Director Matt Brown tells Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com what it was about The Man Who Knew Infinity that made him persevere for a decade to turn the book into a film.

Filmmaking can be an extremely difficult and complex process, and for every film that gets made, there are scores of good scripts that are ignored. But some filmmakers are persistent.

Matt Brown spent 10 years trying to get a film based on the life of mathematics genius Srinivasa Ramanujan made.

Brown, whose only other film credit was the romantic comedy Ropewalk (2000), was convinced a film based on Robert Kanigel’s book The Man Who Knew Infinity had to be made and Ramanujan’s story had to reach the world.

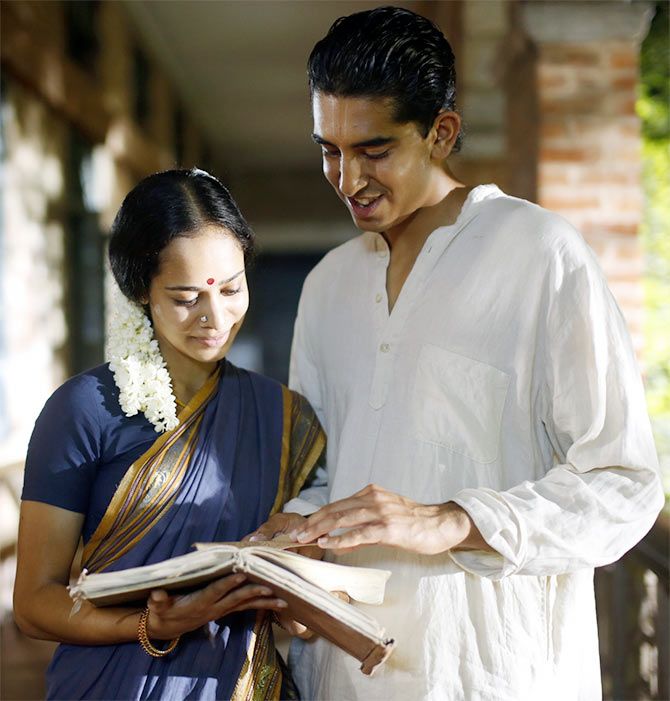

His persistence paid off when he got the box office-worthy name of Dev Patel (post the success of the Best Exotic Marigold Hotel films) to play Ramanujan, and Oscar winner Jeremy Irons to play his mentor G H Hardy.

Brown tells Aseem Chhabra/ Rediff.com about the making of the film.

Can you address the issue that it took you so long to get this film made?

Well, it took a decade to get this film made.

I guess it was about two years ago when I met with Dev, and he read the script, loved it and we began tweaking it a bit. And we took it to Jeremy. Ed Pressman (producer of The Man Who Knew Infinity and films such as Wall Street and American Psycho) had worked with Jeremy on Reversal Of Fortune.

Dev came on board before Jeremy?

In this recent incarnation, he did. We have been through many incarnations of this film.

Were there other Indian actors you considered?

There were at different times. It was all about how the financing was going to work out of India or here and who the people would allow you to make the movie with.

At one point, I got so fed up I said I am done. I felt that after seven or eight years I had that right. By then Dev had grown up, and he was of the right age (Patel is 24 while Ramanujan was 32 when he died).

I said I want the script to be sent to him. We hit it off. He’s an amazingly instinctual actor. He’s so smart and instinctual in terms of the script too, which was a pleasant surprise.

Why did the financing take so long?

I would say the film is about an Indian mathematician at the turn of the century, with no major love interest at Trinity in England.

I was asked at one point to have a love affair between him and a white nurse. And the film would have been financed.

You lived with the project for so long. What drew you to the story, also knowing that it was such a difficult project to sell?

I knew that. It became personally important to me.

I had read a book called Birdsong; it was about the Great War. I was fascinated by it.

Then Tristine Skyler (executive producer) gave me the book The Man Who Knew Infinity and that was also set during the Great War. I started reading this incredible story between these two men and the journey.

At that time, I was personally taking care of an extremely close person in my life who was going through cancer treatment... The themes of isolation that Ramanujan also felt while he was sick and going through all that, directly spoke to me at that time. I wrote the script in the oncology ward.

That was the initial chord. But then as you get older, years go by, things change and you still cannot make the movie. The person I was taking care of got better and I became a happier person. And he actually ended up doing the score for the film.

