'Hrishi-da often voiced his disenchantment with Bachchan's Angry Young Man persona -- the 'maara-maari', the growth of sidelocks; he even said directors were killing Amitabh the actor and turning him into a stuntman. Yet, as Jaya Bhaduri jovially pointed out, the seeds of that seething persona can be found in Anand and Namak Haraam.'

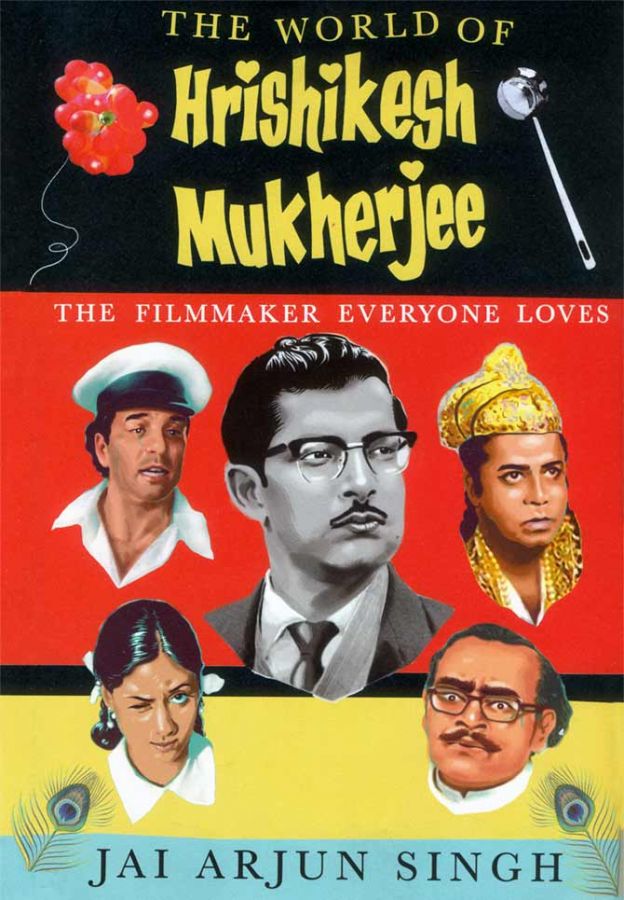

A fascinating glimpse of the Amitabh Bachchan-Hrishikesh Mukherjee magic, from Jai Arjun Singh's The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

In a special 2010 episode of the game show Kaun Banega Crorepati, hosted by Amitabh Bachchan, the appearance of Dharmendra as a guest allowed audiences the nostalgic pleasure of watching Veeru and Jai (or Professor Parimal and Professor Sukumar) bantering and reminiscing, thirty-five years after their most memorable work together. And Dharmendra reversed the show's usual order of things by asking the first question:

"Amit, hamaaray kaun se aise director thay jin se hum dono ghabra jaate thay, darte thay -- jaise kisi schoolmaster ya headmaster se? (Amit, who was the director we both were afraid of, the same way we'd be afraid of a schoolteacher or principal?)"

If the question had been addressed to a regular KBC participant who judged the personalities of directors by the things that happened in their movies, he would have needed a lifeline or three to get the answer right, and may have faced eviction nonetheless.

Ramesh Sippy, he might have said first, thinking of Gabbar's sadistic games or Shakaal and his torture chamber (Shaan) or Seeta being tormented by her vicious aunt (Seeta aur Geeta).

The second choice may have been Manmohan Desai, who planted Dharmendra in a miniskirt and Amitabh in an Easter egg in separate film released in the same year. But no.

"Hrishi-da ke saath hum dono kaampte thay kyuki unka ek rutba hee aisa tha (We could tremble before Hrishi-da, such was his aura)," Bachchan told the audience.

