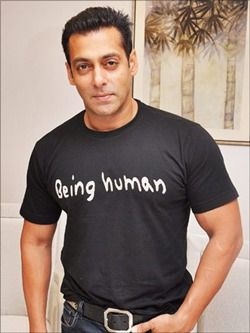

'Being Human is important to Salman. He makes it a point to sport the brand's products everywhere: on the sets, at events and even for court appearances.'

'It is a good public relations exercise. His lawyers will try to play the Being Human card to say he has changed.'

Is Being Human, Salman's apparel brand, an extension of his persona or is it a move to correct his bad-boy image, asks Ranjita Ganesan.

Salman Khan, Bollywood's most reliable star, is not an easy man to interview.

As a Business Standard journalist who met him in January just before the release of his film, Jai Ho, recalls, the actor behaved unpredictably, evaded questions and looked uninterested, even bored.

For about five minutes after walking in, he did not acknowledge her. Instead, he fetched food on a plate, played a few video clips of the film and halfheartedly answered her queries.

But when the reporter asked Salman about Being Human, his apparel brand that helps fund his philanthropic trust, he became focused, sat up straight in his chair and rattled off expansion plans.

"Whatever we do has to stick with the people. There is no scope for failure," the actor said.

Being Human is important to Salman.

"He lives and breathes the brand," says Kunal Mehta, vice-president of business development and marketing at Being Human Clothing, a division of garments company Mandhana Industries.

Every design in the brand's collections has to be approved by the actor, he adds. Salman makes it a point to sport Being Human products everywhere: on the sets, at events and even for court appearances.

Those who have worked with him claim that "Being Human and Salman are synonymous".

In fact, charity is now so much a part of his persona that when Jai Ho was slammed for its casting, jokes circulated on the social media that the film was "a philanthropic exercise to generate employment for a dozen retired actors".

The 48-year-old started Being Human: The Salman Khan Foundation in 2007. It works in the areas of education and healthcare. His inspiration is said to have come from watching his parents help the needy.

"Whenever they were approached for help, they would try and pitch in. More often than not, this meant financial assistance," says Alvira Agnihotri, Salman's sister and a trustee of the not-for-profit group.

"However, money in individual hands is prone to misuse; so Salman set up a foundation to contribute in a more structured manner." Typically, Salman charges Rs 30-40 crore for a film and a share in profits.

For brand endorsements, he gets about Rs 7 crore. The foundation was initially funded by Salman putting in his money, says Alvira.

To increase its reach and corpus, he started selling art and merchandise, the royalties from which go to the foundation. He next plans to set up cafes, gyms and a production house that will help raise money for the foundation. Salman was unavailable for comments for this report.

Mandhana Industries made and exported apparel for brands such as FCUK and Calvin Klein before it became the global licensee for Being Human.

Based on his appearance and somewhat nonchalant manner, the company's managing director, Manish Mandhana, could comfortably pass off as the fourth son of Salman's father, Salim Khan (one half of the legendary Bollywood writer duo Salim-Javed).

He met Salman's family some years ago through a friend and has been a regular at their home ever since.

In 2011, he approached them with the idea of starting a full-fledged apparel brand with the "beautiful name" of "Salman's charity", which is a spin on the term, human being. The royalties would go to the foundation, and Mandhana would get the opportunity to leverage Salman's popularity to expand business.

Salman's brand equity is not insignificant.

Never a thinking man's actor, he is loved by the masses. Unlike Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan, Salman is seen as un-scheming, unpretentious, uncomplicated and straightforward -- someone who has no time for diplomacy.

The Khan household is truly secular.

Salman, in fact, detests people trying to get close to him using religion as a pretext. These are all great attributes to infuse in a brand.

For a long time, Salman had the reputation of a brat, someone who always turned up late, was possessive about his girlfriends and would frequently fly off the handle.

It did not help when he was involved in two infamous cases: blackbuck poaching in Jodhpur and a hit-and-run in Mumbai.

Lately, however, his small acts of kindness have been heavily reported. For example, when he offered his paintings for charity or when he spotted a boy in a wheelchair and committed to sponsor his treatment. From a man-child, Salman is said to have become mature over the years.

Salman saw in Mandhana's offer a good opportunity to improve his charity's corpus.

Until then, all Being Human merchandise had been in the form of T-shirts stocked at the Cotton World chain, which reportedly gave Rs 100 from each sale to the foundation. Now, Mandhana gives 5 per cent from the brand's turnover to the trust, while online and retail partners contribute a smaller percentage.

The stark walls of Mandhana's office bear messages like "Be the change" alongside silhouettes of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King. The employees are young and busy: some work on designing graphic elements for the T-shirts, while others analyse patches of fabric.

Being Human reported net sales of about Rs 108 crore in its first full year of operation and is targeting Rs 140 crore next year.

