Titli is a solid directorial debut but it could have been so much more, feels Raja Sen.

Titli is a solid directorial debut but it could have been so much more, feels Raja Sen.

There's a world of difference between red and maroon.

You might not expect him to know that distinction, but Vikram does.

A security guard at a mall who moonlights as a carjacker, Vikram is furious at that very fact: that you think he doesn’t know better.

In one of the finest performances I’ve seen this year, Ranvir Shorey is spectacular as the elder brother in Kanu Behl’s Titli, the story of a dysfunctional family of bottom-dwellers. It is a performance of rage and nuance, of unexpected tenderness and misplaced nobility, and bloodthirsty cynicism. Shorey nails it, and it’s hard to take your eyes off Vikram.

Behl’s film, however, is not about Vikram.

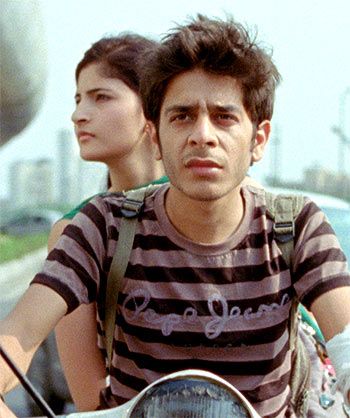

It is about the youngest of three brothers, Titli, a kid scrounging up to buy a parking-space in a shopping mall, looking to some kind of future away from the hellhole where he lives.

As setups go, it’s super, and Behl -- shooting on 16mm film -- gives us a sparsely coloured, visually impoverished movie.

Behl has the look right and his ensemble is impressive, but the film itself suffers from too much navel-gazing. Too much time is devoted to purposely phlegmatic meditations and too little on fleshing out actual characters, showing us how they tick.

We are pointed to characters and their contradictions but -- save for Shorey’s Vikram and Shivani Raghuvanshi’s fabulously acted Neelu -- they are not explored beyond their helplessness. There is no acuteness; all we really know about them is that they are all miserable. And the narrative, almost sadistically, impels us to suffer along with them.

For a film that takes pains to looks realistic, it hinges on too feeble a plot, a raise-money-in-limited-time wheeze that could have been done in many ways, like in Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels fashion or, given producer Dibakar Banerjee’s work, like in his resoundingly magical Khosla Ka Ghosla.

Titli does very boldly to eschew both comedy and style for a more arid approach, but the narrative rationale is flimsy: What, for instance, is happening to the money from all the carjacked cars?

Shashank Arora, who plays Titli, does so with the right kind of world-weariness and has enough hunger and desperation in his eyes -- and, it must be said, on his frame -- but his Titliness isn’t given enough rein. He goes through the film wearing the same expression of bewildered blankness, and while that inert nothingness is becoming fashionably confused with top-notch acting in Hindi cinema these days, it doesn’t help flesh out the character. He does erupt for one moment of white-hot rage later in the film but it, appearing so abruptly, serves more to derail the film than anything else.

Arora isn’t a bad actor and wears his inscrutability consistently, but a film like this needs a preternatural talent tugging it along, someone meteoric and jawdropping, like a Gael Garcia Bernal maybe.

Or, in the absence of that, Shorey in the lead role. Now that would have been a helluva movie.

It’s a pity because this is a fine, thoughtfully crafted film.

Siddharth Dewan’s cinematography is voyeuristically intrusive, with some strikingly poignant compositions highlighting the film’s authentic art-direction.

There is a moment, for example, when Titli is on a horse, being led to his marriage. The horse looks as unwilling as Titli, as the green frame shows us the horse, Titli and the disinterested child made to sit in front of him on the saddle, passing in front of a storefront sign for Seth Medicos. In this world, even a baaraat is not allowed the grandeur of escape.

Yet despite these deft visual nuances -- the dotted bandaid-knockoff on Vikram’s hand, the bypass-surgery scar on Titli’s father’s chest, the way said father (Lalit Behl, the director’s own father) scoops his sabzi into the roti -- the film begins to feel indulgent as it keeps showing them off.

Pauses between conversation seem reasonable in isolation, and are well-written, but when stacked one atop another as they are in this film, they begin to feel tediously long.

Nihilism and bleakness lend themselves well to cinema, but there needs to be something compelling for the audience: Titli errs on the side of the comatose.

In its admirable refusal to steer clear of style -- or, indeed, obvious entertainment tropes -- it is often too bland and, by the end, too long.

Fleabitten characters aren’t the problem at all; just last year, Anurag Kashyap’s Ugly was made up of even more unsavoury characters, but it was impossible to look away from the screen.

Titli offers up dry nakedness as if that is enough to impress.

In many a scene it is -- and, don’t get me wrong, this is a stirringly solid directorial debut -- but in many a scene it feels too intentionally underdone.

There is a scene, for example, where an arm is broken. It is a strongly scripted moment but, while intending to shock us, the film looks away too easily. It starts off with searing intensity, hits peak when there is an alarmingly casual plea to stop the breaking, and then peters off into not merely a tame hammer-wound but, alas, a scene that loses its momentum.

The actors work the scene sincerely but it could have been so much more.

Instead, Behl chooses not to look away when a character throws up in a sickeningly long scene, so long it feels gratuitous.

Because there’s a difference between showing the retching and the wretched.

Rediff Rating:

© 2024 Rediff.com -

© 2024 Rediff.com -