Quentin Tarantino, declares Sreehari Nair, will be remembered as someone who made just two great movies, and who then brought misery upon himself.

Twenty five years ago, when Uma Thurman, in bowl cut, cropped pants, and gold slippers, and sucking on a cherry, explained to John Travolta, why 'comfortably enjoying the silence' matters, a roar went up inside many of us.

Now, Quentin Tarantino has brought out Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, a film filled with Uncomfortable Nothings -- and fans of the writer-director, upset by the dryness generated in their throats, have been consoling themselves (while seemingly consoling others) with: 'Oh, it's a Hangout Movie.'

On the surface, this rationalisation may seem harmless.

It's just that Hangout Movies (the good ones, in any case) are never so sparse in details.

The Nothing Happens Rule -- which works wonderfully when slapped over such titles as Rio Bravo, Dazed & Confused, and The Big Lebowski -- is a nudge at the audience, imploring them to look beyond the plot.

The problem with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is that looking beyond the threadbare plot, one only arrives at wide and empty streets, dull boulevards (couldn't they get someone to water the lilies?), close-ups of shoes (and of course, feet!) and film sets, big enough to host raucous political conventions but occupied here by a handful of characters, not one of whom has any real personality or bounce.

There are scenes after scenes, and uncut shots after uncut shots, with practically nothing to see, hear, or savour. (Unless you count Tarantino's patchy recreations of 1960s' radio tidbits as honourable efforts at building aural density).

My guess is, Quentin Tarantino, 50 years from now, would be remembered as someone who made two great movies (Jackie Brown being his finest hour), and who then brought misery upon himself, doing meditations on the Spaghetti Westerns he had grown up admiring.

Here again, Tarantino situates his story in the Hollywood of the late 1960s but ends up making out of it a standard, airless Western.

Meaning, he fails to tap into the sly poetry of this unique Hollywood age which had vibrancy and death, big studio posh and an emerging love for squalor, living side by side.

Tarantino's Hollywood -- imitating the 'bad things are about to happen' spirit of Westerns -- appears to know already that it will die; and worse, it appears to have given up.

Presumably in anticipation of the apocalypse, the actors (except for Margaret Qualley, who briefly brings the movie alive) take on faces that look rigidified by design. Not even three full minutes of being windblown and neon-dusted seems to corporealize these stony faces.

It's in his use of actors that Tarantino's odd approach to crafting this picture becomes most evident. As a viewer, you aren't treated to strands of behaviour: just attempts at going for the Big Numbers that keep running into Logjams.

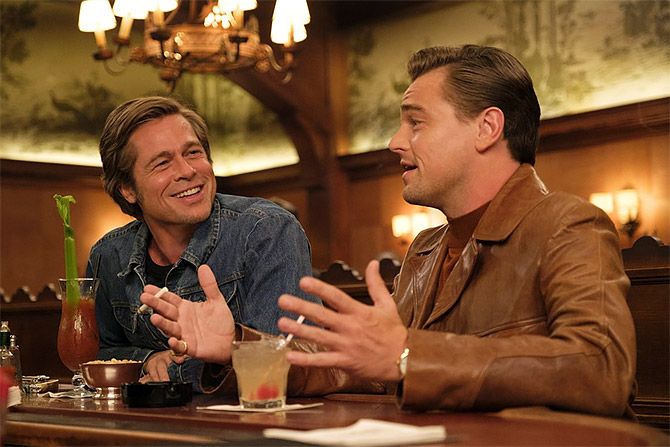

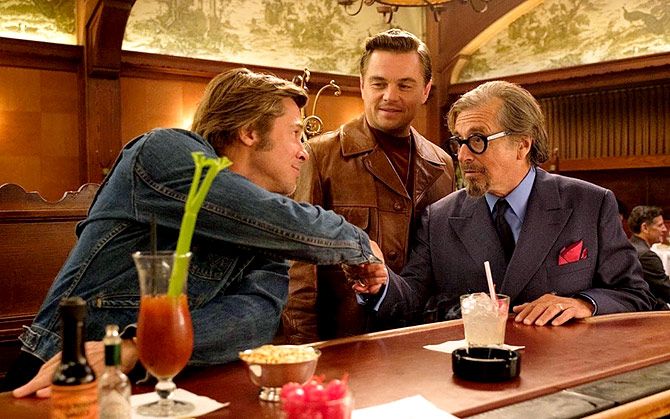

Leonardo Dicaprio's Rick Dalton, a waning star of old Westerns, has a face that threatens to finish up in a permanent shrivel.

