'I personally consider Indian cinema as one of the most creative and powerful forms of cinematic expression in the world.'

'An average Indian film is 10 times better than a costly American production because of the creativity involved.'

Mainstream India cinema -- in Hindi and other languages -- has been popular with the Diaspora in the United States with many films breaking all time records. Salman Khan's Prem Ratan Dhan Payo had one of the biggest openings of a Bollywood film in the US. And then there are classic Indian films -- works of filmmakers like Satyajit Ray that have played successfully in art-house theatres and museums.

The recent restored prints of The Apu Trilogy ran for over three months at New York City's Film Forum theatre.

Now even museums are becoming interested in mainstream cinema. Earlier this summer the Museum of Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, New York City, played Mani Ratnam's trilogy of politics and love -- Roja, Bombay and Dil Se.

Last year the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York state, found a treasure trove -- over 700 recent commercial Indian films in various languages and over 6,000 film posters.

The films -- all in prints -- were lying in a warehouse in an old multiplex in California and were about to be destroyed. But the good people at the museum realised the cultural and historical significance of these films and stepped in to save them.

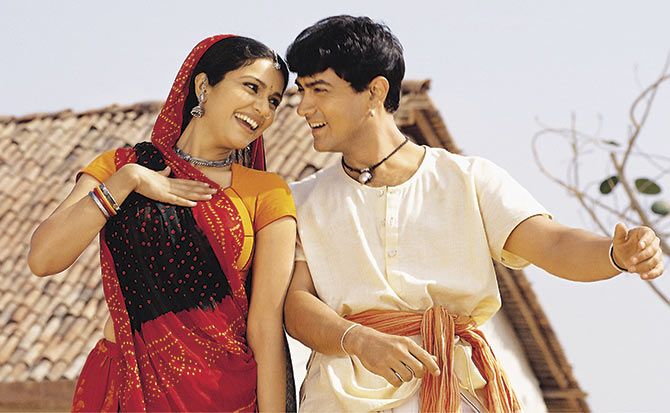

The museum now boasts of the largest collection of contemporary Indian films and they are just beginning to realise the value of the treasure they have acquired. The works include films like Devdas, Lagaan, Dil Se, Dev D and Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge as well as films in Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu.

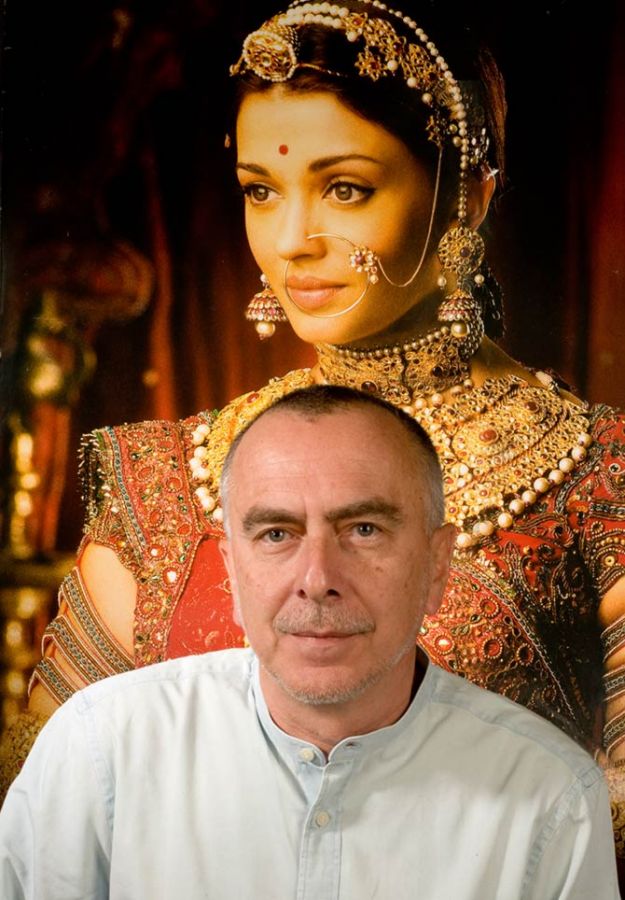

Aseem Chhabra spoke to Paolo Cherchi Usai, senior curator at the George Eastman Museum's Moving Image Department about the large donation and what it means to the institution's goals.

