Piku is a film with tremendous heart, raves Raja Sen.

Piku is a film with tremendous heart, raves Raja Sen.

We are never told Deepika Padukone’s actual name in Piku.

A Bengali nickname is an all-conquering wonder, a sticky and stubborn two-syllable sound that a person is straddled with when too-young-to-object, and one that follows us to our graves.

And so Deepika’s character -- be it in office or living room or on a relative stranger’s phone-screen -- is always simply Piku, and, despite the peculiarity or cuteness of the nickname, its usage has become matter-of-fact.

The fact that throughout the film, we never dwell on its etymological origin-story and aren’t concerned with what Piku means (or may perhaps be short for) illustrates honesty and a storytelling confidence rare to our cinema.

Shoojit Sircar’s Piku is a special, special film.

It is a film about a cantankerous old man grumbling about constipation, a film about a young girl who knows how to drive but chooses not to, and a film about a young man who just can’t bear his mother.

It is a film, then, about families and their foibles, about the small and large obsessions and habits that single us out for who we really are.

It is a film with tremendous heart -- one that made me guffaw and made me weep and is making sure I’m smiling wide just thinking about it now -- but also a sharp film, with nuanced details showing off wit, progressive thought and insightful writing.

Take a bow, Juhi Chaturvedi, this is some of the best, most fearless writing I’ve seen in Hindi cinema in a while.

Unlike Piku, her father has outlived most folk older to him -- the people who would have called him by a nickname. And yet Bhaskar Banerjee insists on a unique spelling, a Bhaskor to differentiate him from the Bhask-err types he might encounter near his Chittaranjan Park residence.

Bhaskor-da, frequent follower of laxative advice and incorrigible salt-stealer, is an imperious old coot fervently obsessed with his bowels.

This may or may not be a Bengali preoccupation, for ours is a tribe where mothers and wives glug Isabgol side-by-side before bedtime or, as I grew up witnessing, grand-uncles spend their mornings hopping about in the hope of generating the elusively mentioned “pressure.”

All this, we’ve always been told, is not propah conversation.

It is too intimate, too familial a topic to be discussed out loud or far away from the toilet.

Chaturvedi and Sircar, however, clearly have a strange love for ‘bodily fluids’, and after making the nation titter about sperm in Vicky Donor, they take shit head on with this fine film.

Unlike Mr Banerjee’s motions, the laughs come quick and fast. Yet scatology is merely one affectionate used aspect of Piku.

There is a road trip, there are arguments, there is affection, and all of that I leave for you to discover. This review is, besides applause, merely a celebration of detail and of craft.

Bachchan, as Banerjee, is a delight, hamming it up in the way old Bengali men do, posturing for family and servants and wagging his finger reproachfully at those outside the clan -- at one point he calls Irrfan “you non-Bengali Chaudhury.”

He appears brash and dismissive but this, as he says, is because he is “a critical person”, which translates to him setting higher standards for those he loves.

He’d be an old-school patriarch if he wasn’t such a vociferous women’s-libber, one who champions his daughter’s sexual independence.

Having said that, he remains so set in his ways that he sits in Delhi and relishes a month-old stack of Calcutta newspapers. It may be old news but it’s the news he loves.

Irrfan Khan is characteristically flawless. Despite a less author-backed role than father and daughter, he imbues his character with enough authenticity to steal many a scene and give the narrative its consistency.

It is largely for the benefit of Khan’s Rana Chaudhury that the Bengalis speak in Hindi and English through (most of) this film’s duration, and the character is fascinating.

An engineer with a dodgy backstory, he’s morally sound enough to berate a pearl-pilfering sister and feels the need to call out selfishness even in someone he likes.

Khan’s performance holds the film together, balancing the diametrically opposed -- and fundamentally similar -- father and daughter, sometimes by just a truly pointed look.

One scene, where he glances at Deepika to necessitate a change of seating arrangements in the car, is an absolute stand-out.

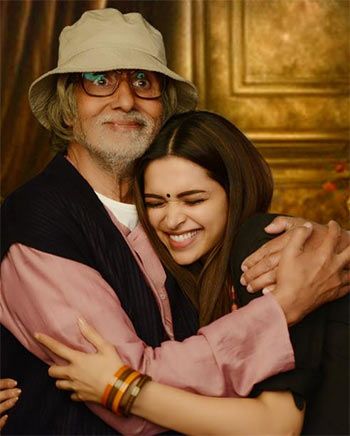

Padukone is at her very best, the actress moving farther from her contemporaries with almost every successive film, and here she stuns with her casual body language and her inch-perfect intonation.

She’s impatient and short-tempered, wearing her otherwise-adorable dimples dismissively, like a no-nonsense shield.

She knows when to prescribe homeopathic pills, and goes into enough graphic detail on the phone to wreck her dates.

This tightly wound Piku is a demanding part, and the film pushes her.

She rises to the occasion, and her performance -- which believably oscillates between a defiantly uppity woman to a girl half-proposing marriage with a mouthful of egg-roll and a giggle -- is spectacular.

And, as if that wasn’t enough, Sircar makes Padukone say ‘pachcha.’

Piku uses this Bangla word for arse -- a cute splat of a word, with a tchah-sound built right in -- while at a dining table full of eagerly nostalgic relatives and Padukone plays the moment magnificently, her eyes twinkling and grin well in place, dropping her guard to say an ‘uncouth’ word and, simultaneously, thrilled to be saying it.

Bravo.

The ensemble cast is spot-on, from the smug self-celebrating aunt played by Moushumi to Raghubir Yadav’s doctor, who thinks nothing of ordering a few dozen boondi laddoos from an utter stranger, and it’s lovely how Sircar uses them all.

Just like he does Calcutta, making the city look big and sturdy and historic and, well, epic, without ever picture-postcarding it or resorting to obvious cliches.

Except the cliches spouted by old Bengali men, pleased as punch to see their kids remembering old addresses long forsaken. (While on that, here’s a joke Bengali fathers will appreciate: “What are bowels? Things that hold up many conshonants.”)

There is an awful lot to love and appreciate in Piku, and, like the best of films, it sets you thinking but doesn’t rush to point out quick-fix answers.

“Not satisfactorily,” like Bhaskorda reveals when asked how well a new bowel-coaxing remedy worked, “phir bhi kuchh naya karne ko mila.”

Sometimes the joy indeed lies in trying out something new, and Piku is just the tonic.

Rediff Rating: