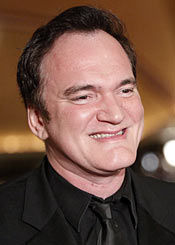

As Hollywood director Quentin Tarantino turns 50, Raja Sen comes up with a light-hearted write-up on what would happen if the director decided to make the Bible no less. I always picture Quentin Tarantino as holding a fountain pen like one would a samurai sword, poised over a foolscap sheet, dripping with righteous fury.

I always picture Quentin Tarantino as holding a fountain pen like one would a samurai sword, poised over a foolscap sheet, dripping with righteous fury.

The strokes would be mercurial and defiant, badly spelt brilliance creating wordpictures unlike any we’ve seen before. Pictures that pay tribute while surpassing the old, pictures that borrow and appropriate, pictures that distinctly and unmistakable belong to that one audacious auteur.

As Mr Tarantino turns 50 -- and alarmingly contemplates retirement in a few films time -- he continues to shock and dazzle, to make us flinch and make us feel, and to surprise us with the power of word and image. His most recent release Django Unchained, hit Indian theatres just six days ago and -- despite its criminal censoring -- is a film you should rush to theatres to experience.

Now to pay homage to the master, I offer up a favourite blogpost I wrote back in 2004. (For what better salute to Quentin than freshly presenting a dish served old?) Written to lampoon Mel Gibson’s painful The Passion Of The Christ, it is a meditation on the Bible as seen through the Tarantino lens: his films and characters and trademarks all feature, but do remember this is from a time before Kill Bill Volume 2. (Now, as he reshapes history to his needs with his new revisionist masterpieces, I keep wishing he would take on the big book.)

From a much younger me to a director I hope remains a cinematic brat, Happy Birthday Quentin Tarantino. Ears to you.

The Gospel according to Quentin

The credits set the tone for the film: classic, Cecil B DeMille titles: bright, gaudy, gold, larger than life; epic credits. The first credit is characteristically the directorial one, and it is this that at first shocks us and then explains the director’s vision, the scope of his universe. ‘The First Film By Quentin Tarantino’, it screams, in massive serif letters. While this momentarily confuses us, having lived through his last four/five (varies by degree of purism) films, most fans of the director will comprehend the ironic overstatement immediately.

Quentin’s is a parallel universe: a world where Mr Blonde, Sidewinder, The DiVAS and Fox Force Five can, and do, coexist separated merely by the confines of space and time. Considering this, we realise that he is making a statement of chronological accuracy: set more than two thousand years ago, this film predates all his previous efforts. Brilliance thus begins in the very first frame of film.

We open on The Last Supper, where, amid bread and wine and an enviable selection of main courses, the disciples are impassioned in debate. The topic under discussion is the Madonna's new-found status “as a Virgin”. Evidently, conspiracy theories have been around for a while, and winks and nudges are exchanged across the table. Jesus (Steve Buscemi), for whom this ribaldry is an obviously awkward subject, decides to proceed with the momentous evening by breaking the ridiculously priced bread into small pieces and passing it around the table. The disciples graciously accept the pieces of loaf. All but one, that is.

“I don’t believe in sharing.” The camera moves towards one of the younger acolytes, with a straggly stubble and clad in long, flowing, orange robes. This is Judas, played masterfully by Tim Roth. His story – of betraying Jesus, lured by dreams of buying his own state-of-the-art chariot, a thundering Roman vehicle called a Chopperus, is told instantly, in quick, non-linear cuts, interspersed with shots of a sack of golden coins, the sestertii scattering onto him in super slow motion as thrown to him by the Romans.

The several-voiced, multiple-thread narrative of The Book lends itself perfectly to Tarantino’s typical back-and-forth shuttling through various levels of flashbacked past and present. The Nativity scene is a stunning work of anime, chronicling the arduous travels of the Three Wise Men, played, in their subsequent live-action avatars, by David Carradine, Samuel L Jackson, and Lucy Liu [who, the illustrations elaborate, became a Wise Man after a successful coup, and is open to most critiques except those questioning her ascent to ‘Man’ status despite being a woman]. In fact, her role among the three is particularly vital, as, being the woman, she turns out to be the only one who remembers the date and drags the other two to Macy’s in order to shop for the Saviour’s birth. Jackson carries the most cryptic of gifts, the mysterious Myrrh, in a black briefcase, and it is enigmatically not shown – only opened off-camera, greeted by appropriate oohs and aahs, casting a divinely strange glow across witnessing faces.

Pam Grier plays Mother Mary, in a startling bit of miscasting. Apparently, while Tarantino plodded through The Book and wrote the screenplay, he envisioned her throughout. Later, while realising that Mary wasn’t supposed to be black and, as a result, didn’t entirely complement Robert Forster (Joseph), he decided to ignore his initial oversight, convinced she was ideal for the role. She plays a strong, determined character, a firm mother with affection largely visible only between the lines, a Mary displaying stoic conviction and belief in her son. Stirring.

Harvey Keitel rejuvenates the role of John The Baptist, a severe taskmaster who mentors Jesus in order to prepare him for the ordeal that eventually awaits him. There is a scene, before the storming of the Temple, where John yells at the indecisive Disciples, and Jesus winces. On hearing that there is no need for aggression, The Baptist patiently elaborates on their task being single-mindedly crucial, and apologises inimitably, in a manner that makes the Messiah automatically take back his complaint: “If I have been curt, My Lord, I apologise,” begins his inspiring speech. He details the inevitable need for violence immediately ahead of them – this is superbly humane, speaking of ‘the greater good’ that will be served by mercilessly bludgeoning the evil usurpers of The Lord’s Temple. He finishes with a heartwarming smile, and suggests that the Lord pluck some fish and loaves, for they are famished.

