'This is a film that trumpets out its sex -- it is content in being a girl's version of the archetypical boy's locker-room picture.'

'This is a film that trumpets out its sex -- it is content in being a girl's version of the archetypical boy's locker-room picture.'

'And if it was just that, that would have been fun too, but Lipstick Under My Burkha doesn't want to affect your senses, it wants to control your mind!'

Sreehari Nair comes away unimpressed.

The biggest disappointments of Lipstick Under My Burkha are its sex scenes.

Devoid of any heat, photographed in the most unimaginative manner, and 'calculated' to a fault, the sex scenes in Lipstick Under My Burkha have the power to wean both women and men off sex. (Because it can have this same effect on both genders, the film does make a unique case for Gender Equality after all!)

And therein also emerges the shallowness of this film that turns women's liberation into a dissertation topic and infuses it with no feelings whatsoever.

This is a movie that wants its revolutions, but is not willing to go through the grind -- by the end, by virtue of a cycle of mechanised carnality and tokenisms, the women are indeed liberated, but what they are liberated from is sex itself.

Despite all the claims it makes about a woman's right to express herself completely, this is an apologetic film that doesn't even know how to frame a woman's body; it isn't generous or airy enough to just let a woman be, and take over the sequences.

2015's Angry Indian Goddesses was -- for three quarters of its length at least -- a sensual, fluid movie that showed us how women behave in their most private moments, how they confront their vanities, how their bodies move in relation to each other. And that was directed by a man!

Here, writer-director Alankrita Shrivastava replaces the bodies with a series of tattered novella covers, and then waits for the applause. And I did hear a few, but those were from people who had come all marching to applaud.

Lipstick Under My Burkha (with a kind of Azar Nafisi-ish title: arguably, the movie's biggest triumph) is about four women from four generations seeking emotional and physical fulfillment.

Belonging to the same neighbourhood in devout Bhopal, their lanes are flooded with repression.

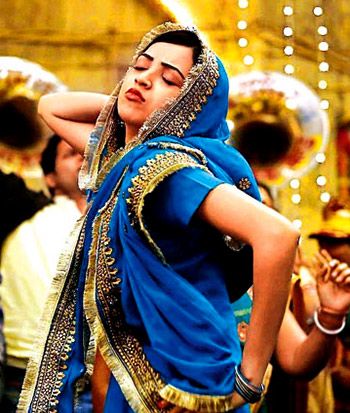

The principals are Rihana Abidi (Plabita Borthakur) -- innocently but rather prophetically named by her strict Muslim parents after a certain Barbadian singer -- who idolises Miley Cyrus, but who has to hide her worship of music, dance, and urbanity beneath a burkha.

Shireen (Konkona Sen Sharma) is a woman who knows how to dramatise a sales pitch, but who has been turned into a mere baby-popping machine by her always-tumescent husband.

Buaji (Ratna Pathak) is a widow with pride for her past, and fire in her loins that must be splashed over and calmed.

Leela (Aahana Kumra) is a beautician, who is marrying for her mother's sake, but who can only be tamed by a man she has pre-designated as her tamer.

This basic setting of Lipstick Under My Burkha has all the interweaving tensions of an Almodovar film (in festival circuit terms, the setting is pure gold) but Alankrita Shrivastava's characters just don't seem to have any life outside of the movie scenes they find themselves in.

The sad part is that for a huge section of our viewers, this is perfectly agreeable as long as the film picks on the worst prototypes we see around us: The worst husbands, the worst lovers, the worst chachas, the worst mithaiwallahs.

And the critics who review such films enthusiastically often reflect the same taste: 'At least, it's no Half Girlfriend,' they sigh.

Visually, the film has no lift; and neither does it successfully convey the everyday grit of its characters. Scenes are trimmed away just before they can hit their emotional peaks.

This is a film that exists only to 'make points' -- there are hardly any scenes of behaviour -- and it tries to move its audience at the most obvious places.

Produced by Prakash Jha, Lipstick Under My Burkha comes with some of his own chest-thumping sensibilities.

The actors are all given single note descriptions with no leeway to work out their characters -- you can see that they are clearly not bringing anything personal to their roles; there's an advertising campaign-like tone to all the performances.

Through expository dialogues, the characters reveal 'deep truths' to one another and to us.

When Leela and Shireen discuss their wretched existences, the film's basic finding bubbles forth: Women are constantly disappointed because they are constantly dreaming.

It's Buddha for the Beauties.

By the end, Shrivastava's four women have dined out on this theory and arrived at the realisation that maybe it's not the dreaming itself that's bad, but the *not dreaming right*. Now we are in Dale Carnegie territory.

