'The Maharashtra government's diktat is another meddling example in an industry where politics or language has no role to play.'

'Cinema has a universal language. Filmmakers are divided across regions, but united in their passion for films,' says director Suparn Verma.

In 2000, when Atal Bihari Vajpayee was prime minister, his government conferred the title of 'industry' on the filmmaking business.

In 2001, a tax holiday was announced for converting single screen real estate hoarding theatres into multiplexes. This was extended again in 2011.

Since then, the government has been taxing the industry at bizarre levels.

In Maharashtra, for example, this is the tax system -- entertainment tax is levied at 45 per cent for tickets under Rs 250, at 49.5 per cent for tickets priced between Rs 251 and Rs 350, at 51.75 per cent for tickets costing between Rs 351 and Rs 500 and at 54 per cent for anything beyond that.

The service tax stands at 14 per cent. Besides, the industry pays a five per cent value added tax on non-theatrical rights and a stamp duty on all contracts in Maharashtra.

To foster regional Marathi cinema, the government earlier made the films tax-free. Then, in return for the tax holidays given to multiplexes, the state government made it mandatory for all multiplexes to reserve one show a day for local language films.

The multiplexes started showing these films at matinee shows.

Over the last few years, some great Marathi films have been produced with regularity and have gone on to win international and national awards.

At the box office, they never found the adequate number of screens that would give them the chance of a good run. Films like Riteish Deshmukh's breakout hit, Lal Bhaari, or Duniyadari were exceptions as they were backed by heavyweight actors or producers.

On April 7, Maharashtra's Culture Minister Vinod Tawde issued a diktat that one screen at all multiplexes in the state should screen a Marathi film during the prime time slots of 6 pm or 9 pm.

Some have welcomed the move; others have protested against the government's attempt to order how businesses should run.

A few things need to be put into perspective with regard to the business of films and the ground reality behind the numbers you see screaming at you in paid news or advertisements.

The film industry has grown in size and business.

As per ASSOCHAM, Indian film industry revenues are expected to grow by 56 per cent to Rs 12,800 crore (Rs 128 billion) this year from Rs 8,190 crore (Rs 81 billion) in 2014 due to increasing digitalisation of the sector.

Over 60 per cent of this revenue comes from Hindi films.

The Bombay (film distribution still works as per the old British map so Bombay city, Goa, Gujarat and parts of Maharashtra and Karnataka that belonged to the old Bombay Presidency) territory accounts for over 60 per cent of a film's box office collections.

The new rule imposed by Minister Tawde and his government will hurt.

The industry is in a wait-and-watch mode to gauge the actual monetary impact. Some have been vocal about the government's attempt to save regional cinema in a free trade world. Some have suggested that setting up low cost theatres would be a better option.

Currently, Marathi films have only two big centres, Bombay and Pune. The Konkan region barely has any multiplexes. Neither do Satara, Kolhapur, Nasik or Sangli.

My contention is that the way things stand today, Hindi films and all regional cinema are in the same leaky boat except for the South film industry which has insulated itself from the impending catastrophe.

Let us look at the fundamentals that are against the entire business of cinema, with the above-mentioned southern exception.

The multiplex exhibitor cartel

In 1999, the Hindi film industry went on strike because the multiplex bosses had joined forces and, after taxes, the producer's share in the first week -- which garners the most income -- was a meagre 30%.

After many weeks of negotiations -- with Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan stepping into the negotiating ring -- a new figure was reached. Some say the release of the film 99, which broke the strike, caused the film industry to wrap up negotiations without the desired result.

The new sharing rate since is 48 per cent in the first week, 42 per cent in the second week, 32 per cent in the third, and so on. Though Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Yash Raj Films still try and renegotiate rates when they have a big film coming out, this is the industry standard.

The multiplexes have dynamic pricing as well as dynamic screen timings. Depending on the success of a film, they keep changing the programming unless given the rental by the distributor or producer.

Regional and independent Hindi films have it worse, with producers scrounging to find screens to show their films.

Multiplexes have become so cut-throat that they now charge producers for trailers. At times, they even remove trailers attached to a certain film as an understanding between the makers.

They make additional amounts by playing advertisements lasting 20 minutes before and during the interval of the film. Plus they sell snacks at highly marked up prices, something we are all familiar with.

This money is not seen by the film producer.

