'Ashutosh Gowariker's Mohenjo Daro does what many history books could not have done.'

'He awakens interest in the ancient civilisation of Harapppa and Mohenjo Daro,' says Asim Siddiqui.

Ashutosh Gowariker's Mohenjo Daro tries too hard to blend prehistory with a popular story to appeal to an intellectual audience interested in serious subjects and the masses brought up on a regular diet of songs, dance, drama and action.

The result is that neither side appears too pleased which does appear a bit unfair simply for the kind of effort that must have gone into the making of this ambitious film.

There certainly are many cliched situations in the film. A rebel raising his voice against injustice and the machinations of power is a formula which has been repeated too often in our films.

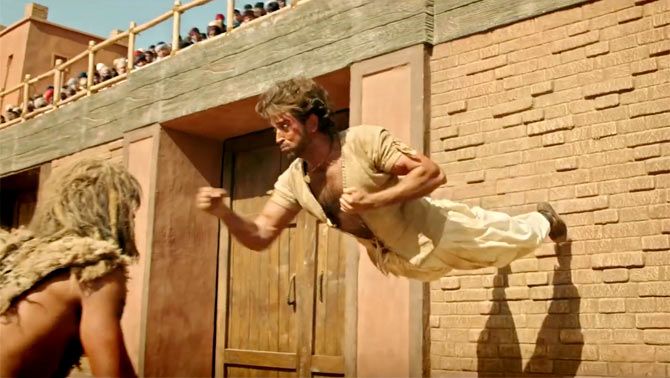

The lost rightful heir has appeared in film after film in our cinema. The hero made to pass an impossible test, it may be a fight against a lion or an oversized brutal demon-like man, is also a formula that had been perfected by Dharmendra and sons, though this Lagaan moment in the film 'Pariksha sweekar hai' does have its attraction.

Ever since the film's trailer was out, the film came under attack for playing with facts of history, especially in promoting the Hindutva view of history.

The trailer announced the setting of the film in 2016 BC, with a voiceover declaring the action of the narrative taking place before the British Raj, before Mughal rule, before Christ, and before the Buddha but avoided saying before the Vedic Age.

Then there were the rampaging horses in the trailer, the animal associated with the Aryans, which alerted critics.

The trailer was certainly not the complete picture. The film starts with the disclaimer that there are different views about Harappan civilisation and this gives Gowariker some freedom which he further mixes with his artistic licence.

Obviously Gowariker is not writing a history textbook but making a period film which should both appeal and entertain a big audience in 2016 and do good business.

In any case, as historian A L Basham says 'Our knowledge of the Indus civilisation is inadequate in many respects, and it must be classed as prehistoric, for it has no history in the strict sense of the term.'

But surely enough Gowariker succeeds in drawing attention to India's many continuous cultural traditions the appeal of which can still be felt.

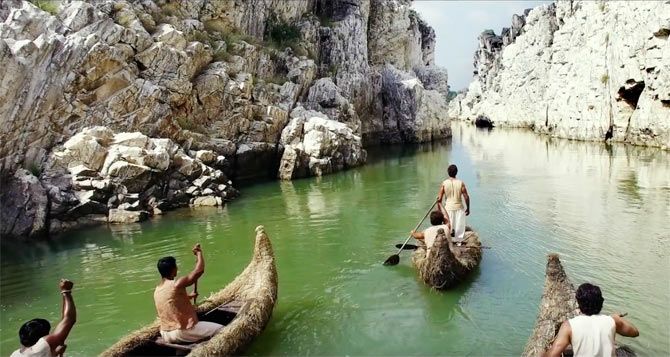

The very first scene of the film shows Sarman (Hrithik Roshan) rowing his boat which is attacked by a flying crocodile. The remarkable thing about this scene is that it establishes a sense of distance between 2016 BC and AD 2016.

If the presence of the crocodile evokes an exotic image of distance, the primitive man's smelling the danger even before it has appeared does it even more intelligently.

Even when he is not all the time faithful to whatever is known about this history, Gowariker does manage to give some useful glimpses of the most ancient civilisation of the subcontinent.