The Hotshot-To-Shrivel arc is a romantic template, like, say, the Drunkard Philosopher or the Artist-Bum; and every time Dicaprio chokes on his misgivings, performs self-flagellation, or sniffles before delivering a line, we are supposed to marvel at the actor’s courage in baring himself, as we are watching.

In contrast to Dicaprio, Tarantino sets up Brad Pitt's Cliff Booth -- Dalton's stunt double -- as a Man with a Code. He's the hero in possession of the loaded gun; and he's a hero because he has the good sense to never fire the first bullet.

Conceptually, Booth is the most interesting character -- and it's a shame that the movie';s only demand from Pitt is to assume a dopey face with just that hint of 'I want to break loose.'

Then there's Al Pacino and Nicholas Hammond looking and sounding like boneheads talking cinema.

Kurt Russell, from the first time he shows up, till he exits, gives you the impression that he'll now go into a snit -- an ideal that Zoë Bell, giving a gratuitous performance as Russell's wife, achieves in a matter of a few frames.

I could guess the tone Tarantino wanted to hit with this one: more like a Comic Memorial to Sharon Tate -- funny, when we expect it to be sad; and wistful about those things that we might otherwise toss away with a laugh or two.

But there's no unifying energy in the movie for that tone to materialize; and at places, it becomes obvious, that the shallowly entertaining director has gotten himself entangled in material he has no real feeling for.

In making a comic memorial, Margot Robbie's Tate character is allowed to be nothing more than a Memorial. And when she sits in a movie theatre, soaking in the cheers of the audience, Tarantino seems to be begging us to light candles in front of her face.

We might as well do that because nothing is coming by way of Robert Richardson's artificially lighted atmosphere, where the days are unbearably sunshiny and the nights, satanically dark.

Tarantino's first three movies, by far his best, were shot by Non-Americans, and I am convinced now, that part of their vaporous power came from the fact that the worlds he had envisioned back then, were, eventually, anointed by foreign gaze.

The whacky unpredictability of the violence, the poeticizing of cheapness, the romantic treatment of the gangster, the outlaws, the fallen angel... there's some strange tenderness we felt in the way Andrzej Sekuła and Guillermo Navarro glanced at the familiar elements and themes of hardboiled American cinema.

You only have to compare the airport scenes in Jackie Brown or the diner scenes in Pulp Fiction, with similar ones in this film -- here, they just don't play. And that's in part because Robert Richardson's compositions and his capturing of décor bear no sense of wonder.

Richardson's eyes may not be sufficiently moist to give us that lift, but Tarantino's writing, truth be told, doesn't offer much of a foundation.

You might have thought about it or maybe not, but the desire to reproduce the scale of the archetypal Western, complete with its open spaces and all-consuming air, has been slowly eating away at Quentin Tarantino's one true gift: Dialogues.

His lines have, since Kill Bill, tended to be all banter, coming out of nowhere, and with some pop-psychology mumbo jumbo thrown in for good measure.

As the commonly leveled accusation goes, to be a half-decent Tarantino character, one has to be talkative and compete orally with other Tarantino characters on the parameters of pop culture knowledge, historical gossip, and of course, range of vocabulary.

Ask yourself: why was Jamie Foxx's Django such a twerp? Because he didn't open his mouth as much as the usual Tarantino people.

This time, T willfully cuts down on the colourful dialogues and reaches out for Inner Life.

And I kept wishing he hadn't done that because in attempting to make his characters sound like characters, all he serves up is one banality placed atop another.

The lines in OUATIH are low-key, listless, hushed, and they blur out on you.

The repetitions in the dialogues come off like bad parodies of Hemingway -- they don’t build on anything, or build into anything.

A taciturn Tarantino character, I now surmise, is someone who doesn't leave the page and announce himself.

Here, there are about two dozen such starving spirits, Roman Polanski included, holding out their bowls, beseeching their creator to give them some words.

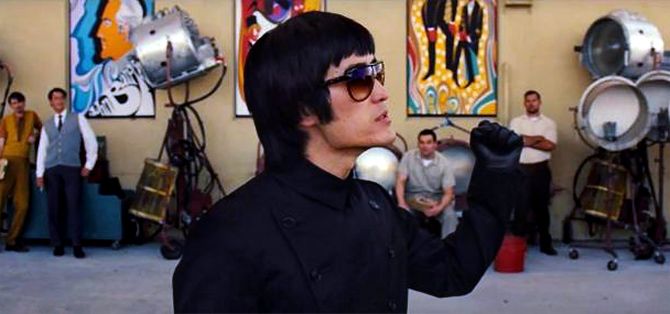

The big casualty of this deliberate withering away of style is the Bruce Lee sequence.