***

From the beginning to the end of his career, Hrishi-da cast popular actors in lead roles. The list includes those who had an established screen persona before they worked with him (the 1950s star triumvirate of Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand falls in this category, as do Meena Kumari, Suchitra Sen, Guru Dutt and Mala Sinha), it has younger performers whose screen images were to some degree or other shaped by him even though some of them went on to do other kinds of roles (prominent in this list are Dharmendra, Jaya Bhaduri, Rajesh Khanna, Amitabh Bachchan and Rekha), and it includes actors who tended to be more malleable, less associated with a specific type of role: Balraj Sahni in Anuradha, Usha Kiran in Musafir, Ashok Kumar in Aashirwad, Sanjeev Kumar in Arjun Pandit.

The big stars of the 1950s brought the baggage of their existing images to the early films, with variable results. So Dilip Kumar fits very well in Musafir because it is a Devdas-like role, exactly what the third segment of that film calls for. Raj Kapoor is mostly well used in Anari, and the film has other good things in it in case you get tired of him, including fine performances by Lalita Pawar, Nutan and Motilal; on the other hand, the self-flagellating aspects of Kapoor's screen persona are allowed to go badly out of control in the 1962 Aashiq, which is one of Hrishi-da's most pedestrian films.

However, to watch Rajesh Khanna and Amitabh Bachchan in Anand, Dharmendra in Anupama, Jaya Bhaduri in Guddi or Rekha in Alaap or Khubsoorat is to see the creation of fresh possibilities, and a more assured helmsman, moulding fresh clay to his requirements.

Working with these younger actors before they had become too set in their ways, Hrishi-da could use them in specific types of roles, toy with our expectations of them: Consolidating Dharmendra's bhadralok persona and later using him so well as a comedian; or allowing Bachchan's flair for simmering anger full expression in a framework outside of mainstream cinema.

Even in the early days, he had a clear knack for seeing how a new actor would fit into the desired universe of a film. He chose the fresh, arch Leela Naidu for the title role in Anuradha himself, and watching the film you can see how she brings an immediate plausibility to so many scenes, such as the one where Deepak (after realising that Anuradha is in love with someone else) tries to be the noble, martyred man, offering to shield her from her father's wrath by claiming that he doesn't want to get married -- to take the responsibility on himself -- but Anu refuses to be the submissive, favour-accepting woman; she holds her head high and says no, this is my cross to bear.

Not that Hrishi-da always had his way even with the younger lot. 'Don't mind your make-up -- make up your mind,' Sharmila Tagore recalls him saying aphoristically during the shooting of Anupama, and apparently there was good reason for this. Here was a film about a diffident wallflower who had grown up without parental love, didn't have any friends and stayed cloistered in her large, cold house; and yet Tagore, who was just rising to stardom and on the rush of being a Hindi-movie heroine, insisted that she wear her stylish bouffant hairdo in the film.

'Hrishi-da tried telling me the hairstyle simply wasn't right for the character, that it was too trendy,' she told me during an interview, 'but I was immature and persistent and wouldn't listen -- and so eventually he gave in and said we'll work something out. He managed to shoot me in such a way that the character didn't look unduly glamorous or dolled up, but it was a small blot on the film's integrity, and I still feel guilty about that.'

***

Still, counter-intuitive casting is another of the small transgressions one sees in Hrishikesh Mukherjee films. Rajesh Khanna, one of Hindi cinema's biggest romantic superstars, rarely had a love interest in the movies he did with Hrishi-da. Anand, Bawarchi and, to an extent, Namak Haraam were all built on the idea of Khanna the superstar as inspiration/mentor/panacea for all ills, and his only onscreen romance in any of these films is with Rekha in Namak Haraam; even there his character Somu has a far more intense relationship with his friend Vicky (Bachchan).

(It is one of those little quirks of Hindi film history that the first time Rekha and Amitabh Bachchan -- soon to be such a celebrated onscreen couple -- appeared in the same film, not only did their characters have no scenes together, they were also in love with the same man!)