Cherchi Usai is a fan of all forms of Indian cinema and is thrilled about the prospect of using these prints to enhance the study of films from India.

Paolo, I read that there was a multiplex in California where the films were found. Where was it?

I think it was somewhere in Long Beach.

Okay, so it was in Southern California.

There was news that they were about to vacate the premises of a former multiplex that was dedicated to Indian cinema. They needed to empty the space immediately. There were films there and if someone had not picked up the films they were going to throw them in the landfill.

Didn't the distributors of the Indian films want their prints back?

Apparently not, because of it is extremely expensive to return the prints. Probably the distributors do not feel it is convenient to spend the money to do so. And besides, after the end of the commercial run of the film, when the film is out on DVD there is no incentive, because these films are dead as far as the commercial life is concerned.

With the digital age things are changing. Now you have DCP, which is only a digital file and a matter of sending a hard drive. The digital age has marked the end of the method of showing films on reels.

I work in a museum, and it is a non-profit institution that preserves the art of cinema. So when I heard there were prints that were about to be destroyed, I thought I cannot let this happen.

I personally consider Indian cinema as one of the most creative and powerful forms of cinematic expression in the world.

An average Indian film is 10 times better than a costly American production because of the creativity involved. So we came to the rescue.

How did you learn about the prints?

There is a community of film historians and museums, and we talk to each other all the time. My colleagues know that I have a special interest in Indian cinema. I got e-mails from more than one person.

I then sent a technician to California and we spoke to the owners and they said if you want the films you better take them now. They were willing to donate them.

When did this happen?

It happened in November and December of 2014. My colleague first hired one truck, but that was not big enough. So she rented two very big tractor-trailers, and with the help of some university students in California who were interested in the preservation of cinema, it took a week to upload all of this material. The owners made the official donation and the trucks came here in December.

If you acquired the films a year ago, why did the museum just announce the new acquisition?

Because we did not even know how many films we got. The films were just thrown around and not in any order. So we had a team that spent almost a year identifying all the reels. Often there was no identification.

I didn't want say 'Hey guys, we found a bunch of films.' I wanted to know the exact number and how many languages are represented in this collection.

So you have a catalogue of the films now?

Catalogue is a big word. We have a checklist. Now each print will have to be individually inspected. We have work cut out and I want to start work with the more important films -- the jewels in the crown. Actually, all the films are jewels in the crown.

You have checked the prints and the conditions are all good?

By and large, the conditions are much better than usual. I have acquired a few prints from India. These prints have had a long life, having been shown many times in urban and rural areas and they are not in great shape. The new prints we acquired are in much better shape.

Will these prints require some preservation work or are they going to be stored in the museum's vaults?

We have to work on the prints. In order to preserve a print properly it needs to be in a vault at 40 Fahrenheit, which is about 4 Celsius and 30 percent humidity. These are two important conditions and if they are met a film can last for hundreds of years.

It can be much more stable than digital. Which is why if a film was made on celluloid, museums prefer to preserve it in that form. It will last longer.

But maintaining a vault at that condition is a very expensive business. Then the prints have to be inspected, cleaned, the broken perforations have to be repaired. We have a staff of about 20 people who work on such projects.

This collection will take years to be preserved. It will take a while before we can make it available.

We have a collection of about 28,000 films in the museum. So this is a fantastic addition to the collection. But things do not happen overnight in museums. The important thing is that we have rescued these films.

For me this was an important event for another reason. For many years I have been trying to preserve Indian films distributed in the United States. It has always been very difficult to find places where the films are stored.

I knew that prints stay in the US, they are put in warehouses and not returned. But I could never figure where they are stored.

My mission has been of finding prints of Indian films that are sleeping in some warehouses in the US, because I want to save them all. And I know they are not just prints of Hindi films, but in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Punjabi and other languages.

