While filled with startling insights and questions, and buoyed by terrific performances throughout, Newton suffers from a lack of end-to-end clarity.

It is a near-great film, but one that for some reason doesn't express itself fully, feels Sreehari Nair.

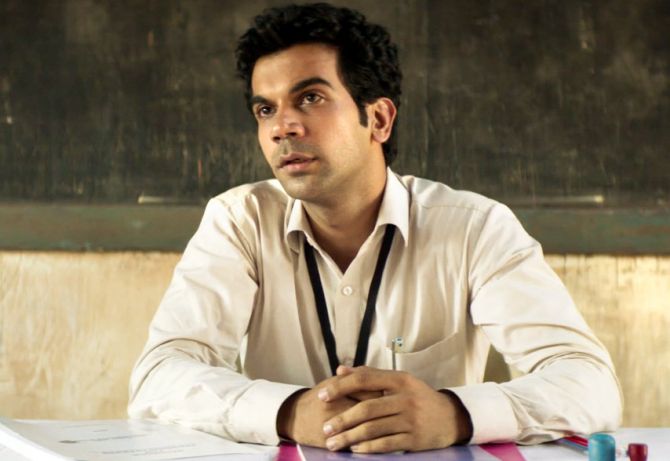

Rajkummar Rao's Nutan Kumar is small and stubborn.

Inside his head, there seems to be so much electricity that it has given his hair a permanent curl.

The electrical impulses multiply when he is pushed to the wall, resulting in exaggerated blinking and a conscious scratching of his shoulder.

He is also his own legend (the title of the movie is his personal reworking of the name his parents chose for him).

And before the press proclaims him a hero for our time, be aware that he is essentially a by-the-book idealist -- not very inventive or intuitive, and maybe even a little dull.

As the central character in Amit Masurkar's Newton, Nutan Kumar presides over the voting process in a Naxal-dense town in Chhattisgarh like a Japanese railroad engineer trying to bring order to a world of Indian babus.

When he asks his team members to clean up a ramshackle polling station, they react as though he has shouted fire in a crowded theatre.

This Newton may very well be a modern-day great, but he clearly is no fun!

To understand and appreciate Nutan Kumar (Newton) you must first assent to the idea that he is the least colourful character in a movie dedicated to him.

This take on idealism is at the core of Newton.

Amit Masurkar, the young writer-director, seems to be suggesting something original, but also depressing: That an idealist in today's world does not risk death or persecution as much as he risks being classified as a 'bore'.

Poor Joan of Arc was burned at the stake for not giving up on her ideals. In today's time, she would probably have been punished with a diminishing social circle, and lonely weekends.

It is worthwhile to note though that life may have been even tougher for an idealist like Newton had he been an artist.

In a 2003 interview, author David Foster Wallace had talked about Citizenship and how being a Citizen means 'understanding your country's history and the things about it that are good and not so good, and how the system works, and taking the trouble to learn about candidates for political office'.

Wallace had started off on his mantra, but copped out suddenly: 'Talking about this now, I feel ashamed, because my saying all this sounds like an older person lecturing, which sets me up for ridiculing.'

The total absence of such a second consciousness -- the kind that Wallace invoked in the middle of his speech -- is a blessing for Newton.

A clerk by profession, Newton knows that he is in line to be sent off for Election Duty in a Naxal-heavy area but his only concern is with neatly completing the task at hand; it's only the nitty-gritty of his work that matters to him, and not what surrounds it.

He is lectured on the practical and the spiritual aspects of his duty by a mentor (Sanjay Mishra, in perhaps his shortest movie role yet).

Mishra's hands assume rectangular poses, he converses in the Socratic Method, kids Newton about his name, and puts forth the theory that his namesake, the scientist Isaac Newton, was probably the world's first true Socialist (Reason: With his discovery of gravity, Isaac Newton had equalised every form on earth).

Rao's Newton is stiff but dogged, and he ends up making the trip to the tribal village.

Here he encounters an intelligent, ill-tempered commander, Aatma Singh, and spars with him all the way through.

Singh, played by Pankaj Tripathi, walks the beat in the godforsaken village, and his ideal day would be one where there are no civilian casualties to report.

When the full of beans Newton thwarts Aatma Singh's plan of leading such an ideal day, Singh immediately orders for bulletproof jackets and ballistic helmets: He knows that one look at those things is enough to test a regular man's cojones.

As they walk the jungle, with wireless messages and landmine detectors filling their immediate environment, and as they pause for rest, Aatma Singh stays behind Newton eyeing him suspiciously: He wants to decode him, but can't.

Newton and Singh are joined by a group of security force personnel (a mix of military and local recruits with their own internal frictions); two public service officials, one of whom is Loknath (as played by Raghubir Yadav, he is what happens to a poet when his love goes unfulfilled); and a local lady Malko (a brilliant Anjali Patil who seems to be carrying the entire history of her land on her face).

The movie is about the interactions that happen within this closed ecosystem over one voting day.

Soon, the tribal folks in the village also join the merry band at the polling booth, and the interlocking tensions become a preview of the confused state of our democracy.

Amit Masurkar knows that the way to set off the pillar-of-rectitude Nutan Kumar is to surround him with characters opposed to his righteousness, but gifted with the same level of human intensity.

This intensity is the strongest in Pankaj Tripathi's Aatma Singh.

For the last two years or so, Tripathi, with every role, seems to be moving farther away from the spoken word.

He is clearly aiming for a sculptural refinement that the greatest of actors often aim for: where you pride yourself in bringing a movie frame alive just by appearing in it.

