'I believe politics was imposed on it by the censor board, when it gave the film's trailer an A certificate, hoping to deny children, teenagers the opportunity to watch it during prime time television shows,' says Aseem Chhabra.

When filmmaker Hansal Mehta and his scriptwriter Apurva Asrani planned to make the film Aligarh, they wanted to emphasise the invasion of privacy and personal space of a quiet, shy man.

And as I wrote about the film after it premiered at the Mumbai Film Festival, Aligarh is a heartfelt narrative of a gay man's (the late Aligarh Muslim University Professor Shrinivas Ramchandra Siras) plea to be left alone.

One can say all art is political, but Aligarh was not necessarily meant to be a political film. I believe politics was imposed on it by the Indian censor board, when it gave the film's trailer an A certificate, hoping to deny children, teenagers the opportunity to watch it during prime time television shows.

Censor board chief Pahlaj Nihalani is on record to say that the trailer was given the A certificate because the topic of homosexuality is not for kids and teenagers to watch. It seems Nihalani has not heard of the Internet and its reach.

While I do not know the demographics of the people who have watched the film's trailer on YouTube, as of last week it has nearly 2.2 million hits. And that is a huge number for what is an art-house indie film.

Nihalani has also said that his intent is not to deny people (he used the word 'sabotage') from watching Aligarh, but by restricting the film's trailer that is exactly what he is doing.

Aligarh opens on February 26 and I wish the film all the luck it needs. It is a must see film for all thinking people and it is bound to lead to important conversations and hopefully change many minds. Aligarh promises hope.

It should be noted that the censor board's homophobic position is not preventing other filmmakers from expressing themselves. While the Supreme Court of India once again deliberates a plea by activists to scrap Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a range of filmmakers, working in different languages are already taking up subjects that have LGBT themes.

They do not need the laws to change to tell their stories. Just like during other historical social and political movements, these Indian filmmakers are in the forefront of the struggle for LGBT rights.

Some of these films are more political, while others are personal stories, but each has a unique perspective of what it means to be gay, lesbian or transgender in today's India. Here is a look at some films that will follow Aligarh.

Daaravtha/Threshold (Marathi)

Daaravtha is one of the most heart-warming films I have seen in recent times. This 30-minutes short by Nishant Roy Bombarde (producer of the National Award-winning Elizabeth Ekadashi and Sairat, which premiered last week at the Berlin Film Festival), tracks a story of a young boy -- Pankaj, also endearingly called Pankya or Panku (Nishant Bhavsar), who is a little bit different from his peers.

Pankya is not interested in sports. He would much rather learn to dance with girls of his age group, get henna designs on his hands, play with his mother's makeup kit. He is also attracted to an older boy Milind, who has just moved to his village. And for all of this, he is often gets bullied by the other boys in his school.

Pankya is cast in a school dance performance, where he will get a chance to play the female love interest to Milind's character. But Pankya's father is shocked and pulls his son out of the dance performance. Only Pankya's mother (played by the lovely Marathi actress Nandita Patkar) understands him.

Through the 30 minutes of this beautiful film, Bombarde and his characters do not address issues of sexuality and gender. The film does not take a political stand on these matters. Instead by focusing on -- at times the sad life, although he does dream of happy moments -- of a young boy, Daaravtha emphasises the need for compassion and how important it is for us to appreciate those who may be different from us.

It is really unfortunate that the censor board has given Daaravtha an A certificate. This film should be seen by all, especially by teenagers, many who grapple with similar issues and have no recourse to understand why they are different from others.

The Space Between (English/Hindi)

A short film directed by Will Sankhla, The Space Between looks at an upper middle class gay couple living together somewhere in India.

Everisto (Sankhla) is suffering from a terminal illness, but he forbids his partner Yojan (Prabhat Raghunandan) to accompany him to the hospital.

How will Everisto explain his relationship with Yojan to the hospital and to his family, he asks.

In a quiet, sparse manner The Space Between raises what could be a pressing issue to many same sex couples in India. How can they give legitimacy to their relationships when the State outlaws their love for each other?

The film clearly indicates that the argument against Section 377 has to go beyond the case of sodomy and such sexual practices. The law, plus the social norms, prevent consenting adults to love each other and publically show what their relationships mean to them.