Also I want the distributors to know that preserving a film is only a cultural mission. The copyright stays with the owner. But why let these prints die in a warehouse when they can be taken care of and then become objects of study for the community?

I am hoping through this donation we will be able to find more. My goal is to create a centre for the study of Indian cinema, where not only films, but also scripts, documents related to the history of Indian cinema are available to everyone.

Right now, what Indian films do you have?; Are they just classics?

Yes. classics. The first curator of our museum James Card was the first person in the United States to find a beautiful 35 mm print of the classic Indian film Chandralekha. We have the Tamil version, which was the first version.

Then we have the first version of Sant Tukaram. So I am not the first in the museum to care for Indian cinema.

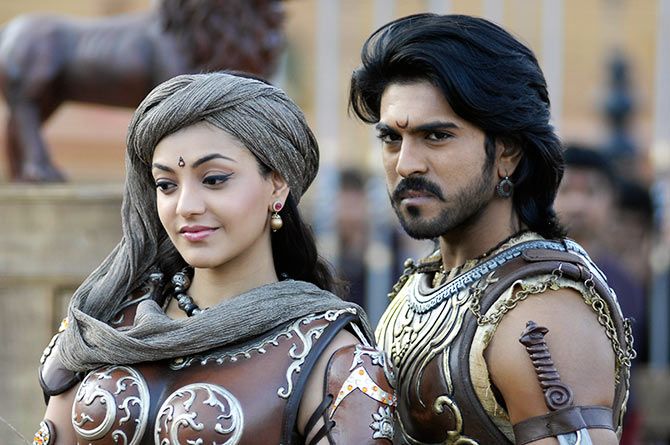

But recently thanks to the efforts of a colleague in India -- Shivendra Singh -- we have received a print of a relatively new film called Magadheera by S S Rajamouli (Eega and Bahubali). Now finally we have a much larger body of prints.

So now I can really think about the creation of what I want to call the Centre for Indian Cinema.

As a museum, besides preserving film, do you lend prints to other museums and theatres? Can research scholars come and see them?

It is both. People can come to our museum and study all the prints in our collection and we loan archival prints to other museums. The only condition is that obviously we are preserving the prints to keep them intact, so we loan them to museums that treat the prints like works of arts. We exchange prints with MoMA, UCLA, the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive, and other institutions.

It's interesting that most of these films are big grand commercial films, which are different from the films that Satyajit Ray was making and what museums usually collect.

There is a growing interest among museums and archives for contemporary Indian cinema in all its forms. We are not talking about the Satyajit Ray kind of cinema.

I find in contemporary Indian cinema, whether it is blockbuster or more independent production, there is quality in these films.

I am about to have a phone conversation with a colleague at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna and they have recently acquired prints of films by Mani Ratnam.

Things have changed in the museum world. Satyajit Ray is, of course, a giant of Indian cinema. But our perspective is now broader. It is not just about art movies. It is also about cultural history in a broader sense.

Even films that don't have any artistic pretence, they look great.

There is something about Indian filmmakers, even when they do something for purely commercial reasons, they have this gift, they know where to put the camera, they know how to edit the film, the sound design, the choreography.

I profoundly admire and respect Indian filmmakers. They make art, even when they are not thinking they are making art. This is what makes Indian cinema special.

I want my institution to become a place in the American continent where people can really appreciate this.

I am sure your museum has a large American collection, but do you also focus on other national cinemas?

Yes, we have a large collection of German, French, Italian films. We also have many British films. In a way, we have the whole history of world cinema here. Our collection goes from 1895 to the present time. It is a very international collection.

One of the first names of the museum was the International Museum of Photography and Film. They wanted to go beyond American film because cinema is the most international form of art.

So when I told our board of trustees of the new Indian collection, there was no discussion. They asked me if it was an important collection and I said 'Yes, it is.' And they said go ahead. We now have the largest collection of Indian films in the American continent.

And then you received a big collection of Indian film posters.

I forgot to mention approximately 6,000 film posters. We don't have the exact count. They were all rolled up. We also have a conservation department for photographs and posters. This will be a huge undertaking.

© 2025

© 2025