'There is no way you can view the movie from a distance, from a moral high ground, and get to its core.'

'To truly appreciate what Anurag Kashyap is trying to do here, you may have to lose a part of yourself to it, first,' says Sreehari Nair.

Anurag Kashyap's finest movies -- Gangs of Wasseypur, Ugly and even Black Friday -- all work best, when viewed as comedies.

Human follies that go hand-in-hand with the most heinous of human crimes are what interests Kashyap the most; which, in a way, is Sriram Raghavan's shtick as well.

It's when these natural farceurs, easily two of the most exciting filmmakers making Hindi movies, turn to abject rationalising, that their movies disintegrate.

Kashyap, in particular, scrapes out his greatest moments straight from his unconscious and his blandest moments from that adult-part of him that tries to piece his painterly imagination together, tries to make his plots work.

The director's latest, Raman Raghav 2.0, features some of his best work and also some of his worst. It's not a glorious failure of the order of Bombay Velvet, but a largely imperfect success.

With this movie, Kashyap has probably made his most essayistic work to date, journeying across the treacherous terrains of psychopathy, trying to make sense of the essential boredom that spawns the sickness and linking it back to the city that gives it its shiv.

There is no way you can view the movie from a distance, from a moral high ground, and get to its core. To truly appreciate what Kashyap is trying to do here, you may have to lose a part of yourself to it, first.

Operating on two levels, RR 2.0 tries to both delineate the concept of psychopathy and also expose the general hideousness that exists in the most dull-seeming human beings.

Vasan Bala's script is divided into chapters, and the episodic narrative helps bring the movie together in your head. However, the structure also has a thematic importance. The chapter titles may sound like those of a pulp novel -- with their meanings often condensed into a single word -- but in their detailed readings, the chapters take us through the stages of psychopathy.

At work here is an attempt to shatter the belief that 'because evil is so bad it needs nothing more than a scornful look.' Our scornful look is the pulp from which Kashyap and Bala try to uncover a few tragic truths.

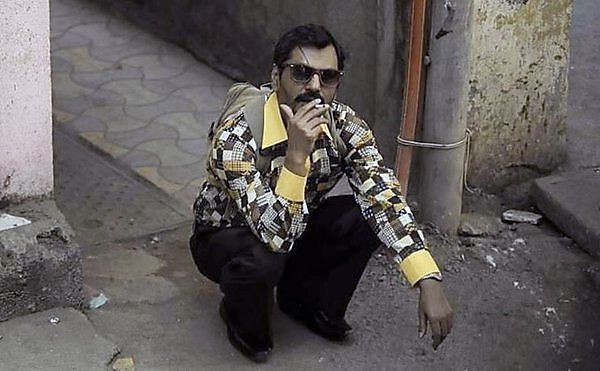

So there's Nawazuddin Siddiqui's Ramanna, a psychopathic killer with a philosopher's curiosity. If his back story is not explored, it's because back stories aren't for psychopaths like Ramanna who exist in what is known as the 'enormous present' -- and it is this kind of existence that gives such psychopaths, the narcissistic detachment of philosophers.

Ramanna's psychopath is also different from the psychotic in that he is not certified insane. This means he is not only interested in the dangers of his psychopathy, but also in codifying a separate universe in which his impulses could be worked out.

When he confesses to his crimes at the start of the movie, he gives that act the comfort of a tattered, incoherent narrative, which the policemen mistake for a psychotic's 'wayward tale.' But Ramanna obviously knows better.

With every kill, he wants to leave behind more than just the dead; he is also painting a blood-dripping graffiti of his ideas for the world. And those tales are actually the prologue to his graffiti.

In the titular sense, he is not very different from Travis Bickle, but their synapses are distinct -- he is Travis turned inside out. They both take direct orders from God: Travis is 'God's Lonely Man' while Ramanna refers to himself as 'God's CCTV Camera.'

But while Travis Bickle intended to purify the world by washing the scum off the streets, Ramanna wants the streets to be restored to their natural, primitive, animalistic order.

His communications with God tell him that in a mean, godless world, it is the old ideals that must die first: The natural innocence, the purest loves, the closest relatives. And so he scours the streets, the pathways and the alleys, looking for the perfect kill.

He searches for the perfect kill because he knows that only that will lead him the perfect orgasm. Yes! At the bottom of every psychopath's existence is a search for orgasm, greater than the one that preceded it; for orgasm is his analyst's couch.

This aspect of psychopathy -- murder as a link to the perfect orgasm -- is strongly hinted in Raman Raghav 2.0, and that is what makes this one of the most potent studies of evil in Hindi movies yet.

In this linkage, Ramanna meets his double, Raghavan -- a cop who is himself tethering on the edge of psychopathy, but whose evilness does not have the elaborate rituality of Ramanna's.

