One of the most prolific music composers that the Hindi film industry has come across, Rahul Dev Burman was a force to be reckoned with. His hip and catchy tunes from the 1970s and the 80s transcended generations and are still popular.

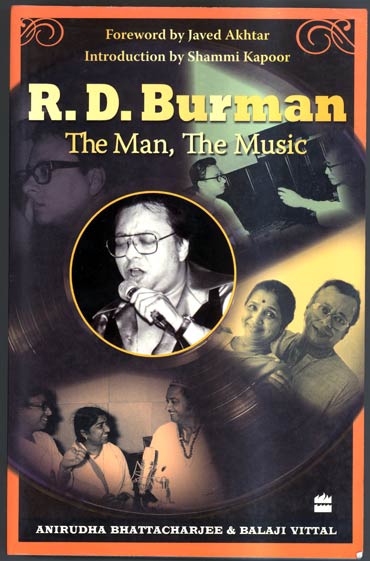

But we barely know how Pancham Da , as he was lovingly known, composed those famous tunes. Thanks to authors Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal, we get a sneak peek into how some of the classics were composed.

We present an excerpt from the book, R D Burman: The Man, The Music written by Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal.

Being a virtually toll-free market for ganja, Kathmandu was the obvious hippie haven. The hippies' cavalier lifestyle and outlandish appearance jarred against the tranquility of the terrain, yet interestingly blended into it. The expanse of the Himalayas not only accepted the contrast but also embraced these troubled children.

One such child was timid Jasbir (an unusual name for a girl of non-Sikh parentage). Spooked by images of domestic violence and her parents' impending divorce, hers was a classic case study of a child deprived of stability and self-confidence.

Dev Anand, in his autobiography Romancing with Life, reminisces about meeting an Indian girl named Jasbir/Janice in the Bakery, Kathmandu, an (in) famous hippie den. The girl had travelled the hippie trail all the way from Montreal to Kathmandu in search of peace in the mystic East, seeking solace in marijuana, hashish, LSD and the companionship of like-minded parvenus.

It was a story for a potentially great film.

Excerpted from R D Burman: The Man, The Music by Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal, Harper Collins, with the publisher's permission, Rs 399.

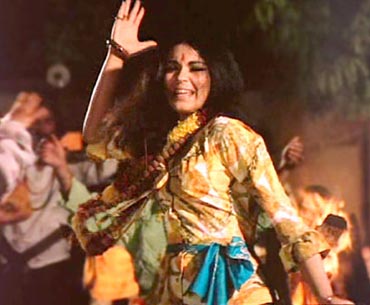

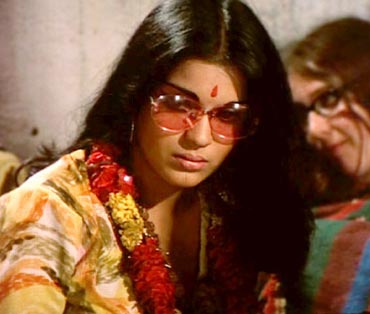

Dev Anand brought Jasbir's story to the celluloid screen in Hare Rama Hare Krishna (1971). It would give India its first pin-up icon. Zeenat Aman, having made her debut in OP Ralhan's Hulchul, would become a star, courtesy the songs in the film - Dum maro dum and I love you.

Singer Usha Uthup remembers: 'The Navketan unit, including Dev Anand and R D Burman, had come to listen to me singing at the Oberoi, Delhi, in 1969. After the show, Dev Anand asked whether I would like to sing in his forthcoming film Hare Rama Hare Krishna. I was all of twenty-one and naturally excited. The song Dum maro dum was conceived and we went into major rehearsals. It was to be [sung] as a duet between me and Lata Mangeshkar, with me singing for the bad girl and Lata-ji for the good girl.'

Surprisingly then, Dum maro dum ended up as an Asha Bhonsle solo.

'Pancham expressed regret, but with the trademark quote, "Yaar, kuch kartein hain", added that he had another song in mind for me,' Usha carries on.

Pancham kept his promise to Usha with I love you which was designed as a duet with Asha Bhonsle singing for Zeenat and Usha Uthup for another girl in the gang.

How would Dum maro dum have sounded with Lata Mangeshkar's trifle shrill voice and Usha Uthup's canyonish contrast? Post the decision to turn it into an Asha solo, Pancham probably had to colour the song differently as the voices of Lata and Asha are very different. An Asha Bhonsle track like Dum maro dum had to have a blend of sultriness and wildness. Recorded in a number of versions and used in bits and pieces in the film, the song became the anthem of the hippie generation with its psychedelic view of life and anti-establishment convictions.

