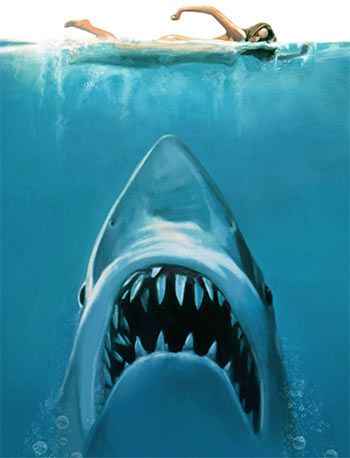

After all these years, Jaws still taps into nightmares, says Raja Sen.

One windy night 10 years ago, I was asked to write a horror movie.

As someone who is spooked far too easily, this was not, as one may imagine, an easy fit.

It was an intriguing challenge, though, and I began to watch every kind of fearful film -- from Korean to Kubrick -- in an attempt to try and understand the mechanics of the genre.

It is a fascinating, complicated genre. Because 'Boo' can be said with simplicity and with sophistication, with pant-wetting immediacy and with nightmare-inducing eerieness, and tremendous nuance is called for in the deployment of that weapon which, in my opinion, is the sharpest in the horror-filmmaker's arsenal, the False Scare.

The False Scare is what makes you sweat momentarily, just before it relents -- into daylight or laughter -- rendering the eventual moment of fear much more frightening, because of the building up of anticipation, sure, but more importantly because you have already been made aware of how much fear lies within you, how willing you are to be scared.

The Scare itself can be startling, gruesome, inventive, massive, but -- for me -- the False Scare is where the artistry lies.

I was still grappling with the structural requirements of the genre when the late Sourabh Usha Narang, one of my closest friends and the man who believed I should write movies, told me to stop enveloping myself in obscure horror cinema and watch one film that would make everything clear.

It did.

Jaws is a life-alteringly good film, the kind of film you can watch hundreds of times over and still marvel at how well the jigsaw fits, how watertight the structure is, how piano-wire-tight the tension stays, and how ominous that two-note theme tune remains, to this day.

Steven Spielberg was 26, and had just directed Sugarland Express, his debut feature film, when the Universal Pictures producers snapped him to direct Jaws, an adaptation of Peter Benchley's novel of the same name.

This was mostly because of the way Spielberg conjured up sheer dread in his 1971 television film, Duel, where a couple was terrorised by a sadistic truck driver. Based on a Richard Matheson film, Duel is a stunning film where Spielberg made a truck into a monster, painting it with sinister angles and sounds; giving that director a real creature-feature about a big shark was an obvious move.

But the film that came out of it wasn't obvious at all.

Jaws opens with thrill.

A seaside bash, some youthful revelry, from where emerges a young blonde girl who invitingly peels off her sweater and jumps naked into the water while her hastily-picked partner, too drunk to take his pants off quickly enough, watches her -- as we do -- cut through the water.

We see more of her, in fact, than he does, because of how Spielberg marinates his camera, constantly keeping it at or below sea-level. Almost one-fourth of Jaws is shot like this, literally immersing us in the water. And then there it is, the mercilessly sudden attack, the quickfire brutality, the shark we barely see but whose devastation is all-too apparent.

It's a stunningly effective sequence, one that hits us with all the possible horror while making it seem like the tip of the iceberg, and one whose effect lingers on in our heads as we watch the rest of this often slow-burning movie, making us jumpier than we normally would be.

Yet despite all the knuckle-whitening tension, Jaws is as impactful as it was four decades ago because of how strongly resonant its characters are, how they still ring true not just to story archetypes but to you and me and people we know, so to speak.

There's Chief Martin Brody, (Roy Scheider) the terse new police chief at Martha's Vineyard who admits to being scared of the water; there's Ellen, his wife, (Lorraine Gary) who is ever-so disappointed in her husband but not enough to do anything about it; there's Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) who rightfully thinks panic will drive customers away but entirely underestimates the threat at hand; there's Quint (Robert Shaw) the hard-drinking shanty-singing ol' sea dog who claims to know all; and there's Matt Hooper -- played by Richard Dreyfuss -- a nebbishy marine biologist who might look a bit like George Costanza but who, with his commonsensical and clever attitude, is clearly Spielberg's alter-ego on screen.

The writing sings.

A dry strain of humour slices through the proceedings, as men try to appear manlier by disguising their fear behind snark. With nerves increasingly frayed, the words get sharper and sharper and more aggressive until they can't get harsher anymore and finally -- with no more need for bravado -- we find three men in a boat singing and laughing and drinking about heartbreak, aware that each breath could well be their last.

With everyone out of their depth, we're all level.

With the measly special effects on hand in those days, Spielberg was forced to rethink his scenes, to shoot them without the shark because of how laughable it looked, and that fortuitously enough led to a Hitchcocking build-up of suspense that tightens and tightens and tightens till the audience squirms.

Spielberg had once boasted about how he wanted, in Jaws, three moments of popcorn flying in front the screen because of sheer shock, and I'm surprised to say that watching the familiar film again a few days ago, well aware of the scares in store for me, one of those moments -- involving a certain head -- got me, and got me good. I yelped.

After all these years, Jaws still taps into the nightmares. And that's not just Moby Dicking around.

A couple of years ago, when I had the chance to ask the great director something, it had to be about Jaws, and hubris.

He laughed it off warmly and candidly, but part of him seemed still wistful that Jaws -- the greatest blockbuster of them all, the film that birthed the very concept of the summer release -- could have gotten more respect back in the day.

Forty years on, it has everything it deserves: It is a film that has outlasted most of its contemporaries, a film that remains influential, integral and vibrant, and a film that -- when studied -- is a masterclass in horror.

There is no bigger boat.

© 2025

© 2025