The brand already accounts for 10 per cent of the 30-year-old Mandhana Industries' business.

It is sold at 200 retail points and six e-commerce partners in 16 countries. Plans are afoot to expand the offerings of apparel and accessories to include a wider range of skirts, shorts, chinos and flipflops.

The designs are at par with global fashion, says Saurabh Singh, head designer of menswear. He coordinates with four overseas designers who tour Europe to study trends.

Like Zara and H&M, Being Human follows a fast-fashion model, where the latest styles are taken straight from the ramp and collections are refreshed within weeks.

At the Being Human store in Ambience Mall, Gurgaon, a shop assistant signals that he is deaf and mute and points to the visual merchandiser, Rohit Dhiman. The brand employs at least one differently-abled person at all its stores.

According to Dhiman, the store gets a footfall of about 100 on weekdays and 150-170 on weekends.

The Salman phenomenon is hard to escape, especially since he is the face on most posters for the latest collection. There's a touch-panel which allows a user to swipe across the screen and see how an outfit would look on Salman -- menswear, of course.

Although the idea is to make charity fashionable ("look good and do good"), so far sales are mainly driven by Salman's popularity.

Just on Facebook, the actor has an army of 15 million fans who vociferously support and defend him. So, is his charity a good platform to promote his business?

"While charity definitely helps in adding a layer to the star's charisma, it is the brand Being Human that benefits from Salman's popularity even more," says Gautam Jain, head of insights (films) at Ormax Media, a media research and consulting company.

Mehta says the philanthropic aspect attracts more customers abroad, not in India.

However, Being Human's European distributor, Jean-Francois Caillet, differs: "In Europe, customers are wary about charity, so we do not stress on that."

Thus, he is pushing Being Human to mid-level and high-end boutiques, which, he hopes, will help it get recognition as a fashionable brand.

There are challenges ahead. The range starts at Rs 699 for a T-shirt, slightly higher than coveted brands like Zara. Raza Beig, CEO of Splash, a retail partner for Being Human in West Asia, says the basic 50 dirham (Rs 830) T-shirt is Being Human's best-selling product.

"If the entry-level price was brought down to 35 or 40 dirhams, they would make a killing," he says. Online partner Myntra counts it among the top brands with repeat-purchase value but its COO, Ganesh Subramanian, agrees with Beig about affordability.

The average Salman fan, after all, is not exactly well-heeled. As a result, Being Human is, as Mandhana says, "one of the most-faked brands around".

Its knock-offs abound at markets like Linking Road in Mumbai and Chandni Chowk in Delhi.

For the foundation, Being Human is just one of its many activities. It sees itself as an "NGO of NGOs" that identifies groups that are doing good work in the area of healthcare and education and helps them scale up by raising awareness or funds or both.

Salman's charity supports three secondary schools in Mumbai. It partnered with Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages to teach vocational skills and improve employability in non-urban areas.

On the health front, it helped prepare a bone marrow registry, held eye camps in rural Maharashtra and, in collaboration with Fortis Hospitals, agreed to fund the treatment of heart defects in 500 underprivileged children.

Last year, the Brand Trust Report named it the most-trusted NGO in India.

Salman's friends insist that his philanthropic side is "nothing new" and is certainly not for "the cameras or profit".

In the industry, he is called Salman Bhai (Brother), having routinely launched artists including composer Himesh Reshammiya and actress Sonakshi Sinha. Close friend and film personality Mahesh Manjrekar says that like his father, Salman has middle-class values.

"He hates luxuries. He is almost never inside his vanity van." Manjrekar discloses that Salman signs several cheques a day for people who come to him for help. Film writer Bhawana Somaaya points out that "he still lives in a small pad in the same building as his parents. If there is any emergency on the sets, he is the first one to reach into his pockets and pay".

Others are of the opinion that Salman stands to gain a lot from the philanthropic venture.

About a year ago, activist lawyer Abha Singh raised a petition for the actor's 2002 hit-and-run case to be fast-tracked, alleging that the police had helped to delay proceedings.

It led to the charges being revised from negligence to culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

"It is a good public relations exercise. His lawyers will try to play the Being Human card to say he has changed," she says.

According to branding expert Harish Bijoor, the concept gives Salman "the soft cues that he so desperately needs and makes him that much more human than a film star is perceived to be."

There are other issues as well.

"Salman is at the end of his career, and the target group of 15-30 will not see him as a heartthrob for long. The outcome of his court cases could also affect the brand's appeal," says Arvind Singhal, the chairman of retail consultancy Technopak Advisors.

That raises questions about its sustainability beyond Salman's popularity, a challenge the brand itself acknowledges.

"Salman believes that if a contribution to Being Human can be built into products of daily use such as clothing, it will help people make a contribution by the simple everyday act of wearing that clothing," says Alvira.

That is perhaps why Salman is thinking, talking and acting with urgency.

© 2025

© 2025