'It took a 75-year-old director to teach the reformist set of Facebook users that Evil is not an aberration, but something that resides in the most regular seeming of human beings,' says Sreehari Nair.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is blessed with a 'sincere moustache'; the kind, John McPhee had once talked about.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is blessed with a 'sincere moustache'; the kind, John McPhee had once talked about.

Adoor's moustache isn't thick, but is very carefully groomed. It used to once curl up at the ends slightly but now appears fairly linear. His utterances are modulated as they pass through the meshes of his moustache, before they finally reach our ears.

The sincere moustache, though, is not available to me for sampling, since this was supposed to be a telephonic conversation.

So I dial in and am greeted with the Reveal of the Year: Adoor's Caller Tune, as it broadcasts -- surprise, surprise -- Mera Desh Badal Raha Hai.

Whether he believed in its validity or not, I knew at the very instant I heard the Caller Tune that it wasn't in place by Adoor's selection.

For, Moutatthu Gopalakrishnan Unnithan had never been so explicit; not even about the strongest of his convictions. To a dense artist like him, Definitiveness of this nature must surely sound like Death.

The Caller Tune plays out thrice and he answers thrice and, thrice we make dates and go back on the decided time-slots, thrice. And between all those broken promises, a few interesting exchanges happen.

I tell him how I wanted to steer clear of all the titles he is usually bestowed with. "The Master or 'The Maestro," I propose, "is merely an evasion tactic deployed by those who want to escape the responsibility of analysing his special strengths."

At any rate, I think it's time we got hip about the man!

So how about 'Adoor the funny guy?' Or 'Adoor the black-satirist?' A largely unremarked feature of Adoor Gopalakrishnan is his pungent wit.

I find Adoor's movies brimming with some of the most painfully funny moments ever recorded on cinema. However, very much like Kafka, Adoor's humour is derived from the way he merely documents certain realities; any explanation of those realities would empty the humour of its strange magic.

To understand Adoor's 'mastery,' you need to first 'get' this aspect of Adoor's wit.

In his latest movie Pinneyum, a guest shows up at a man's door and announces: 'There's no way you would know me. I am your relative.'

The above two lines of dialogue are not meant to be uttered without a pause between them, but it is in the Malayali tradition of stacking the two unrelated lines one upon the other, that the statement becomes so poignantly funny.

In his 1978 release, Kodiyettam, a Chenda player yanks the lead character Shankarankutty away. Shankarakutty refuses to move, but the Chenda player aggressively pursues his exit, all the while playing the Chenda and grooving to the beats of the instrument.

I bring up that scene and reiterate to Adoor how funny I think his movies are, and he laughs his hearty laugh; the sincere moustache, splicing together the pools.

How about 'Adoor the badass?' Ever noticed a running theme in all of Adoor's movies: That it's his most outwardly immoral characters that possess a sense of true integrity?

Adoor was, and continues to be, opposed to the idea of easy reformism; labels are not for him, either.

'Why should I be free? Who wants Freedom?' his Basheer, in Mathilukal, had asked, and while Vaikom Muhammad Basheer had originally said the line, you can always imagine Adoor repeating it, punctuation-for-punctuation, and spirit-for-spirit.

The Good and the Bad don't get classified as separate entities in Adoor's movies as much as they get contained in each other.

What gets captured vividly is the Malayali Dream taking shape -- at week-long festivals, on the armchair, inside the jail premises, around the time of India's Independence.

And now with Pinneyum, his 12th feature film, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, in trying to decode every aspect of that Malayali Dream has taken for his subject, a perfect Malayali crime: The Chacko Murder Case of 1984, orchestrated by Sukumara Kurup and his family.

Pinneyum begins in the immediate future (A wall calendar, in the first scene, is open to October 2016). The movie is crude and, at many points, poorly constructed. The dialogue delivery is on numerous occasions, shockingly theatrical.

Adoor's penchant for maintaining a tight leash on the actors and not giving them enough scope for improvisation, robs the performances of their deserved fluidity. All the same, the movie manages to be an unforgettable experience.

Walking out, partly shaken, I realised that complaining about Pinneyum's imperfections would be like bickering over Tolstoy's 'tendency to dramatise.' The point of the work, and there's more than one point here, is far greater than its deficiencies.

I ask Adoor if the rites of love in Pinneyum, its rituals of love, veering more toward the dramatic side were his personal choice. "Like always, everything in this movie is my personal choice. There's nothing subconscious or unconscious or random, here. The drama of the romance between the husband and wife is calibrated to contrast with their eventual tragic destinies," he replies, switching between his mobile and his landline phone, between my question and his answer.

"Mobile phones tend to get too hot. You should also consider switching over to the landline," he suggests.

Pinneyum is perhaps the first Adoor movie that does away with his trademark style of using a particular character as the spindle around which the narrative turns.

Unlike in the past, when he tightly followed an Unni or a Shankarankutty or a Thommy or a Basheer, the director, this time, gives us a set of keenly observed sketches, dealing with a motley of characters and with not one character taking precedence over the other.

A friend of mine had once casually theorised that Malayalis are, on some psychosomatic level, proud of Sukumara Kurup -- they see him as somebody who beat the unjust system at its own game; and somebody who continues to do so, for 32 years now.

What Adoor wants to do in Pinneyum, is diminish the average Malayali's grand obsession with Sukumara Kurup by revisiting the case from the perspective of those who hatched the crime.

To subvert the dynamics of the case, he first destabilises its genre-like elements -- he drains its immediate thrills away; gives it a long prologue and an equally long epilogue; deadpans the act of the crime itself; and turns it inside out.

Think about it. It took a 75-year-old director to teach the reformist set of Facebook users that Evil is not an aberration, but something that resides in the most regular-seeming of human beings.

