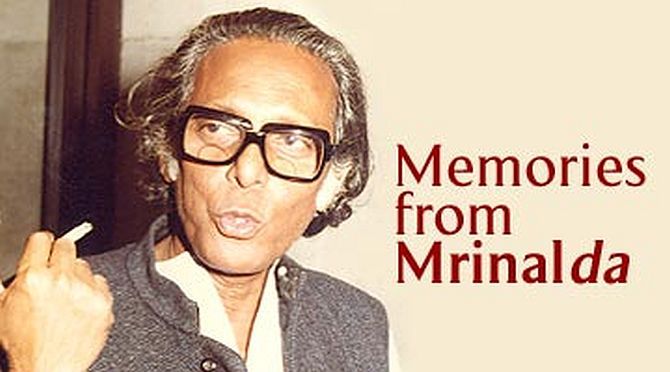

Mrinal Sen, one of India's greatest film directors, passed into the ages on December 30.

In this excerpt from a conversation with Samik Bandopadhyay, Mrinalda discusses three legendary actors he has worked with.

Smita (Patil) knew she wanted to do the role.

And Shabana (Azmi) knew she wanted to, too.

They knew that I was working on this film.

They were then acting in Mandi. Shabana was the landlady.

Smita was the prostitute.

And Sreela (Majumdar) was in it too.

Both of them called me up and said that they wanted to act in my new film.

And Sreela too, following their example, pitched in with her request.

I told her to calm down.

'You are practically family.

Stop worrying.' I sat down and wrote to both Shabana and Smita.

'You are definitely acting in my next film. But unlike Shyam (Benegal), I cannot move about with a harem, like a Mughal emperor. He can take plenty of women at a time, but I can't take more than one woman at a time.'

'I start with you. After you, I'll take on another actress. You are a great actress. So is the other one.'

I wrote 'Dear Shabana' on one and 'Dear Smita' on the other.

I deliberately interchanged the envelopes and sent them off.

I got to hear of the end result much later, from Shyam (Benegal).

They were at the dinner table.

It was during the filming of Aarohan (produced by the West Bengal Film Development Corporation).

They had exposed 10,000 feet in order to shoot some lightning. I was told by the best laboratory of West Europe that they had never seen lightning shot this way before. I borrowed some of that forGenesis.)

Shabana came to dinner, wearing a long face. And told Smita, 'This is a letter for you.'

And Smita too, pulling out a letter from her wallet, said, 'Here, this one's yours.'

(Laughs.)

They confessed that they'd had a big laugh about it.

Shabana could really put one on the spot.

One couldn't say no.

One never had a chance to do so.

I was visiting Shabana once at her father's place in Juhu.

As I got up to leave, she gave me a rose.

We exchanged kisses and left.

This was before Khandahar (1983).

The moment I stepped out, I met Smita who had come to collect her parents.

They were on the way to Prithvi Theatre to watch a play.

There I was, outside Shabana's house, clutching a rose to my breast.

Like a Mughal emperor on his way to war! 'Mrinalda, I've caught you at it!' she exclaimed and hugged me.

I didn't know what to say.

'I'm sorry. Do forgive me.'

'No. I've caught you this time. There is only one way you can atone for your sins. You must watch my film Umbartha tomorrow.'

'But my plane leaves at noon tomorrow.'

She was not to be swayed and fixed it up so that I could watch it at the laboratory itself.

Somewhere near the Film City. It took an age to get hold of a print and by the time we began watching it, it was almost ten thirty.

The film was a long one, and Smita's parents were there too.

I sent off a young man who was with me, to the airport, to check in.

The moment the film ended, I ran to the car.

'I cannot speak with you now. I must be off or else I'll miss my flight. Well done.'

I patted her on the back and was off.

'Next time I come I'll have puran polis with you,' I told her parents, her mother in particular.

She used to make them for me especially and send them over.

Smita's mother used to tell me about how she had spent a lot of time traveling with her husband, on political work for the Congress.

She said to me, 'I would like to be with your team when you work. I can cook. I have heard so much from Smita. All of you become like one big family. I would like to be a part of it.'

I promised Smita that I would call her when I reached home.

But she called me first.

'How did you like it?'

'I thought you did very well, although I have my reservations about the film as a whole,' I said.

'I forgive you then, since you did make time to watch the film,' she replied.

After that, when I completed Khandahar, I received a long fax from Cannes.

My faxes would come to the Grand Hotel, in those days.

They had written that although they had seen Khandahar, they could not accept two films from the same country.

They had heard of Ray's Ghare Bairey<./p>

And we convinced that this was his last film because he had fallen sick while filming.

They had started this festival with Pather Panchali.

