'The non-cinephiles may hold up Sholay as their personal favourite and the cinephile lot may quote something like 8 1/2 as the movie to load with them on the ark.'

'But for a good percentage of these people from both categories, if there is one film to simply laze around with, a film that can extract them from their dull funk, it's definitely DCH,' says Sreehari Nair.

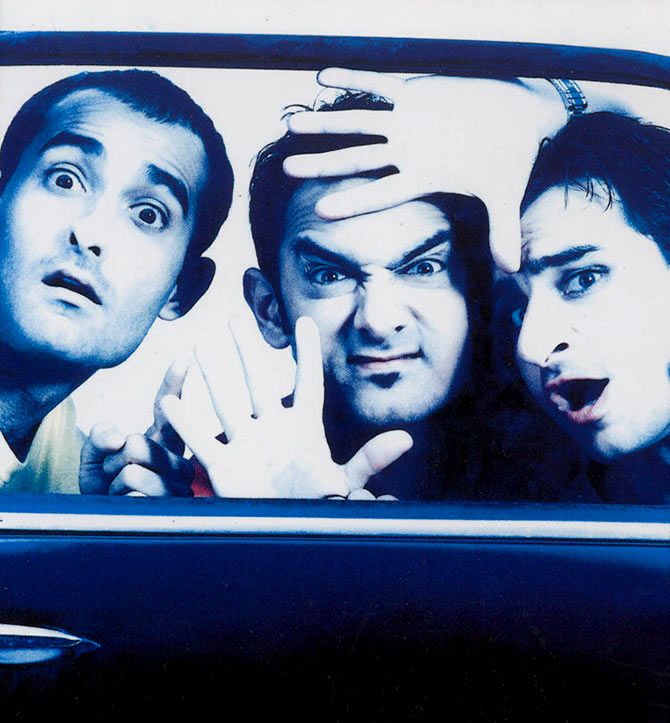

In the world of Sameer (Saif Ali Khan), Aakash (Aamir Khan) and Sid (Akshaye Khanna), the biggest sin perhaps is acting sappy.

Even Sameer, who suffers from constant lapses in romantic judgment, is no saphead and, with Aakash and Sid, he shares precise codes of coolness -- codes that don't adjust well to the image of a fully-grown man buying 'exactly one balloon' for his girlfriend at the same traffic signal, everyday.

Classically, this 'balloon-buying' would have translated into some sort of an 'Aww moment'; something for advertising to smartly funnel into the Hallmark Cards-loving part of our conscience. But when Sameer, Aakash and Sid ridicule it in their own chic way, we felt it was okay to join in and give the act, the public finger.

Watching it now, 15 years since it first released, Dil Chahta Hai seems as cunningly scandalous as it seems fresh.

Scandalous because, Farhan Akhtar's approach -- even to this date -- comes across as one in which he derives freshness from making small our grand ideals, choosing to glide past stuff that our movies have deemed important and placing emphasis on events that we would otherwise consider only secondary to the narrative.

It was specifically this approach -- a love for the movies fused with contempt for the movies -- that had helped Dil Chahta Hai bring in a new spirit.

When his camera stayed with Akshaye Khanna all the way through -- as Khanna tore along the road, collected his painting materials and sprinted back -- Farhan Akhtar was going against the cardinal rule of film editing: He was taking a 'straight snip', a moment of no real plot movement, and inserting it into a scene.

Now, 15 years later, we realise he was adding freshness there.

With (cinematographer) Ravi K Chandran, Akhtar works out a very specific look for the movie -- borrowing the ethos of its minty imagery partly from Nat Geo specials and partly from lifestyle magazines.

Dil Chahta Hai is , maybe, the first Indian movie that conveys affluence in a natural, non-expository, almost languorous sort of manner.

Upon my first viewing in 2001, I -- who had spent almost all my life in the suburbs of Mumbai -- found the differences in the characters' lifestyle and mine, glaring; and at times even eerie.

The furniture in the movie, for instance, looked like they were trying to reclaim from the people space which was rightfully theirs. The paintings seemed to have discovered their natural abodes on the walls and the lampshades were on the verge of talking. In one scene, the shot perspective suggested that a giant TV screen was ready to leap toward Aamir Khan and devour him.

If the differences in both our lifestyles and our definitions of living spaces existed, the wordlessness with which these differences were conveyed made the reality even more daunting.

For those to whom the lifestyle made sense, there was a joy in the identification. For the rest of us, there was another kind of joy; and when the end credits rolled, we went back to being ordinary again.

When the movie mimics the ability of the best documentaries to discover poetry in the mundane, it also proposes that the mundane can exist in a state divorced from any deep, underlying meaning.

So solving a Rubik Cube is just that. Doodling is just doodling. And if a linear shot of three friends driving on the Mumbai-Goa route hits you as too pussy -- 'well we have jump-cuts to iron out your boredom.'

Even the lechery seems classy and full of juices.

When the trio stare wide-eyed at a woman, they don't see her as 'food', but as an acknowledgment of someone who fits their definition of 'the perfect beauty'; something that awakens their senses and gives flesh to their mental poems. And yet there is no sense of finality that they seek from these women; there is nothing sentimental about the whole thing.