Now here was a sequence that called for that characteristic Tarantinoesque overflow, verbal hyperactivity, voracious onrush, and those grand bows to popular culture.

This time, however, the writer of such charms as 'What does it feel like to kill a man?' seems not properly lubricated for the occasion.

So Mike Moh's Bruce Lee neither leaps nor stays grounded, he is kind of bowlegged and graceless, saying nothing of any particular interest, just drawling away, merely setting the stage for the otherwise dopey Cliff Booth to come snip his tail.

The Bruce Lee sequence is what left me speculating if Tarantino had, during the making of this picture, perhaps, witnessed the coming true of his biggest fear: Of turning into an Old Man Film-maker.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is an old man movie. Its tragedy is that its maker is an old man who is not worldly enough.

A film-maker who has discovered multitudes within himself, who is genuinely interested in human beings, who is perceptive about human nature, and about the true nature of Evil, such a filmmaker can direct a great film even from his deathbed -- as John Huston, speaking through an oxygen mask, had demonstrated.

Tarantino's sweet spot (as he'd once described) was European Arthouse meets Blaxploitation -- and it was in how he allowed the subtexts to freely crisscross, how he allowed Camp and Heartfelt to exchange clothes, in the wonderful tricks he played with the narrative in his green years, that he managed to tickle areas of our body we didn't even know were receptive to tickling.

A nimble, airy film-maker, whose exuberance gets mistaken for depth, is, in essence, a film-maker who is denied the opportunity to develop as an artist.

Tarantino, very early on in his career, got slotted as a more important artist than what he actually was. Meaning, he was thereafter absolved from the responsibility of both looking inward and expanding outward.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood lacks the buoyancy of vintage Tarantino, sure.

It also seems made by a man who hasn't been stepping out of his mansion for years now, except to attend friendly parties.

This is why, we see in the film, a lot of set-pieces, but nothing much to fill them with: No characters with free will; no real air of excitement; no splendor in the build-ups; no tension in the small events -- hell, even the gossip is flat.

I would have taken an ambitious failure; but this is a beast, flabby in all the wrong places, just dragging its weight around.

And while the same description would fit Quentin Tarantino perfectly well, fans of the onetime-whiz kid, being not much brighter than fans of Marvel pictures, have found ways to rationalise his newest mediocrity.

I read an online discussion about how cleverly Tarantino has introduced Bruce Dern's George Spahn character into the story. The point that never got discussed was how insipidly that whole scene is mounted.

This is the same kind of blindness-in-the-face-of-supposed-auteurism that made one overlook the psychological howlers in Inglorious Basterds, the grand editing gaffes in Django Unchained and the pointless logorrhea of The Hateful Eight.

Though some confusion about his divinity has begun to stir, both the Cinema God and his Devotees are positive about one aspect: Those jolly rewritings of history, which some even seem to take as representing Tarantino's Humanity.

I don't know what is left of this brand of humanity, but here's the closing anthem of its latest chapter: 'Oh, how well He fried those hippies, our Father from Hollywood Heaven.'

What is interesting about the Quentin Tarantino Conundrum is that it mirrors the big problem with American movies of the last 20 years: They haven't been speaking to what is happening in the country, in a way that many of the best movies of, say, the 1970s did.

There was a time when America's finest novelists, Mailer, Bellow, Roth, saw American Movie Directors as counterparts, in their dissection of the American Character, and in their subtle confronting of the paradoxes in the American Dream.

It is American Television that is performing this cultural duty now.

And when you look to American Cinema, all you get are high-minded message pictures or some kidding around with established film genres.

There is a strain of doziness that shines through when Indian film critics talk up this crop of flaccid American movies, while trashing the worst that Bollywood has to offer.

I can only speak for myself here, but the best of Indian regional cinema today are setting off the kind of sparks in me that very few from the current lot of American movies have been able to match.

Trends in art are known to be cyclic; and so, perhaps, things would rally for Hollywood, too.

But how the season has changed for Quentin Tarantino!

From writing a spec script which got Harvey Keitel so excited that he declared 'the writer of these words, unless he is a complete idiot, must be given a chance to direct this picture,' TO, writing a script like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which if it weren't for the name on its cover wouldn't have made it past the lowest executive in a film company.

The only time I felt any connection with this minorest major motion picture was when it allowed me a chance to see the parallels between its lead character and its creator.

Tarantino outlines Rick Dalton as a Has-Been, who is struggling to regain lost ground.

I guess it's fair to say that while some artists get turned into Has-Beens by outright failures. For others, it is undeserved success that does the trick.