Vicky Kaushal as Raghavan doesn't just play a character with markedly different calibrations than the one he played in Masaan, he, also, seems to have broken down his insides and rebuilt them for this movie.

Kaushal has an inherent wide-eyedness about him and, here, his glasses that never come off contribute as much to his character as his posture that's laboring as opposed to sprightly.

Ramanna knows that Raghavan shares with him that yearning for the perfect orgasm. And so, when the psychopath watches the cop, as he has sex with his girl (Sobhita Dhulipala in a masterful debut performance), he announces: You are searching for what you desire, but in the wrong place. It's a telling line.

Another brilliant line comes toward the end of the movie when Ramanna goes off in his stream-of-consciousness style, doing the whole Pulp Fiction routine of 'And it's the world that's evil.

And when Nawazuddin does that routine, and one of Raghavan's cop-colleague acts all flustered, Nawaz shoots back with his Nawaz-like salivary honesty: Aap Baatcheet ka Rass nahi Samajhte (You just don't get the essence of this little chit-chat).

Ramanna understands that the evil this society wants to clean up, and the evil man that society is trying to make over in its own clean image, both lie outside the bounds of 'Crime and Punishment.' Because he is equipped with this knowledge, he sees himself as a hip in a world of squares.

And 'Aap Baatcheet ka Rass nahi Samajhte' points us to the fact that evil is a far more complex subject than what we make it out to be in our little poems that denounce terrorists, murderers, passion-killers, psychotics and psychopaths, and try to bring them under -- in pure marketing terms -- 'one umbrella.'

Raman Raghav 2.0 moves to the rhythm of its bodies, and it's when the bodies and the lips stop moving, that the movie's instincts become impaired.

When Kashyap circles around his newly acquired obsession for enshrining a moment -- either by slowing the action down, or, by adding a background score that attempts to spell the nihilism out to us -- the movie fizzles out. A scene with a drug dealer seems both overwritten and under-thought.

It's when Kashyap's camera records and doesn't try to interpret, that the juices work themselves into the picture. The high-angle shots create patterns within an image (a beat-up colony with all its particulars, its browns and its greens, and some men moving around randomly) and they are mixed with quick low-angle shots that convey a sense of immediacy and dynamism -- suddenly putting us at the centre of the action.

The details don't seem inserted and they work like natural fits -- like, that image of dust particles floating in front of a torch-light, inside a slum. Kashyap has taken a significant budget cut to get this movie made without interference, but the economy of style seems to have fired up his imagination. His personal cinematic orgasm probably has its source in crumminess.

There is a sense of heat in the pulse of the movie and it also has a wet look, and together that creates a sense of fermenting evil.

A just-pulp, more sadistic movie would have shown us the gore and the mayhem upfront and further made sure that we don't identify with the victims. Here we have Sobhita Dhulipala and Amruta Subhash, two victims, whose inner reservoirs of strength are what rattle the meanest of men.

This is a movie not interested in giving you the kicks and the payoffs. Even when the faces of Nawazuddin and Vicky Kaushal merge, they seem to be caught in a moment of transience, on the edge of a breakdown.

The movie also takes the idiom of the original Raman Raghav and discovers a modern day context, in which to disperse his spirit. The city is, perhaps, as crazy as the serial killer, and the rants of the original 'madman' might even read like sections of a philosophical thesis today.

This is, also, precisely why Nawazuddin's performance as Ramanna cannot be clubbed with his past performances. The brilliance of the actor's psychopathic turn, here, lies in his ability to convince us that Ramanna is acting out his wickedness in a world, where the wicked people operate in the most rational manner.

Ramanna is a winner because his wickedness is irrational, motiveless and set in the theatre of the silly. And yet Nawaz plays him like a sad winner who isn't crying out for our natural sympathies; playing him as someone who is always left with a cigarette, but not a single matchstick with which to light it.

The absurdity of the contemporary wasteland has always been the subject of Kashyap's best comedies. Here that fascination is padded up with a Norman Mailer-like investigation of the contradictions in the absurd. And in the process, Kashyap seems to have set free a bunch of new themes which he dives into but never fully explores.

I have a feeling that Anurag Kashyap will always be a director to whom resolution of conflicts will remain a mystery -- he is, maybe, too much of a proud artist to suggest resolutions.

This means that for all its daring and its cunning, RR 2.0 is also an unfinished movie -- a movie that Kashyap will, perhaps, complete only later in his career.

It's always said about Brian de Palma, how Blow-Out represented a culmination of all his obsessions. Even Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets had clear echoes of his own Who's That Knocking at My Door and his early shorts.

Maybe, like the original Raman Raghav, RR 2.0 will also have a spiritual successor (not a remake, mind you) which, will, somehow tie up all the discordant bits that make up this movie. But even when that happens, what we will have on hand is a movie which will demand that we give ourselves over to it.

The big factor determining our involvement, even then, will be our response to that ominous call.