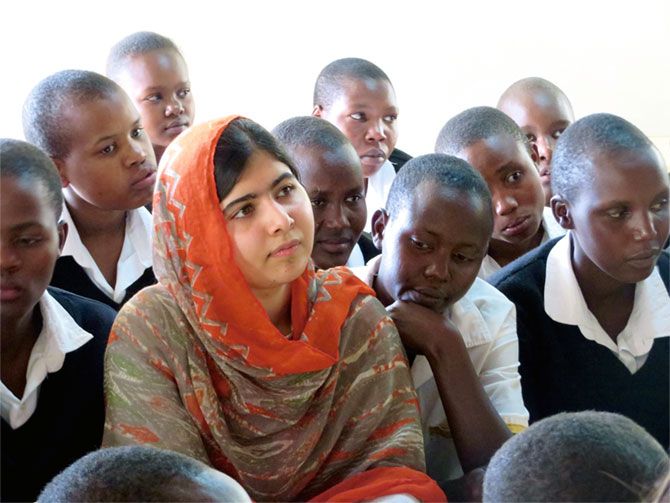

'She is a genuine, real, person who wants to be with girls who are suffering the way she suffered.'

The producers and director of He Named Me Malala speak to Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York.

Malala Yousafzai's story is so powerful and compelling that no fiction writer could have imagined it. She was shot by the Taliban at the age of 15, rushed to hospital and after months of medical treatment -- first in Pakistan and later in the UK -- she made a miraculous recovery.

That story itself -- coupled with her down-to-earth and inspiring speeches, support for girls' education around the world and the Nobel Peace Prize -- has made the 18 year old an iconic hero.

There was the best seller that she co-wrote with British journalist Christina Lamb, I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Fox Searchlight is now set to release a heartwarming documentary, He Named Me Malala.

The film is directed by Davis Guggenheim, whose previous works include the Oscar- winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth. The film's producers are Walter F Parkes and Laurie MacDonald who produced Gladiator and The Kite Runner.

He Named Me Malala looks at Malala's brief life from her childhood in the Swat Valley to the changes after she and her family moved to Birmingham in the UK. Some of the film's highlights include conversations with her father Ziauddin, brothers and her mother, who initially appears reluctant to appear before the camera. The film gives a sense of a tight family adjusting to its refugee status, while Malala has become a global figure.

Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com spoke to Guggenheim and producers Parkes and MacDonald before the New York City premiere of the film. He Named Me Malala opens October 2.

This is a story that the world knows, or we believe we know. It's rare that you get a story from that part of the world that really catches the imagination of the world, especially the Western world and even before Malala was honored with the Nobel Prize.

Was it a bigger challenge to bring this story to film?

Walter F Parkes: Laurie and I had the opportunity to read the proposal for the book. It was only 12 pages long. And yes, it is a story that the world knows, but even in the short proposal there were elements that we didn't know.

There were elements you would find in a good play or a good novel, starting with this idea that she was named by her father after a martyr in a war between Afghanistan and England.

The very first thing we talked with Davis was about the hidden thematic elements, that if we did our job correctly, we could bring to light in a way that news organisations couldn't.

Laurie MacDonald: There were elements about the Radio Mullah (a Taliban leader in Malala's village who would broadcast his messages on a loudspeaker) in the book proposal that we didn't know about. It's was very interesting that her story had classic elements.

The other important thing was that Davis wanted to get inside the family and present a more personal portrait that wasn't seen in the news or written in newspapers.

Parkes: It is very hard to see in the Western media the depiction of an Islamic family or person who is not somehow associated with terrorism.

When Davis and we met the family, we really enjoyed their company, to the extent that we wished that they were our neighbours.

In telling Malala's story we wanted to depict a real Islamic family that is not demonised the way it is so often done in the American media.

Davis Guggenheim: When you are making a movie about someone people think they know already, they bring with them baggage. I think I was that person. I knew her as a girl who was shot in her school bus. And that's not who she is.