Some projects you have for very long and they fall away and some just grow with you. This one grew with me and it became about the cost that comes when people wait out of fear to connect and their relationships. That became important to me. As a person, I was really interested in it deeply.

As far as knowing how difficult it was to make the film, yes I did know. I made a tiny little movie 14 years ago that I didn’t get to finish -- it was a crazy situation. I suppose I was nervous about directing again, so subconsciously I picked the most difficult subject in the history of the world to get made.

How do you make a film about something as complicated as mathematics, and it looks so easy and approachable on the screen?

I think what they are doing -- they are artists. That’s what I was trying to get across. How much I succeeded, we’ll see about that.

I like the idea that pure mathematicians are artists. It’s tragic that J E Littlewood, a pacifist, had to join the war and use his art to create ballistics. That was the thing of the time. They wanted to use the mathematicians to create a more effective war.

If you could view them as artists, you could understand their passion for the work they did. I thought this could be accessible to all viewers. It’s not like you look at a Man Ray or a Picasso and actually see a painting, better than you can see numbers. And you have to have the emotional relationships to connect the audience with the mathematicians.

There were a lot of things I’d have loved to have done visually, but we didn’t have the budget or time to do. But I didn’t want to have floating dancing numbers in the sky.

What does it take to create a period piece? I know Cambridge University still looks the same, but India has changed.

When we were in Chennai at Presidency College, we went to a library there. They hadn’t moved the desks or papers in a 100 years. Everything was in its original form. And the funny thing is they were going to throw it all out about a month later and replace them with ugly plastic desks.

Our production designer Luciana Arrighi literally chained herself to the door and said you are not coming in here until after the shoot. We couldn’t afford all that furniture. It was incredible.

It was a very difficult to shoot in India and recreate for the period. We were looking for an authentic street of Brahmin houses and that was almost impossible. So, we ended up going to Kumbakonam which is where Ramanujan grew up. That was strange.

We had to drive down six hours on one of the most harrowing roads you would drive on in your life to get to a location that would look like a street in 1914 Madras.

You shot some scenes inside a temple with a long corridor. Where was that?

A private temple in Kumbakonam.

So, what were the main locations in India and in England?

We shot in Chennai around Presidency College and in Pondicherry for a few days and in Kumbakonam for a couple of days.

In England, we shot in Trinity College. That was the first time a film was allowed to be shot at Trinity. They opened the gates for us. They read the script and they embraced wanting to tell the story.

We ended up also shooting at Oxford. The script says we were in the Wren Library at Trinity, but instead we shot the interiors at Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Well, the Hogwarts Library scenes were also shot at the Bodleian.

There you go. We went to Hogwarts.

What was the most difficult thing to shoot?

I can’t say it was easy to shoot in Chennai with fireworks going up every minute.

Fireworks?

Saturday night in Chennai is a big wedding night. It was incredible.

When you have an actor like Dev Patel, who is still young, although he has worked quite a bit, and someone as seasoned as Jeremy Irons, how do you create the ambience on the set that they are equal? How did you work with them separately and together?

They are very different actors and very respectful actors to the craft of acting and to the director. So there was a lot of respect -- even for the material and the story they were telling. There was a lot at stake for us to make this film. It was incredibly important for Dev and also Jeremy.

They came prepared and we worked hard before we got there. And everybody checked their ego at the door. It was education for me in a way I have never thought it would be.

Jeremy was a mentor to me throughout the shoot in terms of his wealth of knowledge. He worked so hard and it is a different Jeremy Irons you see. He let down his guard.

What do you expect people to take from the film?

I hope if people are moved by the film they might turn to the person next to them and engage in their relationships. That would be wonderful.

To have a person like Ramanujan with no education to speak of and doing the most advanced mathematics the world had ever seen, it’s incredible. He wrote three letters to three different professors and two of them flat out rejected him. Being the kind of person he was, Hardy took a chance on him. That was a miracle.

There are a lot of Ramanujans out there and it will be wonderful if this film -- I am probably wishful thinking here -- could make people appreciate that geniuses are artists and take chances on them, giving them opportunities.

I have been working closely with Manjul Bhargava (winner of the 2014 Fields Medal, the India Abroad Publisher’s Special Award for Excellence 2014 and India Abroad Face of the Future 2008) who came on board as an associate producer. We have been trying to find a way to set up a Ramanujan scholarship fund throughout India.