In the song, through the smoky haze, one makes out silhouettes of youngsters in a swagger. . . and the only sober man in the den has his mouth pursed and head disapprovingly cocked to one side.

It is interesting that despite the song's volcanic popularity, Dev Anand kept just one stanza in the film when it was first used in the film. Dum maro dum is followed immediately after by the Kishore solo Dekho o deewano. 'Using both the stanzas might have diluted the brother's entry as the second one was repetitive,' says he. The Long Play record, however, carries both the stanzas and has classified the two songs as discrete tracks.

I love you, the Asha-Usha duet, was like an 'extra cheese' version of Dum maro dum. Asha held her own with the treble, and Usha resonated an octave lower. Front-ended with an outdoor picturization presenting downtown Kathmandu by night, Pancham allows Usha Uthup to take over the extended tailpiece of the track as it picks up speed and shifts a note higher to 'We go a l'il faster man'. 'I love you' was, in chronicled memory, the first-ever bilingual song in Hindi cinema.

The contrast in styles between Usha and Asha shattered the Indian paradigm that female singers had to have a sharp and shrill voice. With singers like Khursheed Bano migrating to Pakistan during the partition, the idea of women singing light music with a baritone was inconceivable in post-independence India. Till Usha Uthup dared to change the norm. She introduced not only the Western bass but also the correct intonation of English words without the fake accent. For all their talent, the first family of female singers in India were lacking in that particular department. To hear 'I love you' blaring over loudspeakers in metros and small towns close on the heels of Dum maro dum was a part of growing up in the 1970s.

Lata Mangeshkar as the voice of the good girl in the first flush of womanhood was accompanied by Kishore Kumar in the delectable 'Kanchi re Kanchi reo 'O re ghunghroo kaa bole re, a Lata solo, was shot with half the population of Bhaktapur gathered around to watch Mumtaz as she danced to the tune for three days, the duration of the shooting. Apart from the tabla and mridangam, a new percussion sound was heard in the song for the first time in Hindi film music. Until then, it used to be the duggi, but with these two songs, Ranjit Gazmer and his madal joined RD's coterie. Pancham aptly named the Darjeeling boy Kancha, and he still loves to be addressed that way. Ranjit 'Kancha' Gazmer gave the composer a new sound that he used in many compositions that followed. Kancha too is an independent music director, having scored music for over a hundred Nepali films.

The recorded version of 'Kanchi re Kanchi' starts with Kishore Kumar humming. However, Dev Anand preferred to film it otherwise and the song appeared in the film without the humming. Pancham later said that this was one of the tunes that came to him in his sleep, almost in a dream.

The song 'Phoolon ka taron ka' was Pancham's first duet with Lata Mangeshkar. He lent his voice to Kishore Sahu, an actor and director, albeit only for two lines, while Lata brilliantly modulated her own to sound like a ten-year-old boy, Master Satyajit. A brother-sister reunion makes for a very unusual climax. But here it was with the adult version of 'Phoolon ka taron ka' sung by Kishore Kumar, with Bhupendra and Charanjit Singh on twelve-string guitars, and profound lyrics by Anand Bakshi: 'Jeevan ke dukhon se yun darte nahin hain/ Aise bach ke sach se guzarte nahin hain / Sukh ki hai chah toh, dukh bhi sehna hai'.

Though Pancham would at times get irritated by Bakshi trying to impose his tunes on Pancham's, he also complimented Anand Bakshi as a super lyricist in one of his interviews.

The job of composing for Hare Rama Hare Krishna came to Pancham after the theme failed to appeal to his father. According to Dev Anand, 'Dada Burman did not like the theme of hippies and brother-sister relationships. Pancham was given the opportunity and he grabbed it. He completed the tunes of this film in two weeks flat. With this film, Pancham's career really took off.'

Apparently, Dev Anand had first offered Jasbir's role to Zaheeda, his heroine in the film Gambler (1971), but she turned him down. Her decision won her more public gratitude than any popularity she might have gained had she accepted the offer. Zeenat Aman, Miss Asia Pacific International 1970, revolutionized the image of the female lead from the amplehipped, delicate lady to the svelte, slim and coolly urban woman who was bold enough to walk the ramp in thigh-length haute couture. She became the first-ever reigning fashion queen to sashay into Bombay filmdom and changed how the Hindi film heroine would be perceived for all times to come.

As far as the music was concerned, the Navketan baton had passed safely from father to son.