The expositions are often intercut with readings from a sleaze novella whose refreshingly immoralist lead Rose is meant to be a soul sister to the four women.

For all its declarations of wildness, the breathy novella readings are perhaps the closest that Lipstick Under My Burkha comes to a felt expression of sensuality.

This is a film that trumpets out its sex -- it is content in being a girl's version of the archetypical boy's locker-room picture.

And if it was just that, that would have been fun too, but Lipstick Under My Burkha doesn't want to affect your senses, it wants to control your mind: It is a film that's constantly tiptoeing in its moral high-boots: An aggressively moral movie is what it is!

Shrivastava skimps on the men. And it's here that the triumph of a film like Hunterrr will become clearer to you. Harshavardhan Kulkarni's film was an unapologetic tale of a man's peach-chasing adventures, but all through those pursuits, we were also shown how the women felt -- we got their hurt, their distaste.

When Lipstick Under My Burkha has to do the same thing for its male characters, it croaks!

The film is programmatic, and you are never given an honest account of how the men feel when made to look small, stupid, and unwanted.

The repressive husband (Sushant Singh), the loverboy (Vikrant Massey), the stone-faced college stud (Shashank Arora) and Buaji's swimming instructor/phone-sex cohort (Jagat Singh Solanki), all go into a character-breaking spree when confronted with unsettling truths about their women.

The movie then becomes all false notes.

Especially problematic is the sequence where Shashank Arora's character backs away from the shop-stealer Rihana (that act just doesn't fit with the rest of his character); and neither does his sudden announcement of their relationship status on Facebook (that part is especially Prakash Jha).

It's when Rihana's shop-stealing tendencies are revealed and Arora backs away that a jealous classmate steps forward.

'Now do you understand how I became pregnant?' the classmate says with her chin thrusting out.

That line is as misplaced as the spirit of this movie and you will be compelled to ask, 'So how exactly did you get pregnant, young lady? Did Arora do it to you OR was it because you stole a pair of jeans?'

Humanity in art is when you allow each character her/his glory, but Lipstick Under My Burkha believes in heaping all its glories on its four women.

'If we can somehow lionise these four, maybe we can lay the groundwork for a better society,' the film seems to believe.

It's not that Alankrita Shrivastava is completely without talent, just that her talent is closer to novelists who write hard-edged smash books, books that maybe about lowlife and dark realities, but ones that have an unmistakable bestseller quality about them.

As a director, however, what Shrivastava doesn't possess is a talent for working with actors.

There is not one performance in the film of any underlying intelligence: It's all on the surface.

Ratna Pathak's Buaji will probably walk away with most of the accolades, but I don't think that's attributable to her performance necessarily.

The character has quite an effective sardonic flip-flopping design: On one hand she's guarding her feelings, and on the other hand, letting herself loose.

Pathak gets two or three of the best scenes in the film. One especially brilliant scene has her trying to recall her own name: She's been Buaji for so long that the name Usha is now a distant memory.

Shrivastava glides over that scene and the movie rises above its stodgy pointers and goes into the realm of tragicomedy.

In another smartly written scene, Pathak's Buaji tries to bait Konkona's Shireen with a 'No-Rent Month Scheme' just to stop her from telling anyone that she was out shopping for swimwear: That sequence is so desperate, it's hilarious!

Like Shireen's swimwear buying for Buaji, or Leela's dropping of Rihana at a discotheque on her motor scooter, the moments in Lipstick Under My Burkha that I liked best were simple everyday scenes where the women became magically available for each other.

Suddenly, the movie was a story of women, who know they are better than the men (better even than the life they are forced into) and whose rage has now turned into smirk.

I am sure a lot of the positive reviews this movie will receive will classify it as 'a much-needed conversation about this and that', but are these reviews forgetting what age we are living in?

Hello?

This is an age of small-town girls making Facebook posts about their bodily functions, of educational programmes openly discussing menstrual cycles, of television ads using the concept of women empowerment to sell ball-point pens.

What then is so courageous about a motion picture dipping into the same pool?

The strongest women that I have known won their battles by letting the men have the illusion of power and then doing what they thought was right.

Hanging around their kitchen area, these women discussed everything from world politics to black magic to the sexual inadequacies of their spouses (there was something spiritual about even their gossip sessions), the men just sat in the patio nibbling on their egos.

To these women, the mechanics of daily life presented so many opportunities for rebellion that they never felt the need for a grand stage or for hollow tokenisms.

Lipstick Under My Burkha touches, fleetingly, upon this aspect of female bonding that is removed from the compulsions of protesting.

When the film is not making points, it has some life.

When it goes off into conscious revolting, it's just distributing pamphlets.

© 2024 Rediff.com -

© 2024 Rediff.com -