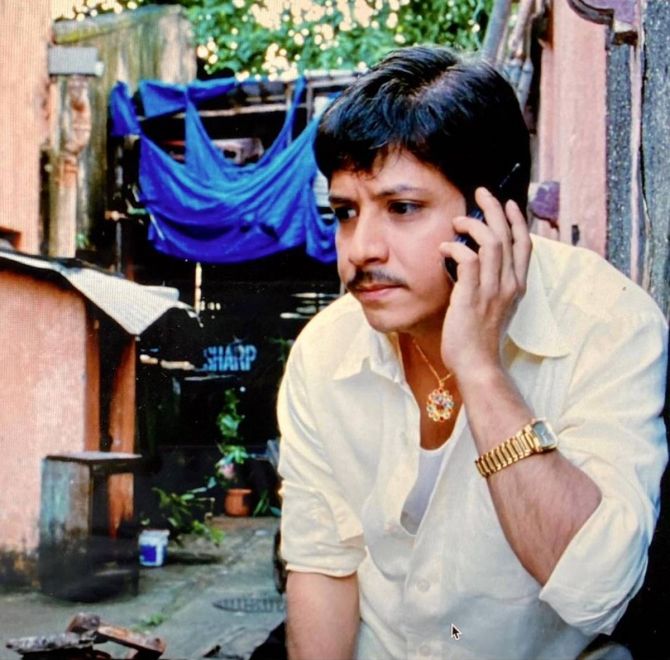

In 99, Amit Mistry appears as a small cog in a large racket, very much a subsidiary character, but one that he, with clear-sightedness and without pounding away for a second, proceeds to make vivid in human terms.

The performance is a handbook for how to craft something mythical out of discrete, spaced-out bits.

I watched it again recently, and this time, I kept count.

Six-and-a-half scenes are all it takes for Mistry to create Bhuval Ram Kuber: A weasel, a rioting lowlife, with a preternatural gift for dramatising his every action, the Duke of Delhi's lanes and gullies, who thinks on his feet, who stays on his toes, he's a poet who doesn't know it, a politician who hasn't made it, and above all, a one-man theatre company.

In a scene of his answering Simone Singh's call, she coos to him lovingly, unaware that it's Kuber on the line, and his facial muscles tighten, his eyeballs slide, his nose puckers into a cross between curiosity and a passing orgasm.

The lady's voice continues unabashed even as the innocent hero searches for a suitable response, gloating, fumbling, blundering along -- and for once, you don't hear a peep from him.

In a film that prides itself on photographing major plot shifts using clever diversions, Amit Mistry's expressions, which switch on a dime, are as much a technical triumph as they are deeply felt.

A scowl, a raised eyebrow, a formal shake of the head, the managerial face displaced by a bout of sudden modesty: It's a private madness that Mistry taps through and through! And because the man was also a brilliant technician, he doesn't project to the gallery, and, instead, allows the camera to pick up flashes of his madness.

Ergo, never once does he come across as heavy-spirited or knowingly crazy.

He gets to utter punchlines, sure, but they feel like compromises for seven expressions that couldn't be thought up on the fly.

In the hands of a lesser actor, the emissions of broken English would have played out like a shtick.

Here, we don't laugh with a liberal's superiority complex but laugh we do at the self-seriousness of the character's pursuit.

In the final episode involving him, he limps away from the scene, but Bhuval Ram Kuber, by then, is firmly embossed in our minds as an insignia of grace mysteriously received.

Amit Mistry's critical reputation, not surprisingly perhaps, mirrors the reputation of the work that contains his finest hour.

99 is a consistently inventive film (Think Kaminey, but without the self-conscious quirkiness) that has exerted no influence whatsoever on the Hindi movies that came after it (In point of fact, nothing that Raj and DK have made since has had quite the same shiv).

Yes, those on-the-nose cricketing metaphors do grate on your ears.

Yes, Cyrus Broacha had too much fun on the sets to improvise in character.

But the actors, overall, do such a terrific job of flitting in and out of each other's spaces that they end up enlarging the scope of the narrative: A tale of betting and match-fixing soon turns into a clash of the underbellies.

This is a film about some bloke in a shady-looking Mumbai office pulling a boner, and some little kid in a Delhi slum profiting from it.

Camping at the intersection of the many underbellies that make up its architecture is 99's true protagonist, Rahul Vidyarthi (He's the punter pitched here as a social equaliser).

Boman Irani, who was the spirit of the 2000s (the 2000s of blog sites, and moral advertising, and chotta recharge), before his brassy acting style got supplanted by the whispery style of Nawazuddin and Irrfan, gives his smoothest performance as a man who prefers to live on the edge of a heart attack.

Without the usual prosthetics, without an attention-seeking accent, without even an erect spine or a confident shoulder, Irani builds Rahul Vidyarthi: A compulsive gambler for whom life is one big shell game.

The film's greatest achievement is that it offers us a peek into the heady sensations that drive a gambler, makes us share in his highs and lows, but does not stoop so low as to lecture us about the evils of his obsession.

Boman Irani goes one step further; he imbues his whole act with the disposition of a dealer and treats those around him as players seated across from him.

Irani, very slowly, sweetens the pot, and forces his co-actors to draw their best cards.

Kunal Kemmu still runs everything past his boyishness (I don't mean this as an insult; on the contrary, it is part of his charm as an actor).

But in his scenes with Rahul Vidyarthi, Kemmu -- faced with the prospect of having to hustle with a person more wised-up than his character -- seems to magically grow up.

As Sachin, he performs some wonderful routines of everyman irritation, and Boman Irani magnanimously vacates the stage, or sometimes, retreats to a corner, where he sits counting currency notes at the speed of thought.

