'Are we too close as well-off Indians, all with servants and drivers and tuition teachers ourselves, to be able to understand why it is all so awful?', asks Aakar Patel.

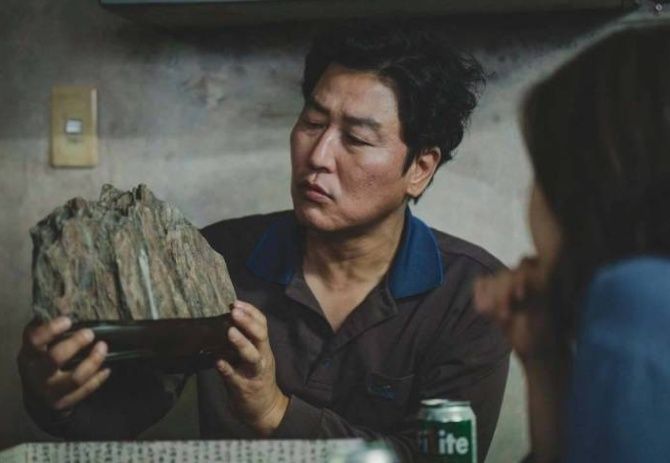

I saw the movie Parasite and couldn't understand why such a big deal has been made of it.

The film won four Oscars a few days ago, including Best Picture (the first foreign film to get the honour), Best Director and Best Screenplay.

The Oscars are often like Nobel Peace prizes. Not given to Gandhi, given to Henry Kissinger and, therefore, perhaps not the best judge of quality.

But there would have been some strong appeal towards the movie from the film set, because it made a lot of money at the box office and also broke the language barrier for best film at the Academy.

I tried to figure out what that powerful appeal in the film could be. The story is fairly simple.

A poor family in South Korea inveigles its way into a rich one's home. One of them, a young man, becomes a tutor, his sister the art teacher, the father the driver and the mother the housekeeper, all without the rich family knowing that they are related.

They do this to no particular end other than to keep the job (they aren't planning on stealing or murdering or anything) so perhaps such jobs are not easy to find in that society.

But the family approaches it with such intelligence and quick thinking that one wonders why they aren't employable, and why they remain in poverty.

The son is sharp and focused. The daughter is absolutely brilliant. She tames a wayward child and convinces an elite family that she understands and can teach art at a deep level.

The father is apparently a flawless driver, in the eyes of the man who has hired him and who is chauffeured around in a large Mercedes saloon, not an easy car to master.

The point is that these people all have some talent, determination and drive. What stops them from doing well in their society? This we are not told by the plot or by the things that surround us in the movie.

They live in a slum-like space (I use the awkward phrase because we Indians are familiar with a certain type of slum, which this is not) and are able to effortlessly make the transition to a couple of rungs above. How?

Are they very well educated and exposed in a system that provides the basics of health and education but is unable to provide employment?

What held them back from finding success or a middle-class existence?

Are these things that held them back visible (meaning in terms of the way that they look or speak)?

Or are they invisible? That is a question that those of us who come from deprived societies will think about.

I could not get the answers to any of these from the movie. And so for me the cause of the primary conflict in this class war and the point of tension remained vague and undefined.

After the movie, I told my wife I didn't think much of it. She said she liked it, and when I asked her why, she said: "It's a modern theme, about inequality, which is important to address. There are few deep-plot films these days. Most of what we get is war films, half the releases are Marvel and Wakanda and that kind of thing."

She said the movie was also aesthetically pleasing: "The house, the food is stylised. It's not a perfect film, but it's definitely a good film."

She added that getting an Oscar is not the movie's high point. All films that have been winning of late have been pretty average.

To her, the more impressive award for the movie to have won was the Palme d'Or in Cannes where the competition is bigger.

I could understand her point of view, but to my mind this cast the movie only as interesting and watchable.

I was still unable to figure out why it has received the sort of adulation that it has.

The Washington Post review referred to something that I had not thought of. The reviewer wrote that 'the Parks (the wealthy family) are also, in a way, leeches, using the hired help to fill the nurturing and emotional roles that they can't -- or won't. It's a zero-sum game'.

This is interesting as an observation, but the reviewer doesn't offer more, and I didn't think there was any more to it.

The Guardian theorised: 'The servant is someone with an intimate knowledge of his or her employer, and yet this intimacy is so easily -- and inevitably -- poisoned with resentment.'

'There is a licensed transgression in servitude, and this transgression is nightmarishly amplified when it is a question of an entire family seeking to get up close and personal.'

'The poorer family see themselves in a distorting mirror that cruelly reveals to them how wretched they are by contrast and reveals the riches that could -- and should -- be theirs.'

'It is almost a supernatural or sci-fi story; an invasion of the lifestyle snatchers. Parasite gets its tendrils into you."

I sort of understand this, but think it is an elementary observation of the first order. The opening line about servant and intimacy will surprise no middle-class Indian. The rest of it is what I am unable to pick apart.

That leaves me with a final, alarming thought about why I am not able to 'get' Parasite.

Are we too close as well-off Indians, all with servants and drivers and tuition teachers ourselves, to be able to understand why it is all so awful?

© 2025

© 2025