LOEV (English/Hindi)

The least political of the new crop of films, LOEV plays next month at the SXSW festival in Austin, Texas. The film focuses on the lives of a group of gay men, their love, their heartaches, heartbreaks and everything that come in between relationships.

The three main characters in director Sudhandhu Saria's film are mostly comfortable with their sexuality. They are not seeking any redress or legitimacy from the State. Rather they are grappling with the complexities of love, much like most straight folks do.

Jai (Shiv Pandit) is a successful businessman from New York, who was once married to a woman and has a child from that relationship. On a brief business trip to India, Shiv decides to spend the weekend with his friend Sahil (Dhruv Ganesh). But then Jai and Sahil are definitely more than friends. There is love that they shy away from addressing.

To this, director Saria adds another layer, as Sahil also has a boyfriend Alex (Siddharth Menon), and they bicker, argue and yet care for each other like other couples.

Jai and Sahil will experience caring moments over the weekend in Mahabaleshwar. But their love -- often unspoken and unrequited -- will mostly hurt. Ultimately Jai, Sahil and Alex are seeking happiness. But happiness eludes them.

LOEV is a terribly sad film, although there is a lot of beauty in its sadness.

White Nights (Malayalam)

Director Razi Muhammed, a graduate of the Film and Television Institute of India, takes Fyodor Dostoyevsky's classic story White Nights and gives it a LGBT spin.

Manav (Disney James) is an artist trained from a school in Baroda. He is haunted by a mistake he made in his youth and now lives a quiet, reclusive, life in Kerala, where he paints, and often drives people in the rural countryside.

One night he sees a woman Chelli (Smitha Ambu) on a bridge. Over five nights the two meet at the same spot, narrating their life stories to each other. Manav promises he will not fall in love with Chelli. But such promises are hard to keep.

But their love will never be fully realised, since Chelli has promised herself to a woman Jyothi (Saritha Kukku). And so Chelli waits each night on the bridge for Jyothi's arrival.

The nights are long, and Chelli and Manav's stories are full of pathos. They have made errors in judgement, but now they seek better lives.

White Nights is beautifully shot, exploring Kerala's lush green countryside and other natural beauty. And the film is packed with lovely music and songs -- the lyrical sounds of rural Kerala.

Ka Bodyscapes (Malayalam)

In 2013 New York-based filmmaker Jayen Cherian made a film Papilio Buddha, which dealt with caste, class and sexuality issues.

While the film played at some festivals including in Berlin, his political positions did not go well with the Indian censor board and Papilio Buddha was practically banned in India.

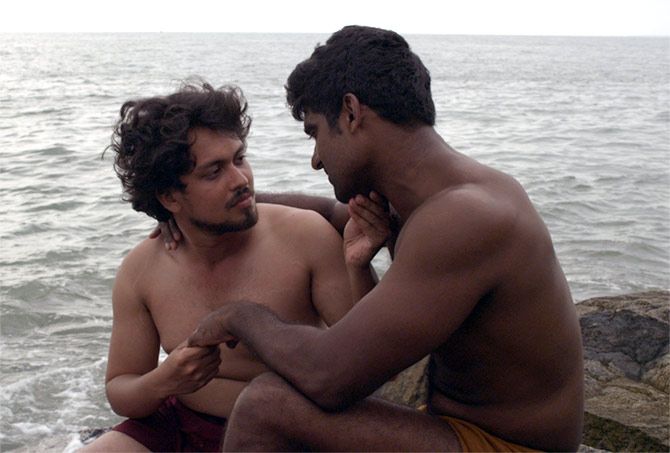

Cherian's new film Ka Bodyscapes is a lot angrier in the way he addresses LGBT issues. On one level the film focuses on the love affair between two young men, Haris (Jason Chacko), a painter, and Vishnu (Rajesh Kannan), a kabaddi player who is now seeking a corporate job.

Their friendship rattles Vishnu's bosses. Meanwhile, a female friend of the two, Sia (Naseera), is focusing on women's rights activism.

The three young characters are set for a confrontation with the authorities and society, as Haris plans a show of his sexually explicit paintings.

A powerful film, with elements of how artists like M F Husain were treated in India, Ka Bodyscape will stun the audiences. The ending will haunt the viewers for long.

It is hard to say how Ka Bodyscapes would work in India, given the current political climate in the country. It is remarkable that a filmmaker like Cherian is able to take chances and make a film without worrying about the reactions to it.

© 2025

© 2025