With Mahesh Manjrekar (who has never been funnier), Irani enters into a waiting contest, festooned with faux philosophies and the credo of 'Let us see who blinks first'.

I cannot think of a movie that has better used Vinod Khanna's physical frame and his voice. Raj and DK have carved Khanna's JC very much out of the actor's natural constitution and they take special care to ensure that the character is not embellished out of proportion.

JC and Rahul Vidyarthi are engaged in a war that extends beyond the betting table; it's a class war, and JC's hatred for his rival stems most of all from the smoothness with which Vidyarthi trumps him.

Simone Singh appears as Jahnavi, Rahul Vidyarthi's love interest, and their section features one of the most ambitious romances ever conceived in Hindi cinema.

Bear in mind, we are talking 2009, and to have back then a middle-aged couple indulge in a ping-pong of mistimed confessions, small idiocies, and instant opening of wounds acquired over years of togetherness, was nothing short of courageous.

Plus, to top it all, the whole section unfurls like a behavioural comedy, with none of the simple-mindedness one associates with love.

The beauty of the Jahnavi-Vidyarthi love story is in the pauses and the improvised exasperations; it's in the willingness to let love constantly run into breathers, into its well-deserved dead ends.

Boman Irani, who has won most of his awards for playing comic prigs, in 99 , lords over his school of actors like an all-knowing but generous dean.

And yet, there's one performer who the dean cannot seem to control, who's too imaginative to observe rules.

So what does Irani do? He holds himself back and lets Amit Mistry win out.

Every single time!

In a film filled with misdirections, in which Sudhesh Berry's cop character goes out of his way to give an informer a valuable tip-off, it's only Bhuval Ram Kuber who belts his numbers straight; he's the transparent crook in the mix.

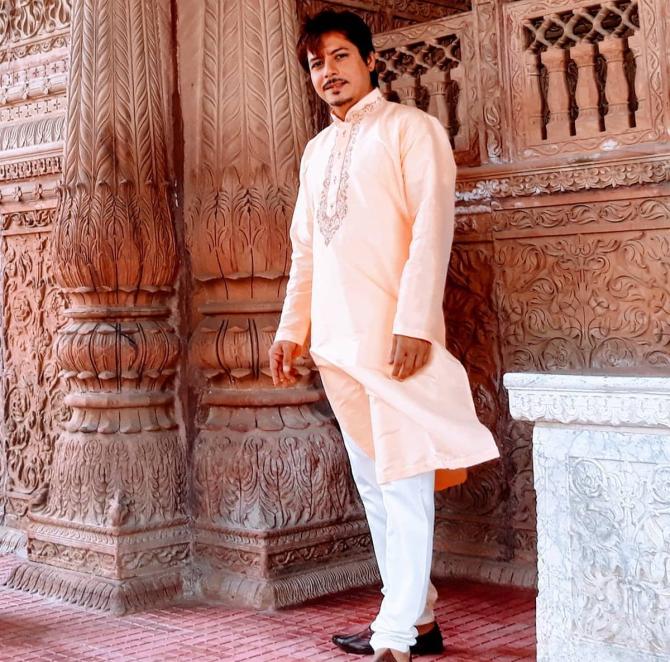

Mistry's personality, in truth, lacked definition. His entire appearance was so weak and blurry that you fear at first that he might go unnoticed.

Just the same, few Hindi film actors have made hysteria look so organic on-screen.

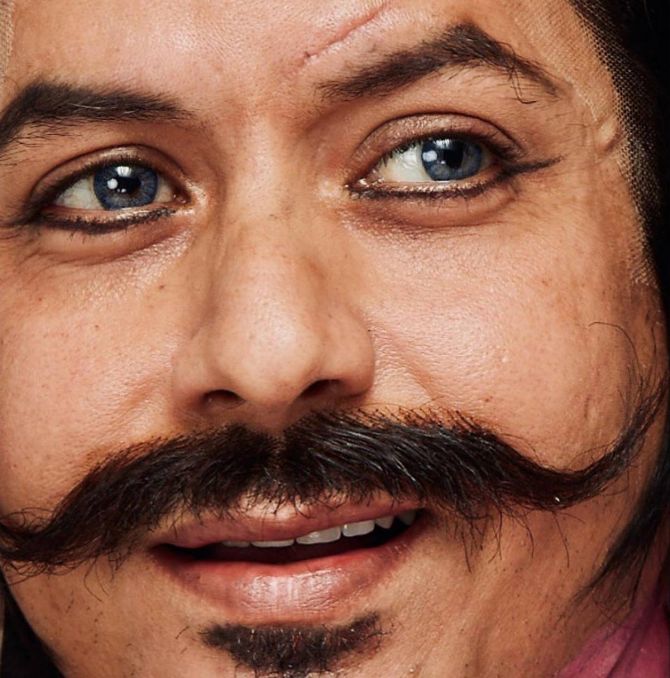

What's remarkable about Amit Mistry's performance as Kuber is that his excesses don't land like excesses.

You don't question his fits of anger, or, the exaggerated movements of his hands, which transform him from a concerto maestro one moment to a frisker in a shopping mall the next, with quick attempts now and again at impersonating an umpire signalling a free-hit.

We stay so tight with the self-memorialising prick that in his final scene, where he gets shot in the hand, then slumps into a car wailing, before driving off and plunging the vehicle into a barrier well beyond our field of vision, we may be left straining our neck.

Caring about the funnyman, wondering about his fate, is not done; that doesn't happen every day.

Kuber's last waltz is also the perfect idiom for Amit Mistry's approach to his craft.

He was a wicked actor, someone who could chance a broken arm, who could take deep dives, who could ram his head into walls, all without bothering about the outcome.

And, as with that closing bit, we would never know where he might have arrived at eventually.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com