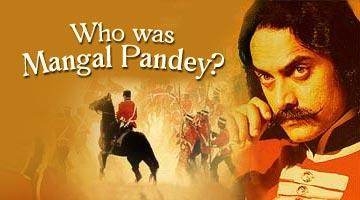

For the few who think of Mangal Pandey as just another character role played by Aamir Khan, a quick lesson in history:

So, he's not a fictional character?

Of course not. Born in the village of Nagwa, district Ballia, Uttar Pradesh, Mangal Pandey was introduced to history books as the sepoy who played a major role in the Indian uprising of 1857.

He was a soldier of the 34th Native Infantry whose attack on a superior officer came to be recognised as the event that sparked India's First War of Independence. Little is known of his life before that momentous incident but he has been declared a martyr since.

Special: Showcasing Mangal Pandey

What happened that day?

Pandey attacked his British sergeant and wounded an adjutant. The office in charge, General Hearsay, noticed that Pandey was in the throes of some sort of 'religious frenzy', and ordered a jamadaar to arrest him. The latter refused.

Surrounded by guards and European officers, Pandey tried to commit suicide by shooting himself. He was seriously wounded, and promptly arrested.

Following a court-martial on April 6, he was hanged at Barrackpore on April 8, 1857. As a collective punishment for his act, the entire regiment was also dismissed.

Was he India's first freedom fighter?

According to records at the Jabalpur Museum, Pandey was to be executed on April 18. But he was hanged 10 days earlier to prevent the regiment from harbouring ill will against superiors. The English were also aware that news of Pandey's death could spark more unrest.

Going by the date on which he was executed, Mangal Pandey became the first freedom fighter and martyr of 1857.

His name has since been synonymous with revolt.

Has Pandey been in the news before?

Yes. He made an appearance in newspapers not so long ago, with the release of Mangal Pandey: Brave Martyr or Accidental Hero?, a book by Rudranghsu Mukherjee.

The author claimed Pandey was an ordinary sepoy who, under the influence of bhang,

The book had its share of controversial statements such as: 'Nationalism creates its own myths. Mangal Pandey is part of that imagination of historians. He had no notion of patriotism or even of India. For him, mulk was a small village, Awadh.'

It also went on to claim that Pandey's action was contrary to the spirit of insurgency: 'A rebellion is a collective will to overthrow an oppressive order. Pandey acted alone; he was a rebel without a rebellion. The name Mangal Pandey meant nothing to the sepoys who raised the revolt in 1857.' Luckily for us, no post-publication riots ensued.

Does he ever appear outside history books?

You might want to try the post office. The Indian Posts and Telegraphs Department has issued four commemorative stamps in the memory of freedom fighters, one of which sports the face of Mangal Pandey. Interestingly, British author Zadie Smith's award-winning novel White Teeth also has a reference, with Pandey cast as the fictional protagonist Samad's great grandfather.

Why did Mangal Pandey do what he did?

There are a number of reasons. To understand his action, one must analyse the religious, social and political milieu in which he operated. In a nutshell, the British already had given the Indians much cause for unhappiness, thanks to the doctrine of Lapse, the forcible introduction of a British system of education, and social reforms that didn't exactly go down well with the higher castes. The sepoys were also dissatisfied with army life. Coupled with low pay, their need to constantly pit themselves against their countrymen also took its toll.

To make things worse, the East India Company introduced the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle. Its cartridges were covered by greased membrane that, apparently, had to be cut by the teeth before loading. There was a rumour that this membrane was greased by cow or pig fat, which was offensive to Hindu as well as Muslim soldiers.

The British tried reasoning with the sepoys, and even asked them to make their own grease from vegetable oils. The rumour, however, persisted. General George Anson, Commander in Chief in India, reacted by saying, 'I'll never give in to their beastly prejudices.' He refused to compromise.

Then, on March 29, 1857, at Barrackpore near Kolkata, Mangal Pandey started an open mutiny, inviting his comrades to join him.

The Rising had begun.