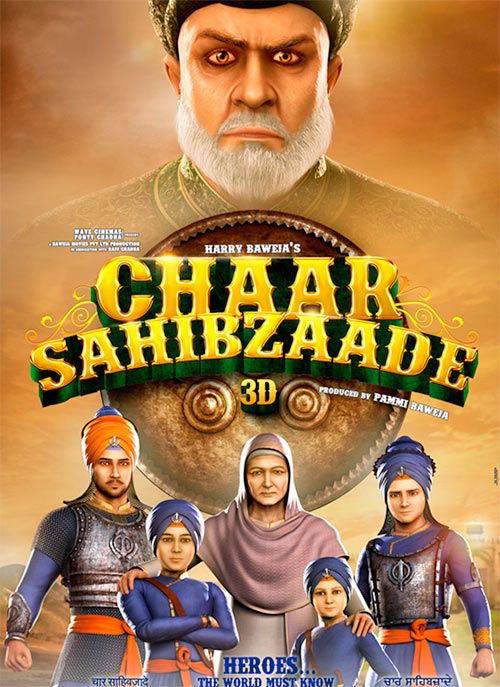

One of the biggest hits last year was Harry Baweja's animation film in Punjabi, Chaar Sahibzaade. It is also a story how the system let down this filmmaker.

Harry first ran pillar to post to get a decent release in Punjab as that was his principal market. He mostly got matinee shows.

The film received great word-of-mouth publicity and picked up in the second week, running to houseful shows. This week on, he got all four shows on all days in all the movie theatres.

But, behind his triumphant smile, lies the tragedy.

With each passing week, where his film was screened in theatres that were houseful, his share kept going down.

He gambled everything he had on this film, yet he stands to make the least amount of money because of the way the share system works.

Satellite Television Market

At one time, the producer could recover up to 75 per cent of the film's budget by selling satellite television rights alone.

Three years ago, barring a rare exception, television channels stopped buying the rights of Marathi films. Since last year, the prices of Hindi films have bottomed out as well.

Ek Villain, one of the biggest musical hits of last year, was sold for a ridiculously low price. A few years ago, it would have fetched anywhere between Rs 12 crores and Rs 17 crores (Rs 120 million and Rs 170 million).

Music

The once-booming market died out with the advent of MP3s and piracy.

The whole model changed.

Today, deals are done against offsetting publicity costs in most cases. Which is the reason Yash Raj Films has its own music label to exploit its content.

Piracy

VCDs and DVDs are sold openly outside movie theatres the very day a film releases. Movie ticket prices are partly the reason why this happens.

A family comprising four or five members cannot afford to watch more than one movie in a theatre. They prefer a Rs 50 VCD over a Rs 100 DVD.

Considering this disparity, it would be interesting to see how many families actually turn up at multiplexes showing Marathi films with ticket prices that aren't the usual subsidised rates.

Politics

If Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis was really interested in promoting films, he would have ordered multiplexes to screen regional cinema and independent films of every language in the prime time slots.

But this is more a case of manipulating the sentiments of the Marathi manoos to counter the Shiv Sena and the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena.

Till last year, film trade unions supported by the Shiv Sena, the MNS and the Nationalist Congress Party ruled the roost. Now, the BJP has formed its own trade union wing, spearheaded by Mumbai designer Shania NC, called the BJP Chitrapat Union.

Politicians use the star appeal of actors for election campaigns and causes, but have done nothing for the film industry.

Print and Advertising

P&A is a monster that is now out of control.

The reason the South industry has managed to curb it is because the producers got together and made a rule that, be it a big budget film starring a mega star or a small budget film starring newcomers, no film's P&A can exceed a certain budget.

Sadly, this is not true of cinema in any other language. Today, you can pull in favours and make a film in a budget of Rs 1 crore (Rs 10 million), but the minimum budget required for publicity to be visible is Rs 6 crores to Rs 7 crores (Rs 60 million to Rs 70 million).

A few weeks ago, some top filmmakers met and agreed to limit publicity costs. The very next day, an upcoming mega budget film released a full page campaign.

Earlier this week, Fox Studio released a front page ad showcasing its upcoming films.

To make things worse, there is Hollywood.

Hollywood

Fast and Furious 7 released last week and broke every record over the weekend in India. It even pushed a high profile YRF release into a corner.

Its print and publicity budget was Rs 14 crores (Rs 140 million) and the film released in over 2,000 screens. FF7 has already made Rs 48 crores (Rs 480 million) over the weekend.

Avengers 2 is due to release in a couple of weeks and it too has a big P&A budget.

From trying to compete with Hollywood's production values, the Indian film industry now has to complete with the P&A budgets of studios with deep pockets.

To make matters worse, all Hollywood films are dubbed in every possible regional language -- from Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Gujarati down to Bhojpuri!

If a rule had to be passed to protect the Indian film industry, it should be that Hollywood films cannot be dubbed in regional languages to protect the local industry.

We just have to look back in time and see how Hollywood gobbled up the European film industry.

The latest diktat is another meddling example in an industry where politics or language has no role to play.

Cinema has a universal language. Filmmakers are divided across regions, but united in their passion for films.

The Centre and state governments need to wake up before it is too late.

If the language of money is all that the government will listen to, then listen to this: The entertainment industry makes up for 0.5 per cent of the nation's GDP.

Suparn Verma is a well-known filmmaker and a member of the founding editorial team at Rediff.com