Characters are defined by the choices they make. And Malala made a choice to speak out and her father made the choice to let her speak.

To my mind she is not a hero because she was shot in the school bus. That is the opposite of how you should know her.

You should know her as a courageous girl who thought her voice mattered and she spoke out.

There have been many humanitarian heroes who have become celebrities and they also become brands. Malala has been a brand for a while.

How do you tell the story with integrity knowing that there is a Hollywood machine protecting the image, the brand, even though there are great moments in the film when she is just a girl?

Guggenheim: My process of making movies is to get to know the people and reveal them in the way I see them.

MacDonald: Malala and her family, they don't have much support (then). When we were making the movie they were just this family who had moved to Birmingham as refugees. They knew no one who was advising them. Perhaps the book editor became somewhat of an advisor.

Even though she was so well known, we did not see any handlers around them.

Parkes: If there is any Hollywood connection. it is when Fox Searchlight came in very late into the process.

I know her story is very compelling and it is all true, but I wonder how she became what she has become.

You said there were no handlers there, but why is it that it seems she is manufactured by a PR machine?

Parkes: There was a moment during my second meeting with the family and she was about to deliver the UN speech. Her dad asked me if I wanted to hear her UN speech. And she like any teenager said, 'No dad.'

He insisted and she came down with two pieces of printed paper. I heard her say the 'One teacher, one student, one book...' speech. I was so surprised and I said this is beautiful.

She is a real deal. And it stunned all of us, because we do this all the time about movie stars and inevitably we are disappointed.

Then you meet Malala and you find a girl who not only fulfills the expectations of the myth, but she is sort of even more human than we imagined. She cares about her school work more than anything else.

Guggenheim: When I was with her in Jordan at the Syrian border, no one knew who she was. She was just a girl in Jordan. Her 18th birthday was coming up and I said you are done with your exams, you have a week off, what do you want to do.

She goes to Jordan to be with the girls. It wasn't a huge press thing, but she felt connected to the girls.

She is a genuine, real, person who wants to be with girls who are suffering the way she suffered. Just because people want to write stories about her doesn't mean you should draw those conclusions.

Parkes: And by the way she is the first one to say, 'I am just a girl, but also one of the millions of girls.'

The fact is that we are story driven people, so if there is a vivid story like this, we will grab on to it. I think it is unfair that there are many other stories and many other girls who have given up so much in favour of trying to get an education.

Do those stories get the light shone on them? No!

Through the film we are hoping to shine the light on the wider reality.

MacDonald: With all the celebrity talk, it is important to note something we forget -- that she is a very regular girl who deeply misses her home. That was a beautiful life. She had a deep connection to places she can't go back to.

Guggenheim: They were an ordinary family in the Swat Valley, and something very precious was taken away from them.

Telling their story was part of survival, part of bringing help. When they agreed to the BBC blog, or The New York Times video, that was part of their mission.

In our world, through our lens, PR machine means you are going to get something out of it. We are in a selfie-driven culture, where people are ensuring their own narrative, because it is promotional.

If you knew them, you would know that's not what they do.

MacDonald: No one imagined that the Taliban would shoot a child of her age. They really didn't believe it. Internationally it was such a shocking story.

There are many compelling stories, but she was 15 years old. I do think there is something about her age when she was shot that speaks to everyone. And the miracle of not only surviving, but also becoming stronger and fearless. She still takes risks by being out there.

How much was Malala and the family involved in the tone of the film?

Parkes: Davis is a very experienced filmmaker. He spends hours with these people, not filming, but just talking.

What you are seeing is the product of over 20 interviews and 100 shooting days. So the family had to give into the process.

Guggenheim: The only substantial note they gave us was about how Islam is projected. They were smart notes, because we are people from the West. And we incorporated them because it only made the movie better and more nuanced.

There are a lot of documentarians who have an oppositional approach -- I am going to turn my camera and chase you as much as I can and you are going to hide as much as you. I am the opposite.