The camera focuses many times on Mohenjo Daro seals and inscriptions the language of which has not been deciphered yet. In the same way the scenes showing planned architecture of Mohenjo Daro with its two-story houses of baked brick is a treat to watch as are the scenes of the marketplace which present the nature of trade in the city.

That the city invested in trade and it had trade relations with other contemporary civilisations like the Sumerian is also aptly communicated by the film. Mohenjo Daro's famed public bath about which a lot has been written, shown in a song, may be mistaken for a swimming pool.

The excavations at the site revealed that Mohenjo Daro had a citadel on a platform and a town proper. This lends an opportunity to our filmmaker to take up the subject of class division as all films explore some kind of conflict for dramatic effect, most importantly between the poor and the rich.

The film highlights the difference between the upper and lower city and consequently between the poor and the rich, pitting the hero against the villain.

Gowariker's film uses many uncertainties about historical facts very intelligently. It is a point of debate whether there was a centralised rule in this civilisation or democracy flourished from different institutions.

Gowariker shows both. The democratic institutions in Mohenjo Daro are represented in the meeting where heads of different professional groups voice their opinion freely and voting is the means to arrive at a decision.

When Sarman finally achieves his final victory over the villain, he refuses the control of Mohenjo Daro in favour of the common people. But there was no mistaking a centralised rule in Mohejo Daro as is shown by various arbitrary announcements from the ruler.

Day to day life is also captured by the camera. The headgear associated with Mohenjo Daro women sits beautifully on the heads of dancers in the film, particularly on Chani (Pooja Hegde) who cannot be recognised by ordinary folk when it is not on her head.

As for the food, from one brief pan shot of the spread one is left a bit uncertain about the food choices of the people of Mohenjo Daro, though there does appear, apart from other eatables, what looks like grilled fowls.

Though it was not part of their life, the presence of the horse in Harappan civilisation has not been ruled out; in the film the horse is brought from the Central Asian city Bukhara (Uzbekistan) and it is a display item for the rich and a curiosity item for ordinary folk who are not familiar with this animal.

Of course, the filmic device of the hero taming an uncontrollable horse, that too when the horse threatens his beloved, proved too attractive to resist for Gowarikar.

The issue of the use of Sanskritised Hindi in the film has been criticised on ideological grounds. It was certainly needed because a slightly unfamiliar vocabulary at some places can convey the sense of distance better than a very familiar dialect.

In the climax Gowarikar tries to introduce the contemporary issue of the displacement of population because of the building of dams. However, by moving the population of Mohenjo Daro to a different location because of heavy floods, Gowariker flirts with many historical opinions about the decline of Harappan civilisation.

He stays clear of the view that it met its end because of Aryan invasions. He rather focuses on natural causes and man-made cause of changing the course of the Indus river to appeal to a contemporary audience.

In between these scenes he stresses the use of boats and bullock carts in Mohenjo Daro to give a feel of the correct iconography of the city.

However, Gowariker's many choices to please the contemporary audience in 2016 appear of ideological nature. Of all the arms available to his hero he must choose a trishul to fight two deadly man-eaters from the hill.

But then which Bollywood hero did not use a trishul? The dead bodies in Mohenjo Daro, it is hinted, could be buried or cremated and the film highlights cremation. It can be questioned because Cemetry H culture dates from approximately 1900 BC to 1300 BC and the film is talking about 2016 BC.

In this phase of the Indus Valley civilisation, as many historians have noted, the dead in Mohenjo Daro were buried. Bringing in the discussion of Sir Mortimer Wheeler's pioneering work on Harappa and referring to the discovery of a cemetery and 57 graves, A L Basham writes in The Wonder that was India: 'It is clear that the dead were buried in an extended posture with pottery vessels and personal ornaments.'

Gowariker also uses his artistic licence in showing the unambiguous continuity between Mohenjo Daro and the Gangetic region. The last scene of the film has Sarman tasting the pure and clean water of the Ganga and asking his people to make their new home on its bank.

On balance Gowariker's Mohenjo Daro does what many history books could not have done. He awakens interest in the ancient civilisation of Harapppa and Mohenjo Daro.

Mohammad Asim Siddiqui teaches English at Aligarh Muslim University.