'Sent off to interview him in the late 1970s I met him in a cafe in New Delhi's Regal Building called The Parlour. With impromptu send-ups of Laurence Olivier, Sybil Thorndike and the rich, gravelly tones of a well-known All India Radio Hindi newsreader called Devki Nandan Pandey, he soon had the whole restaurant listening in.'

Sunil Sethi remembers the amazing Saeed Jaffrey.

The pleasure of knowing Saeed Jaffrey was that he was at least as great an entertainer in real life as he was on radio, television, stage and film.

The pleasure of knowing Saeed Jaffrey was that he was at least as great an entertainer in real life as he was on radio, television, stage and film.

Acting, of course, requires reserves far greater than mimicry or a mere replication of reality; but Saeed, whether in a group of close friends or even an audience of one, could be a ventriloquist's dream and raconteur par excellence.

In lean times when he eked out a living as a freelance broadcaster at the BBC in London he once read a short story from Sri Lanka, convincingly impersonating each of the 26 characters with a sound track of sonorous Buddhist chants in echoing bass and tenor notes.

The announcer turned to Saeed to ask who the cast were apart from him and was dumbstruck to learn that it was a one-man production.

Sent off to interview him in the late 1970s I met him in a cafe in New Delhi's Regal Building called The Parlour. With impromptu send-ups of Laurence Olivier, Sybil Thorndike and the rich, gravelly tones of a well-known All India Radio Hindi newsreader called Devki Nandan Pandey, he soon had the whole restaurant listening in.

He came armed with a treasure trove of redoubtable chestnuts. Among them was how in 1972, on a stopover at Beirut airport, he spotted Satyajit Ray writing postcards. The short-statured Saeed tore across to accost the imposing six-foot-four frame of the director, obsequiously introduced himself -- he had a great line in flattery -- and asked, 'Is there any chance, Sir, that one day we might work together?'

Mr Ray was charmed and said he had heard his excellent readings of Wajid Ali Shah's letters to his Begum on the BBC World Service. 'I know you're good at waiting, Saeed. So please wait. It might just happen.'

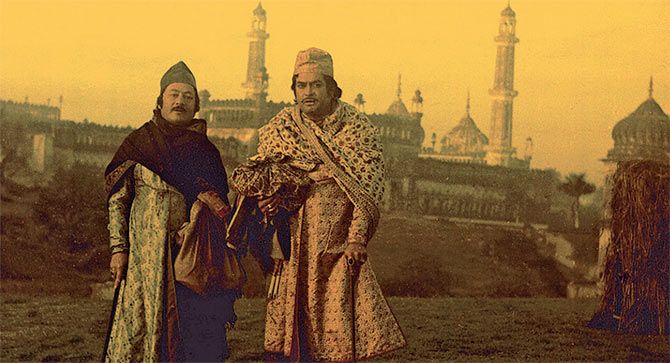

Three years later, in the master's elegant calligraphic hand, came the letter inviting him to play Mir Roshan Ali, the Avadh nawab in Shatranj Ke Khilari -- surely one of the stellar performances of his multi-media career.

His personal style was marked by a slightly gushing manner: The effete cadence of an Uttar Pradesh taluqdar overlaid with the campy 'darlings' and 'sweethearts' of a certain vintage of British stage and film folk.

His friend and fellow broadcaster Mark Tully recalls how Saeed swept in while he was laid up in a London hospital's public ward with broken ankles.

'To the horror of my mother, who was visiting at the time, and the amazement of the other patients he embraced me, kissed me on both cheeks, and said, "Mark, darling, how terrible. I'm missing you so much, you must come back to us as soon as possible." It took me some time to persuade my mother that this was the way Saeed greeted all his friends.'

Saeed Jaffrey, in fact, was an ardent and serial lover of women. His autobiography Saeed: An Actor's Journey, (HarperCollins, 1999), despite its workaday title is a colourful, often racy account that pulls no punches.

In it he recounts (with unusual candour for someone deeply rooted in the art of the make-believe) the remorse that filled him when his marriage to the gifted Madhur broke down irretrievably in New York on account of his roistering, and she left him with their three small daughters.

They had met in amateur theatre and AIR circles in Delhi in the 1950s -- he the son of a provincial doctor in Uttar Pradesh, she from a wealthy Old Delhi kayastha family -- and when she won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art he pursued her westwards on a Fulbright to study drama and play in American reps.

Having burned his boats in America he relocated, penniless, to London, living in cheap digs and supplementing periods of unemployment by working as a bar tender and Harrods salesman.

But his unflagging energy and commitment to his art never wavered; he took on all jobs, big and small, building up a staggering repertoire that ranged from the Gurkha soldier Billy Fish in John Huston's The Man Who Would Be King to Suri Sahib, the Punjabi parvenu in Shekhar Kapur's Masoom and Nasser Ali, the rakish Pakistani entrepreneur in Stephen Frears' My Beautiful Laundrette.

His chameleon-like ability to switch accents, guises and genres made him a proper study as a character actor and, in time, a star.

When Gul Anand and Sai Paranjpye offered him the role of the paanwallah in Chashme Buddoor, he took them to Jama Masjid to choose his costume. 'Then I borrowed my dialogues, gave the character a name, Lallan Miyan, and rewrote all my speeches in the authentic 'Cockney Urdu' of Old Delhi.'

His second marriage to the casting agent Jennifer Sorrell ushered in a period of stability and deep companionship. His was a long, rich life lived to the hilt.