'The film industry could never exploit his versatile range as actively as it should have. To not have delivered a *single* bad performance in one's career is an exceptional feat.'

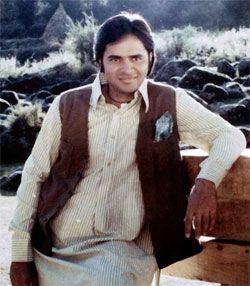

Sukanya Verma retraces her steps to the time she became a dedicated fan of Farooque Sheikh's work for life.

Even when I was too young to grasp the concept of films and make-believe, I was immensely fond of Farooque Sheikh.

Back then, I didn't have any solid reason to explain my attachment. Except that he bore an uncanny resemblance to my beloved Mamaji and filled the frames with his beaming goodness and bounce, which I could surprisingly appreciate even at that age.

I first saw him on big screen as the romantic Nawab Sultan in Umrao Jaan, but it was his accessible boy-next-door appeal, high on humour and lovability, in feel-good fare like Chashme Buddoor and Kissi Se Na Kehna that made my day.

Even as I devoured his glorious resume -- Katha, Picnic, Noorie, Rang Birangi, Saath Saath and Bazaar on Doordarshan or VHS, it would be a long time before I returned to the cinema halls again to view one of the not-so-memorable outings of his career.

In Manmohan Desai's 1989 superhero fiasco Toofan, he essayed the supporting role of Amitabh Bachchan's best friend (Don't Worry Be Happy, remember?). Regardless of Toofan's silly content, I felt god-awful about the tragic fate Farooque Sheikh's character Gopal meets in the story.

It took an unlikely film to confirm it; I adore Farooque Sheikh.

Oblivious to my affection, he reciprocated with his elegant artistry, disarming wit and multifaceted insights as a movie heavyweight, theatre personality, television star or celebrity anchor.

The more I watched him (especially his earlier work in Garam Hawa, Gaman, Shatranj Ke Khiladi), the more I understood his ingenuity. Regrettably, the film industry could never exploit his versatile range as actively as it should have.

To not have delivered a *single* bad performance in one's career is an exceptional feat. Even in absolute drivel lacking coherence and intelligence, he did not. No wonder he won his first and only National Award for an obscure release called Lahore.

In my career as a film journalist, I interacted with the biggest and the best without any trouble, but the mere glimpse of Farooque Sheikh would instantly transform me into an embarrassing version of Bashful the dwarf.

Once at a suburban multiplex, he stood before me in the snack queue (akin to Shah Rukh Khan's elevator scene with Juhi Chawla in Darr minus the stalker undercurrent), like a stereotypical, star-struck fangirl, I spontaneously nudged my finger on his crisp white chikan kurta.

To my surprise, he turned around and acknowledged this indefensibly childish gesture with a sweet smile. I would have recognised *that* smile in a crowd.

I would like to believe his smile spoke to me. That it valued my inaudible admiration. Unable to speak, I smiled back nervously and went on to order the most unforgettable popcorn of my life.

Though I never interviewed him, I am glad I expressed my awe for the man during his lifetime.

The news of his sudden demise is yet to sink in. But when a luminary is as precious and palpable as Farooque Sheikh, the loss feels undeniably personal.