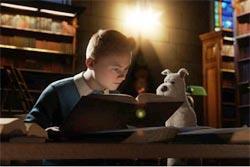

There is spectacular animation and some gorgeous staging but no heart and imagination in The Adventures of Tintin, writes Raja Sen.

There is spectacular animation and some gorgeous staging but no heart and imagination in The Adventures of Tintin, writes Raja Sen.There is a gorgeous moment in Steven Spielberg's Tintin -- and let us be clear from the very outset that Mr Spielberg's Tintin is an altogether different entity, not to be confused with Hergé's original -- where we see Hergé himself, Georges Remi, as a fairground caricaturist sketching out Spielberg's motion-captured young hero.

Behind the artist we see sketches of other characters he's drawn already, like Max and G, the Bird brothers. He finishes and shows off his picture -- a smiling Tintin, eyes bright and optimistic, head topped off by that tuft of carroty spikes -- and we turn back to the motion-captured version who raises a 3D eyebrow and calls the original 'not bad.'

Coming right after seductively beautiful opening credits in wonderful 2D, credits that race through the Tintin galleria with zippy panache, this feels evil. Things change after that hat-tip, and this is the moment we tell Snowy's Toto that we aren't in Herge's Kansas anymore. Tintin is now played by an actor, only not. He looks like Tintin, only he doesn't.

It is like watching lovingly made figurines prance around on a massive scale echoing the original, only not. It is like Tintin and Haddock forced into the shoes of Buzz and Woody, and directed by a blockbuster-churning committee. Michael Bay could have made this Secret Of The Unicorn, one of Spielberg's weakest films, an uninspired washout that bids goodbye to so much that made Herge's original one of the best books we ever read.

There is spectacular animation and some gorgeous staging, but heart and imagination, like the Bird brothers, have flown away.

Tintin taught me how to read.

My parents raised me on those fantastic comic book albums by Hergé (and obviously on Goscinny and Uderzo's Asterix) and, by three, I was beginning to pick out words based on the familiarity of panels I'd been read to from, over and over. Destination Moon was, I'm told, the book where the hieroglyphics of the English language began to unravel before my eyes.

It is, therefore, the greatest blasphemy to watch Secret Of The Unicorn being violated thus, with a Crab With The Golden Claws subplot forced in only because backstory-loving audiences might like to see how Tintin meets Captain Haddock. Aargh. Troglodytes, the lot of them. The fact that, in the books, Tintin only ever buys the Unicorn because he thinks it'd make a fine present for the Captain is no longer relevant. Forgive me for ranting like what you might call a nitpicking fanboy, but if there is one thing Hergé teaches us, it is the importance of detail.

Tintin's very appeal lies in the minutiae: in the perfectly rendered cars and planes; in the photorealistic use of perspective; in the rising hackles on a suddenly-awakened

Sure, there are bits that work, bits that come directly from those fabulous pages, but the rest of it is strictly pedestrian, an adventure sloppily pasted together with action setpieces to glue the film and keep it from falling apart. Good-looking explosions? Absolutely. Impressive chase sequences? You bet. But that's all filler in a depressingly vacant Tintin film that steers well clear of the spirit of the books. So clear, in fact, that it throws in maudlin, clichéd lines of clunky dialogue about belief and self-worth and one's true self. Ugh.

Visually, the filmmaker has tried to be very loyal to the source material, and often the frames look splendid (at least when you push those dismally dark 3D glasses out of the way to gaze at the vivid, mouthwatering palette) but it doesn't quite work for most characters. The joy of Haddock's face -- of drawing Haddock's face, anyway -- lies in the jaggedy edges of his beard, and here it appears dulled, to a realistic degree. What is the point of taking Hergé's glorious world and paring it down to look more like our own?

If I'd never read or loved or heard of Tintin before, I admittedly would not have been thus outraged (though I see no point in pretending to be ignorant or American) but even if Spielberg's film was called The Adventures Of JackJack, it would be a forgettable standard-issue action romp. A few colourful characters, some visually lush backdrops, some ha-ha gags. Nothing offensively bad, but nothing special. But it isn't called JackJack, and robbing Tintin of being special is as offensive as it gets.

I have Tintinophile friends who think the new film is an absolute hoot, but their enthusiasm is coloured purely by nostalgia. They aren't watching the film Spielberg made -- or hearing his unforgivably clownish Haddock speak -- but instead tripping through their own Tintin memories. Audiences without knowledge or fondness of the books, not caring as much, will swallow it like yet another summer release, just more Hollywood popcorn.

And in that lies my nightmare. That kids who haven't been exposed to Hergé's world will mistake Spielberg's Tintin for the real deal, and rate him several notches below Harry Potter or whoever it is they currently adore. It might be 'just a movie' but that is monstrous misinformation. Cruelty to children, even. Read the books, watch Stephen Bernesconi's 1991 The Adventures Of Tintin beautifully loyal television adaptation, available widely enough, and explore Tintin -- despite the film. That's what the real Tintin deserves.

To be precise, you deserve the real Tintin.

Rediff Rating:

© 2024 Rediff.com -

© 2024 Rediff.com -