In her book Amitabh: The Making of a Superstar, Susmita Dasgupta notes that Hrishi-da 'was one director who, in the course of his eight films with the star, actually exhausted the full pantheon of Amitabh's histrionic abilities'. And while it's tempting to think of the films Bachchan did with Hrishi-da as lying outside the mainstream of his career, there are clear links between these roles and the ones he did in blockbusters for Manmohan Desai and Prakash Mehra -- links that are also revealing of the differences between the 'commercial' and the 'middle'.

***

Hrishi-da often voiced his disenchantment with Bachchan's Angry Young Man persona -- the 'maara-maari', the growth of sidelocks; he even said directors were killing Amitabh the actor and turning him into a stuntman. Yet, as Jaya Bhaduri jovially pointed out, the seeds of that seething persona can be found in Anand and Namak Haraam (the latter released around the same time as Zanjeer, which is usually reckoned the beginning of the Angry Young Man era).

At the same time, Hrishi-da knew how to tap the actor's comic flair: the scene where Bachchan launches into a description of a 'corolla' in Chupke Chupke is a pre-echo of the high-sounding gibberish in 'My name is Anthony Gonsalves' (Amar Akbar Anthony); and the drunken scene in Namak Haraam is a precursor of more famous drunk scenes to come in movies like Naseeb.

In later years, even Hrishi-da couldn't fully escape the trappings of the Bachchan persona. The inclusion of a (half-hearted) dhishum-dhishum scene with the actor in Jurmana was a sop for the audience.

'When I showed Amitabh slapping an eve-teaser in Bemisal,' he said once, 'someone in the audience grumbled, "What's wrong with this director, he can't even show Amitabh getting angry properly."

For a sense of the difference between the Bachchan persona as it was used in the mainstream and in Hrishi-da's work, try a little comparison of Bemisal with Prakash Mehta's 1978 film Muqaddar ka Sikandar.

Such comparisons can naturally never be exact, but there are similarities between the films (just as there are similarities between the characters Bachchan plays in Hrishi-da's Mili and Yash Chopra's Kaala Patthar -- two men haunted by the past, even though one shuts himself up in a terrace flat in a building populated by middle-class folk while the other ends up in a coal mine, courting death every day).

Both Bemisal and Muqaddar ka Sikandar involve an uncomfortable sort-of-romantic-triangle, with the hero in love with Raakhee but arranging things so that she ends up with the 'right' man for her, his close friend (Vinod Mehra in Hrishi-da's film; another, more glamorous Vinod Khanna in Muqaddar ka Sikandar).

In both, we see the younger version of the Bachchan character (played, inevitably, by the droopy-eyed Master Mayur) and understand how the child is father to the man -- we learn of this man's sense of indebtedness, his deep gratitude for the emotional or physical support he has been given, and how this informs his future actions.

In the style of the mainstream melodrama, Mehta's film clearly spells out Sikandar's dilemmas and impulses, leaving almost nothing out of sight, and ending with the catharsis-providing death scene that was central to many of Bachchan's roles. We are expressly asked to view him as the self-sacrificing hero, the Sikandar who conquers his own demons and his own ill-starred fate before conquering the hearts of everyone he comes in contact with.

Bemisal is a very different matter. Even at the end of that film, the Sudhir character remains an enigma. He emerges after spending a few years in jail, to a tearful reunion with his old friends and their little son, but this is hardly closure in the sense that the death scene in Muqaddar ka Sikandar is: The viewer knows that not only can Sudhir never practise as a doctor again, he will probably be dependent to a large extent on his friends, including the woman whom he was once in love with and who now has a family of her own.

And this may help explain why those who have followed Bachchan's career closely regard Bemisal such a key film. To watch it is to get a glimpse of the little things that may have been lost to us as his career followed the arc it did.

How fortunate it is that even at the peak of his stardom, he couldn't say no to Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

Excerpted from The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, by Jai Arjun Singh, Penguin Viking, 2015, Rs 599, with the publisher's kind permission. You can buy a copy of the book here.

Excerpted from The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, by Jai Arjun Singh, Penguin Viking, 2015, Rs 599, with the publisher's kind permission. You can buy a copy of the book here.