Alexander Payne’s new film, Nebraska, is a stunning meditation on the ghostliness of America, raves Raja Sen.

Alexander Payne’s new film, Nebraska, is a stunning meditation on the ghostliness of America, raves Raja Sen.

Uncle Albert likes to watch the road.

He takes a weatherbeaten deckchair and kicks back after meals, sitting by the side of the road to watch cars go by.

It doesn’t seem that absurd a pastime for a man so grey and wrinkled he predates the television set, and one whose brothers bicker endlessly about whether one of them owned an Impala or a Buick 40 years ago.

While on that, is ‘bickering’ even the appropriate word for conversation so comfortably wound down, so slow, conversation made for the sake of hearing one’s own voice, talk that staves off atrophy?

The problem with Uncle Albert’s plan is more immediate than existential: there are no cars on the road he’s watching.

Alexander Payne’s new film, Nebraska, is a stunning meditation on the ghostliness of America, on how farflung towns that churn out the country’s cars and crops have dried into pensioner-populated nothingness.

Their children have abandoned them for jobs and prospects, and for cities that look better in colour; here in Hawthorne, even the bartenders are wrinkled.

It’s like a lawful Old West, where a man without bifocals assumes charge and pronounces himself sheriff. The town is fictional but Payne’s vision achingly universal; we all know people who live in ghost-towns, even if they literally live next door.

One of these folks is Woody Grant, an old drunk with an astonishing gloriole of hair. It’s as if Doc from Back To The Future picked gin over science and stuck his finger into too many light sockets.

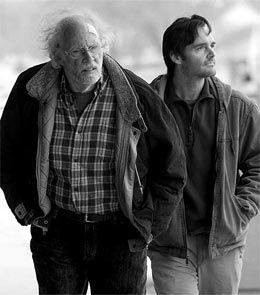

Shot as the film is in gorgeous black-and-white, the tufts frame his head like scraps of a candyfloss cloud. When we first meet him, Grant is walking -- shakily but steadily, lost yet determined -- on the highway, from his Montana home towards Nebraska, convinced he’s won the sweepstakes. It’s one of those magazine subscription scams, as his son exclaims, but Woody has bought into the declaration that he’s won a million dollars. And so he walks.

Woody is hard-pressed for any support, from facts or family, but that son, David -- living a despondent life selling stereo equipment he admits is all the same nowadays -- decides to indulge the fading father’s whim and drive him to Nebraska, give him a last gasp at hope. Woody’s wife and other, more successful son disapprove of this impracticality, but David sets off with his mulish dad, desperate, at the very least, for any enervation.

Played by Bruce Dern, Woody is both inscrutable and irresistible. He teeters occasionally on the edge of dementia, but shines enough sudden lucidity to make ours a highly unpredictable ride.

Is he ill-tempered or is he a man who belongs so wholly to another time that he can’t help but alienate himself from the people around him? Dern is magnificent, with a performance so disarmingly free of artifice that it becomes hard to remember he’s acting. His motivations are too simple for us to comprehend, so we’re better off marvelling at their basic nature, and the veteran actor milks the pauses masterfully.

His lines are delivered in a gruff, no-nonsense way but the sense of timing behind them is immaculate. Payne’s film demands the viewer wait and wait and, after some paint has prettily dried, throw out a perfectly sharpened line, and Dern -- who is given the bluntest, least syllabic of these lines -- handles them so well it’s poetic.

June Squibb plays his wife, Kate, a hard and haranguing woman who constantly decries him. It is a brutal role with the toughest of lines, and Squibb makes it work with both vitality and credibility.

As David, Will Forte is so, so good with his soulful, tender portrayal of a son desperate to break through his father’s war-hardened shell. Forte looks at Dern with heartbreaking anguish, ever ready, ever hopeful, ever frightened. In cinematographer Phedon Papamichael’s strikingly lit black and white frames, the young Saturday Night Live comic looks to have all the grace of a vintage leading man, with a certified movie-star face.

Papamichael’s frames are things of beauty, and Payne broods dramatically on them. The roads look large, endless and mostly deserted, unclogged arteries of an underpopulated nation. Mount Rushmore looks as unfinished as Woody dismisses it to be, and the light outside the Blinker Tavern is the most beguiling beacon of hope you’ll see on screen in a while. And all the faces drip with character.

This is a very special film, possibly the least contrived among this year’s Oscar nominees.

Like the conversation between Uncle Albert’s brothers, Payne’s direction is so spectacularly unhurried, he eases us -- nay, lulls us -- into the moment before springing up the punchlines. For this is indeed a very funny film.

As Steve Allen said, Tragedy is Comedy plus Time. Payne, by giving us so much breathing room, makes the comedy feel more profound than it is. In the end, it doesn’t feel like an epiphany; it feels like life. You know what’s coming, but you aspire for more -- and, if you’re lucky, find it in the unlikeliest places.

The hint lies in the choice of colour. Nebraska is not merely a black comedy, but one laced with light, with hope, with brightness. Black and White, then. Sometimes they do make ‘em like they used to.

Rediff Rating:

© 2025

© 2025