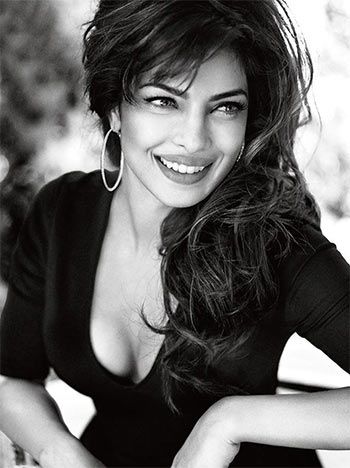

Priyanka Chopra, Irrfan Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui make a global statement on the power of Indian cinema, says Vanita Kohli-Khandekar.

What do Priyanka Chopra, Irrfan Khan, A R Rahman, Resul Pookutty and Nawazuddin Siddiqui have in common?

Chopra plays the lead in ABC's FBI drama Quantico that opened late in September this year. Most of the American reviewers seem to have trouble with the show's plot and its holes. But there is no questioning of why an Indian actor was cast in the lead role.

Khan has been the choice for several mainstream international projects -- The Amazing Spider-Man (2012), Life of Pi (2012), Jurassic World (2015), Inferno (releasing 2016) among others. Rahman has performed and composed with/for Andrew Lloyd Webber's Bombay Dreams, the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Mick Jagger to name a few.

Siddiqui was invited by the late Roger Ebert, an American film critic and cult figure of sorts, to the week-long Ebertfest, his annual film festival in Chicago in 2012. Among Siddiqui's international projects being filmed is the Nicole Kidman-starrer Lion.

The acceptance of Indian talent in mainstream Hollywood, British or Canadian projects is worth noting, precisely because there has been so little fuss about them in the markets where these are produced and where they make a bulk of their money. It speaks of a slow, soft globalising of Indian cinema and its talent, born of an unusual combination of factors.

On the one hand there is the old 'India is a big growing economy, successful expat population' argument. But the real reason, to my mind, lies in the growth of the Indian film market and its extraordinary creative and commercial resilience.

Somewhere in the 1970s, Kabir Bedi and Persis Khambatta went to Hollywood. Bedi got a role in the James Bond film Octopussy (1983) and Sandokan (1977, a popular TV series), among others. Khambatta was part of Star Trek (1979) and Nighthawks (1981) among others. But largely, Indian cinema and its talent were focused on the local market. It was a tough time for the industry -- financially and creatively.

After liberalisation, the TV arms of 21st Century Fox (Star India) or Sony and the growth of local firms such as Zee and Sun showcased the possibilities in an entertainment-crazy market. Soon the film business got industry status and multiplexes a tax break in some states.

Multiplexes and single-screen digitisation meant computerised ticketing and, therefore transparency. All the revenues came back into the system instead of leaking out. The total revenues of what was seen as a dead industry grew nearly threefold over a decade.

This unleashed a creative spirit that is now experimenting like the industry did before the break-up of the studio system in the 1950s. Johnny Gaddaar (2007), Kai Po Che, Vicky Donor, Oh My God! (all 2012) The Lunchbox (2013), Mary Kom (2014), Talvar (2015) (left) are among a rising number of films that tell good stories and tell them well. India is becoming a name to reckon with at several international film festivals.

This unleashed a creative spirit that is now experimenting like the industry did before the break-up of the studio system in the 1950s. Johnny Gaddaar (2007), Kai Po Che, Vicky Donor, Oh My God! (all 2012) The Lunchbox (2013), Mary Kom (2014), Talvar (2015) (left) are among a rising number of films that tell good stories and tell them well. India is becoming a name to reckon with at several international film festivals.

Note, and this is the key point, that India, China and Korea are the only markets with a strong local film industry that haven't been swamped by Hollywood. However, unlike China or even France, India has no quotas or restrictions on importing foreign films. There is no State support for cinema. Yet, over the decades Hollywood's share of the Indian box-office has remained stuck between five and eight per cent. Its resilience and growing size (Rs 13,000 crore currently) prompted majors such as Disney and Warner Bros to set up production studios for local films in 2008.

The creative idiom emanating from this financially healthier, confident, outward-looking Indian film industry is totally its own. It is this idiom that is giving rise to films such as Miss Lovely (2012), Piku (2015), Court (2014) and dozens of others. And it is from this confident Indian idiom that actors such as Chopra and Khan are being picked as a matter of course, because they fit the role, not because they are Indian or because Hollywood films do well in India.

You could argue, like many creative people do, that why hanker after Western acknowledgement. But just like competing and winning in the global market for software or tech services make for economic and emotional feel-good, so does this one.

Chopra, Rahman and company do India proud in the super-competitive global market for entertainment. That certainly is something to celebrate.