The compelling catastrophe is a particular favourite of the auteur director, and Quentin has previously displayed his fondness for tremendous scale. The Storming Of The Marketplace is, therefore, a visually chaotic work of cinematic poetry, with thwacking staffs and a surreal, mighty Buscemi, dragging grubby vendors by their long, unkempt beards. When the violence of the clash becomes overwhelming, the filmmaker shifts to black and white, imparting an ‘apocalyptic dream-like’ quality to the sequence. Tables are shattered, gold is spilled; sandal-crushed vegetables and wine litter the floors, remarkably resembling splattered brain and intestines spread in blood. There is a poignant moment when one of the Wise Men, in a queerly timed reappearance, walks in and witnesses the carnage. He takes a deep breath and stands back and waxes profound: “This is some repugnant waste.” Unforgettable cinema.

Mary Magdalene (Uma Thurman) follows Jesus around with great, visibly heartfelt devotion. After her salvation from sin, she is now clad in modest attire, covered head to toe in a yellow robe. Uma has compelling, powerful eyes, and Tarantino makes excellent use of these as he constantly zooms right in, once even to reflect a resting, exhausted Messiah prostrate within them. Most of her finest moments on screen are wordless, and particularly memorable is the emotive shot where she explains the fate of The Saviour to Grier. As The Virgin looks on inquiringly, Thurman simply traces the shape of a cross in the air – Quentin helps us by following her fingers with dotted, white lines – and smiles a bitter, wry smile.

Jesus, captured by the Romans, is taken to see Pontius Pilate. Here is where the director takes us on a breathtaking rollercoaster ride of a single-take long camera shot, one that moves through the streets, catches up with The Messiah, moves to shoulder level as he walks nonchalantly along, loiters momentarily on Satan walking by – tempting Jesus with a bushel of evidently delicious red apples, pans around slowly to capture the jeering ex-pressions of the onlookers, before pulling majestically upward to reveal the procession entering the gates of Pilate’s palace.

In what has now become a trademark cameo, Quentin steps in front of the camera, this time to play Pontius Pilate. His Emperor is one with churlish arrogance, and a royal lack of humility, something the director seems comfortable portraying. He insouciantly snarls: “Do you see a sign here saying ‘Blaspheming Judean Storage’?” as the beaten Jesus staggers forth, and disgustedly strides off to wash his now-bloodied hands. Reluctant, and apathetic, at first, to dole out justice to the seemingly insignificant Buscemi, he is later aptly malevolent when deciding in favour of the awful punishment.

And then there is the torture. The violent, sickening, emotionally draining torture of watching Jesus battered by the ruthless Roman guards. Particular attention is given to two soldiers, the brothers Vagueus. Gripping cinema is created as the younger brother Flaxenus (played to sinister supremacy by Michael Madsen), having whipped and bled the Messiah without reprieve, pulls the thorny crown onto Jesus’ head. Here, as we turn away from the screen, collectively flinching, the camera does the same, and succinctly slides away, hiding the gruesomeness we all know. What this technique essentially does, of course, is just conjure up the scene inside our heads with an alarming attention to graphic detail impossible to show on screen. Yet the director cannot be faulted for trying to shield us from trauma, in his own way.

Tarantino films are, beyond being stylistic orgies of cinematography and soundtrack, primarily composed of pure dialogue. Of violent people in lethal, frightening professions we eventually identify with, and even, begrudgingly, like, owing to realism, the commonplace coarseness, the conversations that we can visualise ourselves participating in. Here, too, as the older brother Vincentus (John Travolta) puts the Crucifix together, he complains at the ridiculous price of timber. The comments bring his existential humanity into perspective for the audience, as he shakes his head at a five-sestertii 2×4. As he nails the cross, sweating and tired, half splattered with The Messiah’s blood, he concedes that it is really fine wood. However – five sestertii? The brothers laugh as they pile on the pulverised, near-dead Jesus onto the carved wood and Flaxenus throws us another gem of cinematic dialogue as he phrases it with deadly accuracy: “This is no ordinary execution, my brother. This is Pulp Crucifixion.”

The final scene is presented to a weary wreck of an audience – shocked, overwhelmed, humbled. In the darkened theatre, having undergone a life-altering cinematic experience, you sit surrounded by sobs. Even though some of these are from film-school students coming to terms with their years at UCLA having been rather pointless, the feeling you get is one of overpowering sincerity. Jesus hangs on the cross. The sky thunders furiously, the storm drowning out all sound. Even the huddled masses by the base of the cross have begun to disperse, for night has fallen, and the rain is hard. Blood from the lifeless Messiah’s body is scrubbed away, as are onlooking tears.

There is an extreme close up of a crying Uma Thurman, mouthing words as she sobs forcefully into the squall. The downpour does not let us hear her words, but the camera lingers on her impassioned lips as she repetitively chants the prayer of a true believer, unwilling to accept the fate reality has forced onto her. The words become increasingly clearer as we move into slow motion, and are drilled into our brain as she incessantly goes on.

Wiggle. Your. Big. Toe. Wiggle Your Big Toe. Wiggle Your Big Toe. She continues to will him, ad infinitum. The camera ultimately closes in on the Toe in question, hanging lifelessly, lashed by rain. As the rhythm of Mary’s unheard chant has been drilled into our collective consciousness by effective, manic repetition, we feel ourselves willing the appendage into motion as well. The shot remains static for three glorious minutes, as music from an old spaghetti western builds magnificently to a crescendo.

Then an incandescent white screen is suddenly thrust onto us, momentarily blinding the audience, accompanied by a particularly resounding clap of echoing thunder. Then all is silence; all is utter darkness.

The movie is over. And cinema will never be the same again.

Photograph: Jim Tanne/Reuters

© 2024 Rediff.com -

© 2024 Rediff.com -