The Centre needs to have dialogue with the Opposition instead of letting politics come in the way; it needs to stoop to conquer, says Aditi Phadnis.

Will the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government now use the Money Bill route to get Parliament - more to the point the Rajya Sabha where it does not have a majority - to clear legislation?

The fact is, getting all Bills to be classified as Money Bill to circumvent the Rajya Sabha could be a stretch.

Under Article 110(1) of the Constitution, a Bill is deemed to be a Money Bill if it contains only provisions dealing with all or any of the following matters, namely:

(a) the imposition, abolition, remission, alteration or regulation of any tax;

(b) the regulation of the borrowing of money or the giving of any guarantee by the Government of India, or the amendment of the law with respect to any financial obligations undertaken or to be undertaken by the Government of India;

(c) the custody of the Consolidated Fund or the Contingency Fund of India, the payment of moneys into or the withdrawal of moneys from any such fund;

(d) the appropriation of moneys out of the Consolidated Fund of India;

(e) the declaring of any expenditure to be expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India or the increasing of the amount of any such expenditure;

(f) the receipt of money on account of the Consolidated Fund of India or the public account of India or the custody or issue of such money or the audit of the accounts of the Union or of a State; or

(g) any matter incidental to any of the matters specified in sub-clauses (a) to (f).

A Bill is not deemed to be Money Bill by reason only that it provides for the imposition of fines or other pecuniary penalties, or for the demand or payment of fees for licences or fees for services rendered, or by reason that it provides for the imposition, abolition, remission, alteration or regulation of any tax by any local authority or body for local purposes.

The term “incidental” in article 110(1) (g) of the Constitution has wide implications. It is comprehensive enough to include not merely the rates, area and field of tax, but also complete machinery for assessment, appeals, revisions, etc. It is in this light that Finance Bill which, in addition to rates of taxation, contain provisions regarding machinery for collection, etc. are certified as Money Bill.

Similarly, a Bill seeking to amend or consolidate the law relating to Income-tax is treated as a Money Bill. Since such bills substantially aim at imposition, abolition, etc. of any tax, the presence of other incidental provisions do not take them out of the category of Money Bill. Thus there may be only one section in a Money Bill imposing a tax and there may be several other sections which may deal with the scope, method, manner, etc. of its imposition.

Certification of Money Bill

A Money Bill can be introduced in Lok Sabha only.

If any question arises whether a Bill is a Money Bill or not, the decision of Speaker thereon is final. The Speaker is under no obligation to consult any one in coming to a decision or in giving his certificate that a Bill is a Money Bill. The certificate of the Speaker to the effect that a Bill is a Money Bill, is to be endorsed and signed by him when it is transmitted to Rajya Sabha and also when it is presented to the President for his assent.

The Speaker’s certificate on a Money Bill once given is final and cannot be challenged.

A Money Bill cannot be referred to a Joint Committee of the Houses.

Constitution Amendment Bills - not treated as Money Bill

A Constitution Amendment Bill is not treated as a Money Bill even if all its provisions attract article 110(1) for the reason that such amendments are governed by article 368 which over-rides the provisions regarding Money Bills.

Rajya Sabha is required to return a Money Bill passed and transmitted by Lok Sabha within a period of fourteen days from the date of its receipt. The period of fourteen days is computed from the date of receipt of the Bill in the Rajya Sabha Secretariat and not from the date on which it is laid on the table of Rajya Sabha.

14. Rajya Sabha may return a Money Bill transmitted to it with or without its recommendations.

15. If a Money Bill is returned by Rajya Sabha without any recommendation, it is presented to the President for his assent.

16. If a Money Bill is returned by Rajya Sabha with recommendations, it is laid on the Table of Lok Sabha and Lok Sabha has to clear it within two days, after voting on the recommendations. If Lok Sabha accepts the amendment recommended by Rajya Sabha, the Money Bill is deemed to have been passed by both Houses of Parliament with the amendments recommended by Rajya Sabha and accepted by Lok Sabha.

If Lok Sabha does not accept any of the amendments recommended by Rajya Sabha, the Money Bill is deemed to have been passed by both the Houses of Parliament in the form in which it was passed by Lok Sabha, without any of the amendments recommended by Rajya Sabha and it is presented to the President for his assent.

However, if Rajya Sabha does not return a Money Bill within the prescribed period of fourteen days, the Bill is deemed to have been passed by both Houses of Parliament at the end of the 14 days.

Under the Constitution, a Money Bill cannot be returned to the House by the President for reconsideration.

Against this background, theoretically, armed with the assent of the Speaker (who, as CPI M MP Sitaram Yechury pointed out is appointed following a recommendation by the government in power) any Bill can be certified by the Speaker as a money Bill.

However, in the future, this could cause a dangerous precedent to be laid.

All parties have resorted to this route to get Bills passed through a House where they have not had a majority. Rajiv Gandhi used this to get the Juvenile Justice Bill passed, despite a brute majority of 400-plus MPs in Lok Sabha.

On the other hand, persuasion and ultimately consensus on thorny issues can also be a way to pilot legislation. Take the case of the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Bill 2015, for instance. This was initially an ordinance and which several parties said they would oppose for procedural reasons.

But the very same NDA government managed to get both Houses to clear the Bill by breaking opposition unity with parties like Trinamool Congress, Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party and Nationalist Congress Party, which made common cause with Congress and other parties and complained to the President.

A party like Biju Janata Dal in speeches it made opposed various provisions of the Bill but voted for it after it was persuaded that it would be in its interest. "All our concerns in the Bill have been addressed and we have clearly indicated to the government that we will vote with them," Trinamool Congress member Derek O'Brien said. There is no party more opposed to the BJP than Trinamool Congress.

The short point is that the government needs to dialogue with the opposition instead of letting politics come in the way. In this respect, it needs to stoop to conquer. Taking recourse to other measures – like classifying Bills that are patently not money bills as such – will distort parliamentary practice and could come back to bite India in the leg.

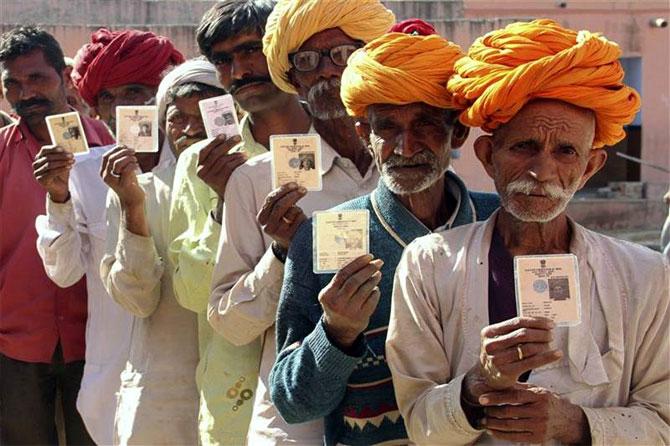

Photograph, courtesy: UIDAI