When a shapeless phrase at the centre of Newton threatens to disintegrate the picture, it is Tripathi who gives it the much-needed solidity.

Even through the running show of antagonism, like when he shuts Newton down by uttering the word 'Rules' with a smile, you can sense a paternal relationship developing between Tripathi's Aatma Singh and Rao's Newton.

Their spars seem like a replica of the fights that Newton has with his father who is pained by the sudden realisation that his son has outgrown him. Tripathi, working with Rao, recreates that domestic tension in the sun-drenched jungle.

There's always more going on inside Aatma Singh, more feeling bubbling up inside him than he says, so when he finally opens his mouth, the irony in his lines hit you hard.

In one scene, he cracks a joke about how, even the hens in the Naxal-land are imbued with revolutionary quality, and that it takes two hours of questioning for one egg to pop out.

In another scene, he bites into a piece of beetroot with a cry of Lalsalaam.

Tripathi doesn't turn Aatma Singh into a hollow cynic that Newton can beat down -- he gives him force and echoes.

The film also needed a middle-class windbag with annoying patterns of behaviour with whom Newton can butt heads, and Raghubir Yadav's Loknath steps in as a man with belief in occult powers.

Loknath talks like one of the witches from Macbeth; he's a myth-maker who is writing a novel with a plot that sounds like a Bunuel movie infested with zombies.

Loknath believes that consumerism is the real solution to fighting the Naxalite movement ('Give those revolutionaries Colour Television sets and that'll calm them down,' he says at one point).

Toward the end, when Rajkummar Rao stages a rifle-dharna, Loknath pauses for a second: He is clearly moved, transformed a little, but Raghubir Yadav being the master performer that he is, underplays that scene.

Newton isn't a movie of answers, but tough questions.

One of the things the picture gets at, by presenting to us one of the grimiest microcosms of democracy-in-motion is: How do you explain Public Will to a set of people who are only used to being ordered at?

Democracy, as you may know, was originally conceived for only a small population.

How then do you successfully adapt the fixed principles of democracy to a land that changes colour and fervor many times in every few kilometres?

In the film's best scene Newton tries to explain to a high-ranking police officer why the entire day of voting was an exercise in futility, and the officer cuts him off: 'Was there an instance of booth capturing? Of fake voting? We then are looking at a peaceful election, aren't we?'

Democracy defeats Newton at his own game. He may do well to revise what the wonderful Malko had told him: 'The history of the jungle is older than the history of democracy.'

Amit Masurkar has a vision for the banal, and that is also his technique.

He isn't going for a show of technical virtuosity but working to preserve the structure of his narrative. His camera hardly moves and the effects of satire are achieved majorly through editing.

In one sequence, Rao's Newton looks at a Ballot Box, and the Box seems to stare back at him.

When Malko narrates the name of the political candidates, Masurkar cuts to scenes of their marketing strategies: It is the rural marketing of bad tastes and shallow promises running together.

In a stretch of broad but effective satire, Masurkar fills frames upon frames with faces of frail-looking Adivasis, all showing us their ink-marked 'I just voted' fingers.

This is the much-enacted social media ritual of celebrating one's vote given the tribal twist: There's the showiness one associates with the act, set here to rousing music, and it contrasts beautifully with the cluelessness of the Adivasis who have no idea what they have just done.

As the movie progresses, Newton himself realises that he knows more and more, but understands less and less.

And the picture is written and made in much the same spirit -- not by a man of sustained knowledge or worldliness, but by a man in a state of shock; it feels as though Amit Masurkar (his first movie was the flaky but charming Sulemaani Keeda) had gone for a trek and had come back a sage.

Masurkar's personal shock in discovery accounts for both the magic of Newton and its lack of end-to-end clarity.

Like for example, we hear a lot about the terror of Naxals, but learn nothing about their passion.

And when Newton fails to convince us as a fully-developed protagonist, the picture falls back on the middlebrow theory that the country would do better if we all did our work well.

In its tone, texture and in the way certain scenes are mounted, I found Newton close to Dileesh Pothan's Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum, but what Masurkar lacks is Pothan's innate talent for conveying the general through the specific -- his effects are at times too hard edged, and when he tries for subtlety, he doesn't express himself fully.

Rajkummar Rao is brilliant (as he often is) but in an effort to strip him off an idealist's usual platitudes and sloganeering, Masurkar makes Newton distant: We are never inside him.

Does he see his role as a mini act of nation-building or is it a 'just doing my job, ma'am' kind of thing for him -- the movie suggests both possibilities and they cancel each other out.

When his eyes well up, is he crying for the state of the nation or the death of his ego -- it never quite becomes clear to us.

The elite liberal class will be out tomorrow shouting: 'This the kind of man the country needs!' But to expect a country of Newtons is to reduce the spectrum of personality-types to a new narrow: From the Featureless to the Fascists.

You can admire the man from a distance, but will you invite him to your house party?

The true message of Newton, I think, isn't that one should try to become like Newton, but that one should understand that there is a greater degree of complexity in everything one sets out to improve.

In a scene that has Newton trying to explain the importance of voting to the Adivasis, he says, 'The person you elect will represent you in Delhi'.

At this point, an old guard, a crippled soul with little Nosferatu hands and shaggy clothing, suddenly rises up from his pallet and announces, 'I am the leader of these people, and I will go to Delhi.'

The picture wants you to craft change, but it first wants you to give up on your fantasies of quick and easy change.