Let the Cannes festival end with Ghare Bairey, they requested.

No one had seen his film yet.

And everyone was worried -- if my film won an award and his didn't, then that itself would perhaps kill him off.

They said they would extend every support to me and my film, but that I must concede to this one request.

They screened it, but out of the competitive section.

I had nothing to say.

The people at Venice were enraged.

'Why didn't you give it to us?' Anyway, then it went to Montreal. Where it got the Second Prize.

And to Chicago where it got the Best Film Award.

Then, it was also included in the Film Guide -- where the five best films from all over the world are chosen every year.

Gilles Jacob, director of the Cannes Festival, was present at the Montreal Festival.

It is a French-speaking region and Smita was part of the jury too.

Gilles called me up one morning: 'Mrinal, though I am leaving this morning, and a friend of mine from India is also leaving, can we meet over breakfast? We perhaps have no time for lunch.'

I agreed.

I also knew that the friend she wanted to bring for lunch would be none other than Smita.

She congratulated me warmly, and said, 'Mrinalda, I simply have to tell you this. I have never seen Shabana look so beautiful before.'

It was such a compliment and such an honest confession.

Although there were undercurrents of tension between those two leading ladies.

Just before that, referring to Smita, Shabana had told me, 'Mrinalda, this woman is sick in the head.'

That was the difference between the two. Geeta was very fond of Smita.

Gilles Jacob said, 'You've taken her for one film which won an award at Berlin. I want you to make another film with her, which you must give to me. To my festival.'

I agreed.

Smita quickly picked up a paper napkin and wrote down this decision.

And I signed it, putting down the place and the date.

Gilles signed it too and so did Smita.

And I remember absolutely clearly, how lovingly and gently she folded it and put it away in her handbag.

Three months later she was dead.

I was getting hourly updates on her condition.

The moment I heard about her death, I sent off a fax to Jacob.

And he called me back immediately.

'Whom can I call up, to pay my condolences?'

I gave him Smita's husband's number. It was very sad.

One of the city's most famous doctors had confided to me -- a gynaecologist -- 'One of us is responsible for her death. I visit Bombay frequently and have heard about it. She died because of gross negligence.'

* * *

One morning I visited Khwaja Ahmed Abbas (1914 to 1987, journalist, columnist, scriptwriter and film-maker), who lived next door.

'Abbas-saheb,' I said. 'I'm making a film.' 'Yes, I've heard.'

'And everyone in it is new. If I go to the Films Division, I know I will get plenty of people -- Pratap Shama and the like -- whose voices I can use. But I don't want to. We are all such old friends. I want a new voice. Since everyone else is new, I would like this person to be an unknown figure too.'

There was a young man there, amongst many others.

Tall. Thin. 'Mrinalda, aami Bangla jaani. Aami kolkatay chhilo,' he said. (Mrinalda, I can speak Bengali. I used to live in Calcutta.)

I told him, 'Your Bengali is lousy, but your voice is great. And for your information, my film is a Hindi one.'

'The name is Bengali and the protagonist is also Bengali, but it's a Hindi film.'

'I need your voice for a few words a little after the movie begins and then a little bit again, towards the end.'

'Are you willing?' I had to trade with his director.

This young man was working in a movie called Saat Hindustani, at that point.

His director, Abbas, said the chap was being loaned to me on condition -- that I would get him Utpal in return.

I agreed.

I took the young man to Jagdish Banerjee's house -- he had done some work for the Films Division -- who agreed to do the recording.

We had a budget of only one-and-a-half lakhs and so had to skimp at every turn.

Oh, what a trial that was.

The sound of fish being fried next door and then the smell of that same fish wafting past us.

It was impossible.

I said, 'What the hell! Let's spend some money anyway.' So off we went to Blaze, where we finished the recording in twenty minutes.

There was a Hindi translation of Sonaar Bangla.

The young man asked me, 'Mrinalda, shall I say "Sonaar Bangla"?' I agreed.

When I went to pay him, he refused.

'This is my very first work in films. I simply cannot accept money for it.'

I reasoned with him.

'Look, all of us are accepting payment. You cannot insult us like this. Take it professionally. Is this your profession?'

'Yes,' he replied.

'Well then, make a start with this.'

So those three hundred rupees were his first earning in the world of films.

When I asked him for his name, for the credit line, he simply said, 'Amitabh.'

At that point he was still undecided about whether he would keep the Bachchan part of it.

Amitabh Bachchan had spoken the commentary for Bhuvan Shome.

Excerpted from Mrinal Sen: Over The Years, An Interview With Samik Bandopadhyay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

This feature was first published on Rediff.com on February 1, 2005, the day before he received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award for his many sterling contributions to Indian cinema.