If Jean Renoir's humanity becomes evident in the line, 'Everyone has their reasons,' Adoor's humanity-statement reads, 'Everyone is entitled to their personal lapses in judgment.'

"I am always dealing with attributes, typical to Malayalis; characteristically, a street-smartness that spills over into a dangerous tendency: Of seeing the other person as smaller than themselves. The Bengalis have a word for us; they call us Chalu Jana," the voice at the other end of the phone, tells me.

Purushottaman, the protagonist in Pinneyum, commits the grave mistake of believing that if he can devise an ingenious crime plan, he must also have a natural talent for evading its consequences.

Adoor's characters have always been naturally preoccupied, too caught up in social issues, or too involved in the immediate sensual pleasures of life, to have any doubts of existential nature.

But these characters, when scanned by the writer-director's observing-machine-like eyes, all seem trapped in a certain existential crisis -- something which is also true of the family in Pinneyum.

There are other recurring Adoor touches: A general public fear for the law, brutal policemen who are chided for toning down their brutality, long shots canned from the inside of a vehicle (Don't think anybody has chronicled Kerala's roads better), and an emphasis on certain distinctive fine-motor skills of Malayalis -- tapping on the bench to seek someone's attention, exaggerated hand gestures when giving directions, and that derogatory public smirk.

In a scene, KPAC Lalitha's face contorts when twisting the clothes she is putting out on the clothesline, and it reads like a reaction to a dialogue someone just said, and not as an involuntary act.

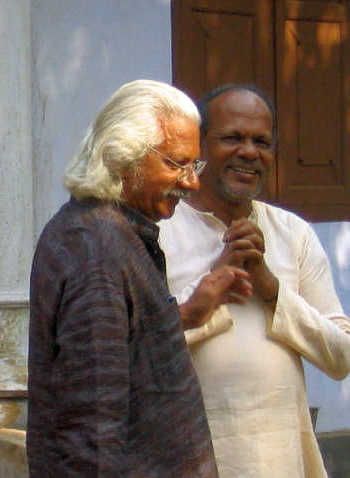

A scene from Adoor's Anantaram.

A scene from Adoor's Anantaram.

If Adoor's movies are individualistic, it's due majorly to such observations that only he could have made.

"Let's talk about Sex!" I remind Adoor that while he has never photographed a single lovemaking scene, all of his movies betray a profusion of sexuality: Dormant sexual feelings; the Animalistic verus the Refined and the sexual tension that that contrast dissects; and sexual frustrations that show up as domestic frustrations.

In Pinneyum, the complaining wife punishes her husband by making their daughter sleep between them. 'You can join us on the bed, but only if you behave well,' she states.

Why is Adoor such a 'tease?' I hear his laugh once more, as he says "I have talked about this before, but sex is beautiful only when it's hinted at. I want my audience to complete the ceremony of sex in their own heads."

Much like that bed scene in Pinneyum, women have, in all of Adoor's movies, wielded a domestic power that makes puny, the street strengths of the men; in the way they sit, in the way they look at their men, in the way they mock at them, and in the way they straighten them out.

Now that we're racing, I bring up the topic of pacing. I put forth my theory that unlike movies that offer audience syrupy diversions from life, Adoor -- in the way he paces his narratives -- perhaps intends to make his audience walk out with a heightened awareness of the poetry that resides in ordinary life.

He agrees, but doesn't laugh. I bait him with something Kiarostami had said: That movies that allow its audiences a good nap at the theatre are, maybe, more considerate than movies that build up in them, unnecessary expectations from life.

He terms it, an interesting theory, but one that isn't applicable to him. "I'd rather have the total alertness of my audience."

My phone battery drains off yet again, but only after I've replied to his query of whether there was a substantial crowd for Pinneyum, in Mumbai. He enquires if I had tagged my family along for the show. I inform him that my kid wasn't keeping well.

"I would have loved it, if you'd watched it with your wife," he says, and exhales slightly. ZILCH AND OUT!

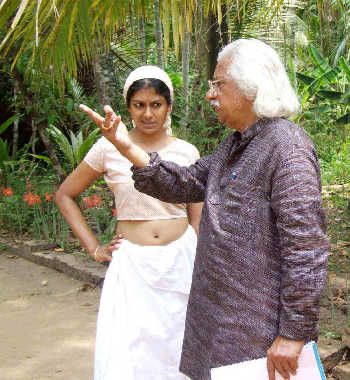

Adoor Gopalakrishnan directs Nandita Das.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan directs Nandita Das.

I don't ring up Adoor again, although I had a series of questions for him: About how, after revolutionising the usage of sound in Indian movies, the auditory aspects in his movies had now thinned down considerably; about why, despite his hyper-emphasis on realism, he still harbours an aversion for overlapping dialogues; about the loss of his professional sounding board -- his preferred cinematographer, Ravi Varma -- and the demise of his personal sounding board -- his wife; about how does he -- a teetotaller to my knowledge -- know so much about arrack shops in Kerala; about whether, he was aware of a new-generation of filmmakers like Dileesh Pothan and Rajeev Ravi who were making popular movies, but with the same attention to detail that he and K G George had once displayed; about how it's always said that cinema is essentially a 'Young Man's Medium' and if he did feel, at least occasionally, the bubbles in his blood, during the making of his latest movie.

Some questions, I realised, may have disconcerted him and others I knock off, for they wouldn't be suitable for a telephonic interview.

Most of the questions, however, I keep to myself, because it hit me suddenly that the essence of Adoor's movies were always in their unanswered questions.

As it was the case with the teased-out sexual feelings,the narratives of his movies are perhaps meant to be completed only in the viewers' heads.

Twelve feature films and three telephone calls later, what started out at the moustache had ended with an honest exhalation.