Their worlds are so clearly un-gooey that when one friend acts all schmaltzy, the other two immediately sense that he is being disrespectful of the silent code.

So when Sid slaps Aakash, he does so to snap Aakash out of his insensitivity, but for Aakash the betrayal exists as something deeper -- his friend was acting in a way that they've always maintained to be 'uncool.'

That slap is a dynamics-changer -- it's the kind of experience that usually pushes kids, who are constantly gutter-fighting and later making up, out into the adult world of long-standing grudges and bitterness. And from thereon, the movie suggests -- and quite rightly so -- that true adult world is one in which genuine emotions don’t get muted for the fear of being sentimental.

The post-modern shtick of turning everything into a joke is as unreal as the blaring display of mawkishness. And, as if he knows this truth, Akhtar maintains the balance just right, especially in scenes when the men get down to business with their preferred women.

In these scenes, and in varying degrees, it's shown that the women clearly love in the men, their boyish vulnerability and cheekiness; that the women are as interested in the world of men as the men are in theirs.

In return our three boy-men, who don't need to talk to each other much to get their chemistry going, have to figure out changes in their approach.

They play-act courtesy, loosen up and let go. And throughout this dance, the whole quasi-liberal call for 'understanding women' is mercifully given up for curiosity, grace, imagination and even an indefinable sense of eroticism.

Watching it again now, the real wincers in Dil Chahta Hai is everything that's spelled out (including a couple of very serious 'Main tumse pyaar karta hoons'). On the other hand, what still shines bright are the feathery stuff -- the silences that's zoomed into; the thinking up of thoughts that is captured; and passing expressions that are given their due.

If there is ever a Hindi movie that proves right the maxim 'Rhetoric is heard and Poetry, overheard,' this is that movie.

And yet, when the talks work up a rhythm, they are so absolutely freewheeling and the lines have such a bouncy quality, they cling onto your senses.

Audiences of this generation would probably enjoy the characters' way of conversing -- with puns thrown in randomly, one-word interjections and fast double-talk routines -- more than the earlier generations because a lot of the sub-culture vernacular of Dil Chahta Hai has today become the defining element of our everyday discourses.

There are even times when Farhan Akhtar the writer lampoons verbal tendencies that were yet to arrive.

Notice, as an example, the prescience in a mock-phrase such as 'naukri milne ke 100 tareekey' and how it acts as a precursor to some of the internet's most preferred headlines today: 4 things you should never do near your office water-cooler, 5 ways to check if your neighbour loves you as much as you do and so on.

Notice also how Akhtar's lines that work so well with the younger characters don't work as well when mouthed by the older characters.

Yes, Farhan Akhtar's loyalties lie with a certain demographic but, more specifically, they are stacked in favour of a certain age group. And all those outside that age group -- the parents, the uncles, the managers and the doctors -- are just stoic set-pieces.

Dil Chahta Hai is what most of my friends -- both cinephile and non-cinephile -- cite as the movie they would 'watch anytime.'

Ideally, the non-cinephiles may hold up Sholay as their personal favourite and the cinephile lot may quote something like 8 1/2 as the movie to load with them on the ark. But for a good percentage of these people from both categories, if there is one film to simply laze around with, a film that can extract them from their dull funk, it's definitely DCH.

As a popular art form, movies have always boasted of artistes whose artistry expresses an appeal that can unify all kinds of audiences into bellowing a collective approval.

With Dil Chahta Hai, Farhan Akhtar perhaps became that artiste very early on in his career, never to occupy the position again. And though there have been investigations made on his petering-out, they haven't yielded anything conclusive as of yet.

Those who say Akhtar has 'burned out' since are just resorting to the familiar marketing-speak that people use when asked to describe someone who never tops his prodigious beginning. As if to suggest that his biggest demons have been acting distractions or the lack of hard work and discipline.

The truth, in this case, exists, somewhere outside such Dale Carnegie theories.

For my part, I think in his first film Farhan Akhtar was operating at the edge of his unconscious, putting out images and characters and colours and decors he knew were true, but ones whose truths he never cared to know too deeply about.

When I call Dil Chahta Hai a trivial masterpiece, I mean that as the ultimate compliment.

Because if it were anything more polished or worked out or homogenised, we would have got something of the order of the tone-deaf Lakshya, or the turgid films of Zoya Akhtar, or the campy yet self-conscious thereafters of Farhan Akhtar's own recent filmography.

There is a moment in the movie when the three men wax on about a ship that's moving, but very slowly -- the stillness of the imagery and how it will eventually get washed away.

The real sadness in that scene is the wishful thinking expressed that our high points can possibly be moored and held in place, rather than watch them bob along in the turning sea.

In Dil Chahta Hai, Farhan Akhtar was, to quote T S Eliot, trying to capture 'That still point of the turning world.' And he probably did it so quickly and intuitively, powered by an energy that flowed so naturally out of him, that he took home to his bed no specific lessons he could use later.

And by the time he had woken up, the world had turned. And the stillness was gone. And that ship had sailed out of focus, almost completely.

© 2024 Rediff.com -

© 2024 Rediff.com -