I say let's tell the story together. What you hear in the movie, it feels like narration, but it isn't. It is they telling their own story. And that's why it feels very intimate.

Was there anything that you wanted to include that you couldn't?

Parkes: I was just thinking about the sequence where we talked to her about what she wanted to be when she grew up. It's not in there, because the hardest thing about documentaries is creating a structure.

Cutting documentaries is like writing. There are many beautiful moments that are powerful on their own, but were hard to fit in the film.

Guggenheim: First, she says she wanted to be a mechanic, then a scientist, and an actress. It was a lovely scene, the dreams of a girl.

MacDonald: It was all animated in a whimsical way.

Can you talk about the use of animation in the film?

Guggeheim: Part of my process was to sit with an audio recorder and just talk with Malala and out of those conversations came things like ‘I wanted to be a mechanic. These are very personal things -- a lot of them have no place in the movie, but were capturing the spirit, the romantic memory of living in a paradise like the Swat Valley.

To capture that, we built a little animation company in my office to do the Battle of Maiwand (where the Afghan hero girl Malala died on a mountain top), but we wanted to do it from the mind of a girl who has her eyes closed before she goes to sleep, how she would imagine being named after this brave girl. That became the spirit of the animation.

Can you tell me about the family? How are they adjusting to the new life, especially the mother? The boys are young, but the mother's story in the film is fascinating.

Guggenheim: This question comes up lot, because Malala, her father and brothers are in the foreground, and the mother Tor Pekai Yousafzai is often in the background. And people read a lot into it.

The truth is that Pashtun culture says being on camera is immodest. And she made the choice and I was respectful of the choice.

Parkes: We showed them a cut last year. They were very articulate. Of course, Malala was taking down notes. At that point, Tor Pekai didn't want to step forward and didn't feel comfortable talking.

We went to Birmingham again and suddenly the kids were talking and something miraculous happened. Tor Pekai whispered something to Malala who then said, 'She wants to be in it.'

It's important to remember that the language was a barrier for her. She's a Pashtun speaker. So it is not even Urdu.

MacDonald: I am not sure if you have read the book, but quietly there is not a decision made in that house without her opinion. I think Zia relies a lot on her. She's very intelligent and has a great judgment.

A lot of Malala is Tor Pekai. And when we speak about how tough it is for the family, she was such a part of the village, its culture and neighbours.

Who is the audience that you aimed the film at?

Guggenheim: I think a lot about my audience. When I made An Inconvenient Truth, I made it for my Republican cousins in Ohio. They are very nice people, but they are Republicans. I wanted to convince reasonable people. I didn't want to make a heavy-handed righteous film.

In this movie I had my daughter in mind. She is 14. I didn't want it too heavy and into the geopolitics of the region. I wanted my daughter to think that if push came to shove, she would raise her voice and speak out.

How has making the film changed your life?

Parkes: I am not sure if it changed my life or confirmed something one tries to commit to and often doesn't do.

When we make movies, we take the Hippocratic Oath -- which is, we don't make movies to make the world a better place, we certainly try to do no harm. But every now and then you can try to authentically tell a story that can actually do something for the world.

And I think making this film, having the opportunity to know these people and understanding Islam better and seeing the response, it was so enriching. It pushed me more to an active sense -- you know you can do better than just do no harm.

Guggenheim: I am sitting at my kitchen table with my son and my two daughters and I read something in the paper and I ask him, 'Hey Moss, did you see this?' I look at my daughter and she is saying, 'Why didn't you ask me?'

This man -- Zia -- has challenged the way I am a father in a fundamental way. There are some simple truths that come out of this film -- schools and liberation, girls are equal to boys that we forget.

I can say my daughters are equal, but may not have always acted on it. Zia not only says he believes it, he acts on it.

MacDonald: Clearly beyond how remarkable her story is, hopefully the audience realises how many potential young woman are out there who aren't getting educated. They could be brilliant and could bring so much to the world, but they don't have the access.

The movie does present her ordinariness and it's so intact.

© 2025

© 2025